- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Cecylia Słapakowa was born around 1900 in Vilnius, in a family of Russian-speaking Jews.

She belonged to the circle of the Russian and Yiddish-speaking Jewish intellectual elite of Vilnius and Riga, as well as Polish and Yiddish-speaking Jewish intelligentsia of Warsaw. She lived together with her family on the ground floor of 1 Elektoralna street. Before the war broke out, she married a film production engineer and gave birth to a daughter.

She published in „Nasz Przegląd”, a daily newspaper popular among Jewish intelligentsia and bourgeoisie, she also cooperated with the Warsaw subsidiary of YIVO Institute. Slapakowa was also a translator – for example, she translated the 12-volume Jewish History by Simon Dubnow from Russian to Polish.

In her house at 1 Elektoralna street, she created a literary salon, which continued to exist during the war. She remained in close contact with renowned Yiddish-language critic Szmul Niger and his brother Daniel Czarny, as well as with Marc and Bella Chagall. [1] According to Rachela Auerbach, she was inviting Jewish intellectuals, artists and writers in order to fight overwhelming fear and depression. Her teas resembled a pre-war salon, where conversation and a humble meal helped forget about the war at least for a few hours. Sometimes, the guests themselves offered to play music. [2] She had to give it up after moving to the ghetto.

We have little information about Słapakowa’s life in the ghetto. We know for certain that she was cooperating with the Oneg Shabbat group. In the Archive, she left 17 interviews with Jewish women from various social backgrounds and professions, conducted in the ghetto in the Spring of 1942. Słapakowa probably passed her notebooks to Eliasz Gutkowski or Hersz Wasser before the beginning of the Great Deportation on 22 July 1942 and 4 August, when the first part of the Archive was hidden. [3]

Cecylia Słapakowa died together with her daughter probably during the first deportation in the Summer of 1942. According to Rachela Auerbach, Słapakowa’s husband had survived the war.

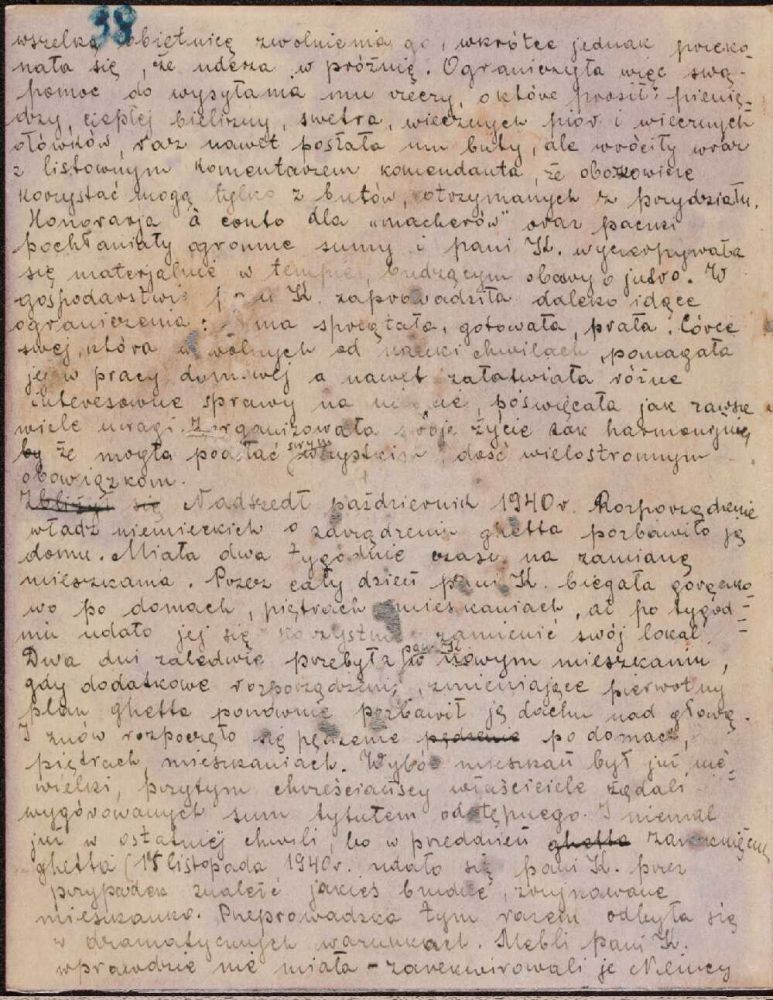

![słapakowa_2_Konspekt_Ringelblum.jpg [121.45 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/80d7408330290914470122837cee0729/jpg/jhi/preview/słapakowa_2_Konspekt_Ringelblum.jpg)

Report: „The Jewish woman in Warsaw from September 1939 until now [1942]”

Interviews conducted by Słapakowa are one of the most important sources for research of the life in the Warsaw Ghetto – they present a shift in the social role of women during the war, but they also praise their versatility, courage and sacrifice.

According to dr Katarzyna Person, Cecylia describes their life from the beginning of the war with great empathy. She doesn’t judge her protagonists. She shows that every method of survival in the ghetto is acceptable (…) Women face the life in the ghetto, and she sees a value in that (…) It is interesting that in stories written down by Cecylia, men appear in the background, practically always as weak. They lose jobs, get ill, become depressed. Evidently, in the ghetto, the roles are switched – women take the initiative. [4]

Słapakowa was asking her interlocutors in detail about their lives before the war, during the siege, and in the current moment, about their ways of surviving after the ghetto was established. They’re divided by many factors – origins, education, age, profession, but they also share a lot: wartime experiences, hard work in order to support themselves and their families in worsening ghetto conditions (leaving the house early, returning after the police curfew), and belief that they will manage to make it through the war.

