- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

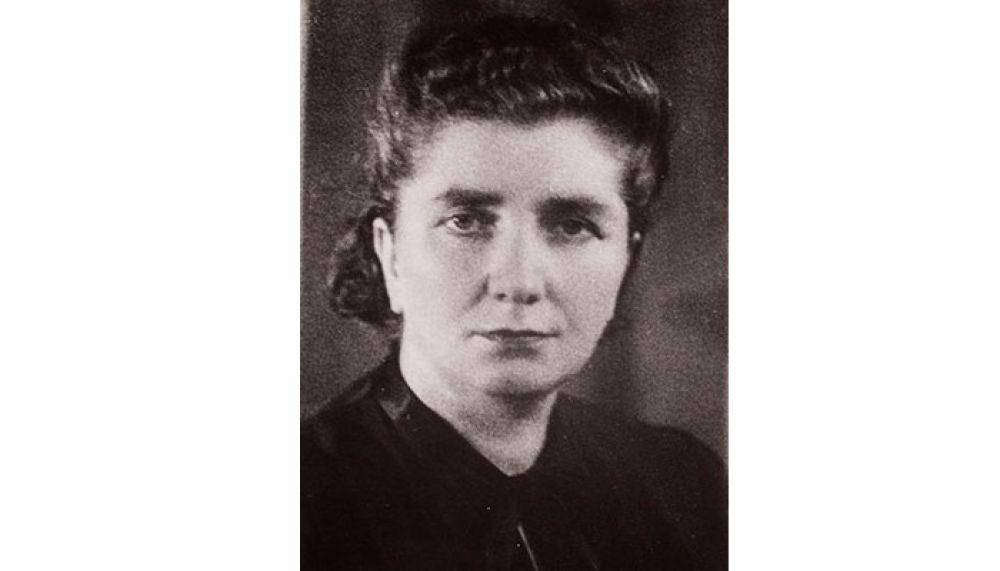

Even before the war, Rachel Auerbach’s life was not easy. In her youth, she experienced all the worries of a young Jewish writer. Due to financial problems, she could not finish her studies. She also had a toxic relationship with her husband, an outstanding Yiddish poet, Itzik Manger. Her professional work overshadowed her literary activities, and her initiatives to promote the Yiddish language were also unsuccessful.

After the outbreak of the war, Auerbach decided to stay in Warsaw. She found herself in the ghetto established by the Germans in the fall of 1940. In 1941, she was recruited to the Oneg Shabbat group. Her writings – including a journal commissioned by Emanuel Ringelblum and written from August 1941 to July 1942 – are among the most valuable collections kept in the Ringelblum Archive. They are distinguished not only by documentary but also literary value.

The scene at the exit of Mylna Street – dozens of such scenes are seen every day. A lady left the grocery store with a purse full of some small supplies. The “catcher” lurking in front of the door – not even one of the most juvenile ones – grabbed the package with both hands, reached inside and started packing it in his mouth with lightning speed. This is the main tactic of the catchers. (…)

The catcher does not take what is not food. He will never be interested in a women’s handbag sticking out from under the arm. Once a rascal snatched a packet of shoe polish from me, I screamed what it was and he gave it back to me (already, he almost sank his teeth into it). A comical thing was noticed a few days ago by a clerk I know. A catcher grabbed a package containing 2 kilograms of meat. Several people started chasing him. After a while, after knowing the contents of the package, he tossed it back. “Ch ‘hob gemejnt s’iz brojt [I thought it was bread],” he said. So it is not about the monetary value of the bag. It is about its immediate edibility. Nevertheless, people say there is a fencing shop in Nowolipie Street, which buys uneaten bread from catchers. (…)

In the pantheon of martyrs and heroes of our present, darkest times, a prominent place should be found for the Jewish and Polish smuggler who, for economic reasons or for the sustaining of personal existence, for a piece of bread or a bowl of potatoes – all this is true – is, however, the most fearless and persistent one, he is the most active fighter in the unequal fight that the city, tied for […], is waging against brutal, murderous violence. Honor to the unknown smuggler, the gray soldier on the walls of a closed city.

– Auerbach wrote on June 6, 1942.

Before the second part of the Archive was found, in 1950 Auerbach left for Israel. In the spring of 1954, she started working at the Yad Vashem Institute. She created a testimonials section there, “she dealt with both the theory, methodology and practice of collecting reports. For example, she believed that witness testimonies should be recorded, because writing interrupts the narrative process, reduces its tension, and the written account does not always reflect the features of the witness’s language, the way they formulate thoughts, the work of memory” – writes Karolina Szymaniak. It was an innovative approach back then: it was only in the following decades that the importance of the recordings of the witnesses of the Holocaust was appreciated.

In 1961, Auerbach took part in the preparation of documentation for the trial of Adolf Eichmann. She also testified herself: “she asked for an hour and a half, she was given forty-five minutes, and interrogations were still a quarter shorter”. She testified after Yitzhak Zuckerman and Zivia Lubetkin; “she was so upset that she was not able to testify well, and was also disciplined by the court and the prosecutor.”

After her retirement, Auerbach continued to work on her own books. In 1974, she published in Yiddish the book Warsaw testaments. Meetings, activities, fates 1933-1943. “Another book, which she wrote and dictated already seriously ill, lying in bed, she did not manage to finish.” She died of cancer. The book On the last way. In the Warsaw ghetto and on the ‘Aryan’ side was published after her death.