- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

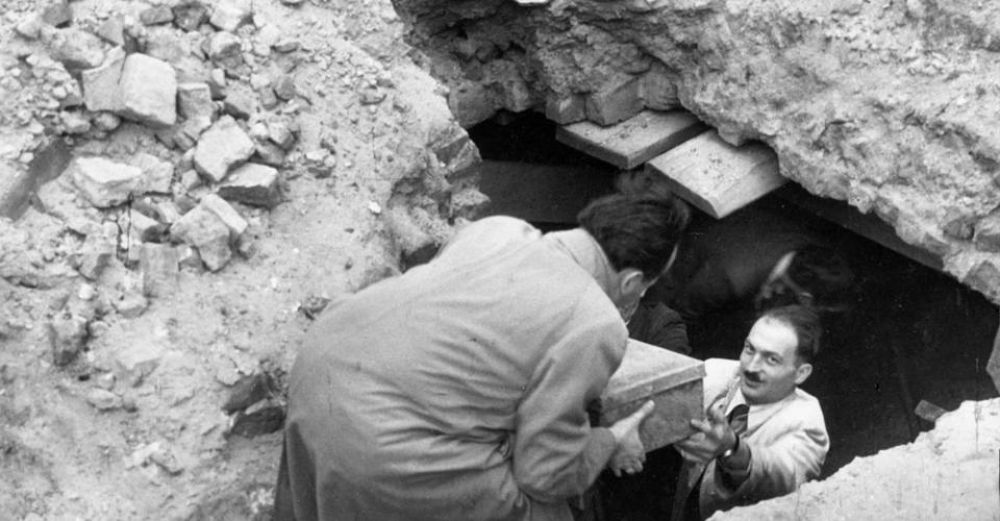

Unearthing of the first part of the Ringelblum Archive. In the picture: Michał Borwicz and Hersz Wasser /

Izrael Lichtensztajn, Emanuel Ringelblum’s close associate, worked at the Ber Borochov school at 68 Nowolipki street. Together with Dawid Graber and Nachum Grzywacz, students who were privy to Oneg Shabbat’s secret works – he was responsible for gathering and securing the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto, and eventually – for hiding it in the basement of the school.

According to Dawid Graber’s account, the documentation had been collected at the Borochov school since late 1941-early 1942, when information about the destruction of the Jewish Scientific Institute (YIVO) in Vilnius arrived in Warsaw. According to A. Bańkowska and A. Haska, hiding the first part of the Archive in metal boxes (15 x 30 x 50 cm) mst have taken several days, as proven by excerpts from Abraham Lewin’s diaries and Izrael Lichtensztajn and Gela Seksztajn testaments. [1] The last part of the documents was buried on 3 August 1942 at 4 PM, which we know from Dawid Graber’s testament. People who certainly knew about the location of the documents were Hersz Wasser and Emanuel Ringelblum, who postulated to pass the address to YIVO and Rafał Mahler in New York.

After the Great Deportation, communication between the surviving members of Oneg Shabbat became more difficult, hence the circumstances and time of hiding the second part of the materials remain unknown. Because the latest document from the second part of the Archive is an issue of the „Biuletyn Informacyjny Żagiew” periodical from 1 February 1943, it is assumed that it must have been February 1943 [3]. Soon, Rachela Auerbach and Emanuel Ringelblum had left the Ghetto, and the only Oneg Shabbat members who remained inside were: Hersz Wasser, Eliasz Gutkowski, Izrael Lichtensztejn, Menachem Kohn and Szmuel Winter. [4] According to Wasser, the group had been active until April 1943, still collecting documents. There is a hypothesis that they were hidden in an underground storage at 34 Świętojerska street.

Even if the ruins reach five storeys high, we must find the Archive!

