- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

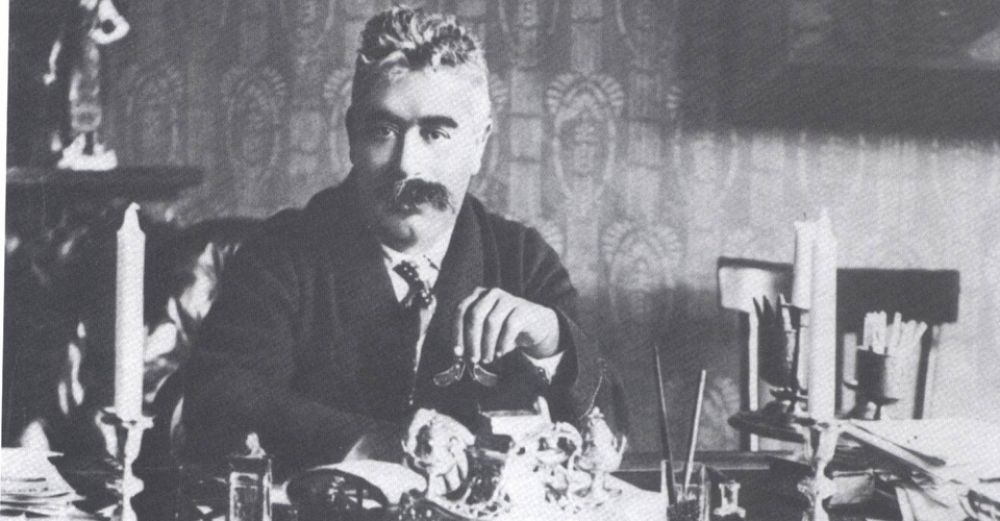

Yitshkok Leybush Peretz was born on 18 May 1852 in Zamość, as the second child of Yehuda Peretz (1825–1898), a merchant, and Rivke nee Lewin (1828–1914). They had many children, but most of them hadn’t survived until adulthood. Father moved to Zamość from Lubartów. For many years, he was trading wood, sent to Gdańsk down the Vistula river. The writer remembered him as a liberal, even an anarchist. Due to Peretz’s work in trade, the family maintained contact with the non-Jewish world. The writer’s family home was deeply religious, but with a certain cosmopolitan atmosphere, with portraits of Napoleon III and his wife empress Eugenia on the walls.

According to the custom of the time, Peretz received traditional religious education. As a student, he was rebellious, but very talented, with a genius potential – he began to study the Torah at the age of 3, and the Gemara – at the age of 7. While studying in yeshivas in Zamość and Szczebrzeszyn (he probably hadn’t completed his education in either of them), he discovered the works of Maimonides and the kabbalists. When he grew up, he began to learn Russian and German from private tutors. His father, who appreciated the significance of secular education, wanted to send his son to gymnasium, but the pious mother eventually disagreed.

Peretz spend his youth mostly on intensive secular self-education. He was reading a lot, mostly in Polish; his favourite subjects were sciences, modern concepts, discoveries and inventions, but at the same time, he began to fall in love with literature. His greatest fascination was Heinrich Heine. Probably it was the moment in which he discovered his own literary interests. In 1874, while spending summer in Grabów, in the manor belonging to his Polonised family, the Altbergs, he wrote his first poems in Polish. The choice of language wasn’t accidental – since the national uprising in 1863, Peretz declared himself as a Polish patriot. In Maine zichroines, he wrote: „We were dedicated Poles! We prayed long for success of the second uprising”. In the following years, anti-Semitism painfully challenged his patriotic feelings.

In 1870, Peretz married Sara, a daughter of a famous and rich maskil Gabriel Jehuda Lichtenfeld (1811–1887). The couple moved to Opatów, later to Sandomierz. Peretz wasn’t successful with his business; he lost his distillery. At the same time, he experienced a deep crisis of faith. He gave up on his lifestyle and way of dressing, he also burned his pious wife’s wig in a furnace. Their marriage collapsed after five years.

He spent 1876 and 1877 in Warsaw, giving private Hebrew lessons for living. His ex-father-in-law encouraged him to write in Hebrew. In 1877, he published his first volume of poems in this language, Sipurim beszir. His debut was welcomed by critics, but soon he had to deal with a disappointment. Unable to support himself with royalties for works published in the Hebrew press, Peretz gave up writing and returned to Zamość.

In 1878, he married Helen (Nacham Rachel) Ringelhejm (1857–1938), an educated, well-read young woman from a wealthy merchant family in Łęczna. He tried to open a private Hebrew school in Zamość, but local orthodoxes opposed this. For a certain period of time, he co-owned a mill. In 1876, he passed a law exam at the Regional Court in Warsaw and opened a private practice in his home town. His clients were Jews, Poles and Russians. For the following ten years, he enjoyed a relatively prosperous and peaceful life, at the same time engaging himself in philanthropy and social activism.

