- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

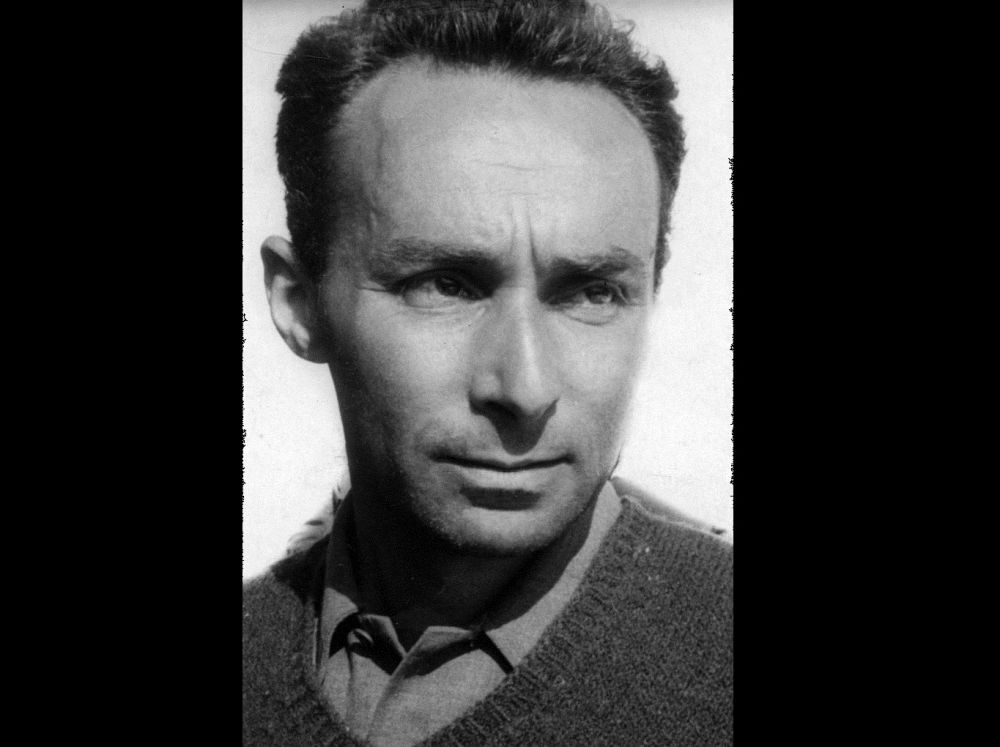

Primo Levi, 1950s / Wikipedia, public domain

Scrittore d’occasione, an occasional writer. That’s how he called himself.

Were it not for his deportation to Auschwitz together with a partisan group (he was active in the antifascist resistance movement), his imprisonment at the camp and survival thanks to his profession (a chemist), we wouldn’t have heard of the writer’s talent and of his intellectual attempts to cope with experiencing the Holocaust.

In a short preface to his most famous book, If this is a man (Se questo un uomo, 1947), he wrote mainly about an attempt to achieve a state ot "inner liberation" and providing "documents for the purpose of calm studying of certain aspects of human attitudes".

The record of shocking personal accounts is a chilling analysis of the evil of Auschwitz, a journey through hell without Dante’s immunity, leading to the destructive act of discovery and a conclusion that one cannot witness the horror without cosequences. An individual impacted by such a discovery is bound to lose themselves and their world forever. Levi claims that there’s no return for those who had survived the camp.

"We won’t come back", writes Levi, after the "process of bestialization" and discovering "what one man was able to do to another".

After sixteen years or silence, he published The Truce (La tregua, 1963). The mini-odyssey on the Auschwitz-Turin route presents the author’s return home, in a literal and metaphorical sense, and his way of coping with extreme experiences. This, time, home, family, the lush land of Piemonte and sensual nature become an answer to the evil of the Holocaust. The peaceful rest turns out to be temporary, because "beyond the Lager, nothing was the truth".

After writing his books-testimonies and earlier declarations about putting his pen away and returning to his work in chemistry, Primo Levi was unable to give up writing completely. He keeps publishing poetry and short stories. Towards the end of his lifetime, he said about himself: "whilst being a chemist for the eye of the world, but with the blood of a writer in my veins, I had an impressions as if I had two souls, one too many".

These shocks which had been affecting his writer’s soul led to publishing phenomenal poetry. Prose – with its dramatic existential parabola (wartime experiences and the suffering in the concentration camp) turned out to be insufficient for a full self-expression. Primo himself explained this again, this time as a poet:

"I am a human being. I as well, in irregular periods, at an uncertain hour, have been prone to an impulse which is said to be encoded in our genetic legacy. Poetry seemed to be more accurate than prose to express a certain thought or image. I cannot say why."

"My natural state is not to write poetry; yet from time to time, this strange infection visits me, like an exciting, contagious disease."

It remains uncertain whether the writer committed suicide, or if a fall from stairs, which eventually led to his death, was an accident. His life ended on 11 April 1987, forty years after his return from Auschwitz.

The readers have been left with subtle descriptions of shame caused by a sense humiliation which kept following liberated prisoners of the concentration camps, a sense of an absurd injustice that the highest evil in the world is absolutely possible. Primo Levi’s world, skewed with an ironic sense or humor, has (prophetically) brought a new type of a protagonist, who – instead of a tattoo with the prisoner’s number – carries a tattoo with advertising slogans.

Agave

I am neither useful nor beautiful,

I don’t have calming colours or scents,

My roots can break cement,

while my spiky leaves

guard me like sharp swords.

I am silent. I can speak only with my plant language,

difficult to understand for you, human being.

It’s an unfashionable language,

exotic, as I come from far away,

from a cruel land,

full of wind, poison and volcanoes.

I have been waiting for years,

Until I bore my flower, sharp and desperate,

Ugly, fibrous, stiff, but pointing towards the sky.

This is the way in which we announce

that tomorrow I’ll die. Can you understand me now?

10.09.1983

(Primo Levi, Ocalały. Wybór wierszy, transl. by Jarosław Mikołajewski, 2014, Austeria Publishing House)

translated by Olga Drenda

Read also: Liberation of Auschwitz in the eyes of Primo Levi