![słapakowa_3_mieszkanka-getta.jpg [509.80 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/e92ad04012c19f77e79d5ec7d943aea4/jpg/jhi/preview/słapakowa_3_mieszkanka-getta.jpg)

Mrs F. Got used to sharp zig-zags in her daily existence with a kind of fatalistic acceptance. She developed a philosophical approach to life, typical for many Jewish women today. She claims: „Everything I have to bear is necessary evil. I have to survive. After the war, I will make up for my losses”. Mrs F. faces all the adversities standing in the way of her survival with courage. [5]

Mrs D. is silent. Her pale face suddenly becomes excited. She stands half inclined, washing the top of the cupboard rhytmically. Suddenly, she stands up, turns towards the „Madam” and shouts out: „Madam, I want to survive this was so much”! [6]

She spoke, among others, with a corset-maker turned smuggler (she gave up, because, as she says, life is the most important thing. I used to risk for life, what a nonsense to risk something for death [7]), daughter of a restaurant owner who worked as a prostitute in an entertainment club, a philologist who spoke four languages and worked in a box factory, librarian (who, as the only one, can be identified – it’s Basia Temkin-Berman, the only interviewed woman certainly known to have survived), a refugee, a cleaner; she described the struggle of a mother of four, sentenced to death for smuggling.

![słapakowa_4_ARG-I-683-14_2.jpg [45.99 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/fb5d5b9de195e9336d24576f95cfa39c/jpg/jhi/preview/słapakowa_4_ARG-I-683-14_2.jpg)

Women are eating bread / The Ringelblum Archive

Admiration for these women is visible in every sentence. She writes: It seems certain and beyond any doubt that the current war has predestined the Jewish woman to become a winner of life. [8] Słapakowa described situations which show that the war paradoxically made some of them reach the heights of their destiny. [9] She writes about a nurse who managed the kitchen for orphans (Mrs B. finds an outlet for her energy in social work, and results she achievesgive her satisfaction and reinforce her in her fight for survival [10]), Mrs G., whose life before the war was careless and idle, but in the ghetto, she showed altruism and helped others; or about the manager of the instructors of social kitchens, who reorganized and improved the nutrition system. Słapakowa noted that their will for life not only doesn’t wane in the face of adversity, but quite the contrary, explodes with a defensive reaction. They keep fighting, because their will for life prevails. [11]

Miss B. became absorbed by her work with passion and reinforced awareness of the significance and necessity of her job. It is her psychological outlet, and her good condition allows her to deal better than other women with the difficulties of her material situation and changes due to loss of her flat because of the ghetto. When Miss B. comes back home, she has to take care of the house: she cooks, washes, cleans on her own. She lives in a room, as a tenant, which can be a difficult experience sometimes. But Miss B. slides over this, armored with an awareness that she has a job in which she found herself, and which made her contribute to the society. [12]

The worse her situation was, the more energy she was putting in overcoming evil. [13]

Słapakowa’s interviews were in line with YIVO’s tradition of „researching the present” in order to change the future. Perhaps Słapakowa believed that her research will prompt others to rethink social attitudes after the war. [14]

The goal: „to survive” doesn’t limit the ambitions of the Jewish woman. She wants to build foundations for future social and economic rebirth. Hence, the rush towards work. In this field, the achievements of the Jewish women are remarkable. [15]

Słapakowa wascertainly aware that it was diificult, if not impossible, to present an objective judgement of the role of Jewish women during the war. Yet she believed that direct observations allow for general conclusions, such as the one that Jewish women have an ability to adjust to sudden changes in their situation [16], that they have been active in nearly all fields of life, and in some of them, they achieved hegemony over men, becoming a constructing factor or our new economic and moral reality [17], they contributed a refreshing trust and courage, freshness of intention, content of ideas, humanitarianism; that they don’t give up easily, start again, try new ways, and one of their most important motivations is necessity, for the sake of which they can even sacrifice their own downfall – which proves only their heroism, not weakness. [18]

All the interviews are available in Volume 5 of the Ringelblum Archive: Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne (only in Polish), ed. by Katarzyna Person.

Written by: Anna Majchrowska

Translated by: Olga Drenda

![słapakowa_5_JOST-040_1.jpg [95.21 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/53e0dc4c61edbe04d1fea0a85622c94b/jpg/jhi/preview/słapakowa_5_JOST-040_1.jpg)

Heinrich Jost / Nowolipki street, the corner of Karmelicka Street /

A woman with swollen legs holds a child in her arms / 19 September 1941/ JHI Collection

Footnotes:

[1] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017, p. 315.

[2] Ibidem.

[3] Ibidem, p. 420

[4] http://www.wysokieobcasy.pl/wysokie-obcasy/7,127763,23071460,archiwum-ringelbluma-gela-gustawa-rachela-cecylia-zydowki-z.html

[5] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Tom 5, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, opr. Katarzyna Person, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2011, p. 211.

[6] Ibidem, p. 260.

[7] Ibidem, p.202.

[8]Ibidem, p. 195.

[9] Ibidem, p. 238.

[10] Ibidem, p. 222.

[11] Ibidem.

[12] Ibidem, p. 239.

[13] Ibidem, p. 227.

[14] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, op. cit., p. 428.

[15] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Tom 5, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, op. cit., p. 195.

[16] Ibidem.

[17] Ibidem.

[18] Ibidem, p. 195-196

Bibliography:

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Vol. 5, Getto warszawskie. Życie codzienne, opr. Katarzyna Person, ŻIH, Warszawa 2011.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017.