In 1887, following an anynymous denunciation, Peretz was accused of spreading subversive ideas and lost the right to work as a lawyer. Desperately looking for other sources of income, he returned to intensive writing. One year later, in a literary almanac Di judisze folks-bibliotek (Jewish Folk Library), edited by Sholem Aleichem, he published his first Yiddish-language work, the ballad Monisz. The critical reception was negative. Only Jankew Dinezon realized the greatness of the author from Zamość. Both writers later became good friends for years.

When Peretz moved to Warsaw for good in 1889, his financial situation was still very bad. Help came from a philanthropist and social activist Jan Bloch. In 1890, Peretz joined Bloch’s statistical expedition, researching the situation of Jews in small towns. He visited Tyszowce, Jarczów, Łaszczów, Tomaszów Lubelski and other places. During his travels, he wrote a series of fictionalized accounts, published in 1891 as Bil — der fun a prowinc-rajze in tomaszower powiat um 1890 jor (Images from travels through the Tomaszów province about 1890).

In 1891, he became an employee of the Funeral Department of the Jewish community of Warsaw. His duties involved allocation of graves at the Warsaw cemetery at Gęsia street (today at the junction of Mordechaja Anielewicza and Okopowa streets).

Peretz’s life was running on two parallel tracks, as if he had two lives. In one of them, he was a local official, in the other one, a writer. His duties related to writing consumed enormous amounts of time and energy. The Yiddish culture didn’t yet have its own institutions, or developed market of press and books. Peretz had to build it all from scratch. He gave lectures, worked as a promoter, critic, columnist, launched new magazines. He published several literary almanacs: Di judisze blibliotek (The Jewish library, 1891–1895), Ha-chec (The arrow, 1894), Literatur un lebn (Literature and life, 1895) and a series of irregularly published periodicals Jontew bletlech (Festive gazettes, 1894–1896), where, aside from prose, he published articles dedicated to economics, politics or biology in Yiddish, which was a pioneering move. His efforts and hard work were crowned with a conference in Chernivtsi in 1908, where Yiddish was announced a Jewish national language.

Even though he had to constantly take breaks in his creative work, he remained prolific, writing poems, prose and dramas. Between 1909 and 1913, the first complete edition of his works in Yiddish was published. Folkstimleche geszichtn (Folk stories, 1904) and drama Di goldene kejt (The golden chain, 1909) brought him the biggest fame. His work was innovative and new in his time. It evaded classifications in one category, remaining distinguished by „a provocative mixing of the old and the new, which makes the strange familiar, and the familiar strange”. The writer merged tradition and modernity, religiousness and secular approach, Jewishness and Europeanness.

Peretz was also engages in politics and social issues. He was writing about Tsarist anti-Jewish policy, attacking supporters of assimilation, defending women’s rights. In 1899, during an illegal rally for striking workers, he was arrested for several months in Tsarist political prison in the Warsaw Citadel. In 1912, Peretz became conflicted with the community leaders, who demanded of him withdrawing from political activity. As a sign of protest, the writer published a declaration that he signed a work contract, not a contract regarding his conscience.

Peretz’s name became famous in the Jewish world. He attracted crowds of young writers from Central and Eastern Europe to Warsaw. He supported talents and introduced them into the art of writing. Among the graduates of his school of literature, we can find a whole array of younger generation writers: Szalom Asz, Josef Opatoszu, Dowid Bergelson, Bal Machszowes, Icze Meir Weissenberg, Jankew Jeszaja Trunk, Jehojesz (Salomon Blumgarten), Efraim Kaganowski, Der Nister (Pinchas Kaganowicz), Awrom Rejzen, Hirsz Nomberg, Lamed Szapiro, Alter Kacyzne.

While Peretz felt accomplished as a father of a great literary family, his personal life suffered. His relationship with Lucjan, his only son from his first marriage (the second son, Jankew, died at a young age), wasn’t marked by conflict, caused probably by the son’s trauma due to alienation from his mother after his parents’ divorce. Additionally, the conflict was deepened by Lucjan’s disapproval of everything Jewish. He brought up his son Janek away from his forefathers’ traditions and culture. In his adulthood, Peretz’s grandson left the Jewish community, breaking ties with his origins.

When the World War I broke out, Peretz dedicated himself to charity. He was actively engaged in aid work for the homeless and the hungry. Along with Dinezon, he was opening first shelters and schools for orphaned and abandoned Jewish children. With his youngest students in mind, he was writing poems, lullabies and short stories. Additionally, he was working on his translation of the Torah to Yiddish.

The writer’s body, once strong, eventually didn’t survive the irregularity of life, intensive, exhausting work, stress related to war experiences. On 3 April, in late afternoon, he died of heart attack. From that moment on, the history of Jewish literature became divided into two eras: before Peretz and after.