Rachela Auerbach was one of only three people from the group of Emanuel Ringelblum’s closest associates – aside from Bluma and Hersz Wasser – who had survived the war. Still, only Hersz Wasser (who managed to jump out of a train going to Treblinka in 1943) knew where the Ringelblum Archive was exactly located. Even though finding the Ringelblum Archive became a priority issue after the war – discussed at the meeting of the Board of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland on 4 June 1945 – the operation was difficult and complex, both due to the financial cituation of the CCJP, as well as the high cost of the excavation works, which required digging through tons of rubble. Still, the effort continued. Rachela Auerbach called for beginning of the excavation works and for financial support (for example during the commemoration of the third anniversary of the Ghetto Uprising). The permission to begin excavation works was obtained in mid-August 1945, but preparations took another year. Eventually, the works began in mid-September 1946, thanks to funding from the American Jewish Labor Committee.

On 18 September 1946, in the afternoon, ten metal boxes with the first part of the Archive were unearthed. Michał Borwicz described this moment in words which are worth quoting in full:

Where was the Archive buried? Our colleague Wasser, present during the unearthing, was there, when the boxes were being hidden. But back then, you walked in differently; our directions were confused. Once the ceiling was „propped”, the digging began; we knew that the Archive we are searching for could be hidden one meter deep underground. The shovels were throwing away one decimeter of soil after another. We were stood there – the members of the Historical Commission: Wulf, Blumental, Wasser and me, we looked at each other, guessing by our looks the same thoughts: will it happen at all...? Suddenly, a shovel came across „something hard”. After a while, the first metal box emerged. In the second chamber – two other ones... the moment of discovering the underground archive was followed by deep emotion. [5]

This moment was recreated on film by Natan Gross – where the boxes were lifted by Michał Borwicz and Hersz Wasser. The recording was used in the film Mir lebngebliebene (We, the survivors, 1948).

Transcription of the documents began on 23 September, at the office of the CJHC at Sienna street, in the former Berson and Bauman hospital. The documents were in a catastrophic condition. The boxes weren’t properly welded and water leaked in. According to Michał Borwicz, Dangerous mushrooms have developed inside. Bundles of precious documents have absorbed water and swollen, so they lay close to each other, tightly adjusted to the metal walls. As a result, it may seem that the box is full of a wet, flexible mass. In order not to damage it during taking out, the metal is being torn. Now, each of these pieces of paper, of whose there are thousands, has to be carefully separated from the rest, then spread on tissue paper, which has to be regularly replaced. Thin paper – which was often used for writing preserved documents – which had been leaked on for four years breaks at a slightest shock. As the works develop, floors, tables and shelves in the large hall (turned into conservators’ workshop) are covered with growths of books, sheets, pieces wrapped in filtering tissue paper. Objects are undergoing surgeries and diets, are going through recovery period and slowly return to their original shape. Certain documents, written with „wartime ink”, were completely damaged by water. But these are only exceptions. In most cases, the writing was well preserved, both ink and pencil. The same with numerous prints, typed documents, copies. Photographs have suffered more. Moisture damaged layers of emulsion and glued together whole piles of prints. [6]

The documents were carefully described and secured. Until 25 November 1946, the work had been done by a team of ten people. As Eleonora Bergman notes, Wasser’s contribution mustn’t be ovelooked: he was marking documents with cards including informations about authors or contributors, which he only knew. Without these cards, out knowledge would be much smaller. [7]

The second part of the Ringelblum Archive was accindetally discovered during construction works at the Muranów estate, on 1 December 1950.

-----------------------

On September 12, 2019 was signed a cooperation agreement between the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute and the State Archaeological Museum in Warsaw regarding the conservation of two of the three metal boxes in the Institute’s collections, in which the first part of the Ringelblum Archive was hidden.

Footnotes:

[1] Aleksandra Bańkowska, Agnieszka Haska,...w podziemiach wymienionych domów zakopane są... Poszukiwania Archiwum Ringelbluma, Zagłada Żydów. Studia i materiały, nr 12/2006, p. 321.

[2] Ibidem.

[3] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, translated by Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

[4] Eleonora Bergman, Opublikować wszystko, do ostatniego papierka. Od odnalezienia do pełnego wydania Archiwum Ringelbluma, Midrasz. Pismo Żydowskie, styczeń/luty 2017, nr 1 (195).

[5] Michał Borwicz, Pieśń ujdzie cało… Antologia wierszy o Żydach pod okupacją niemiecką, Lublin 2012, p. 42–45.

[6] Ibidem.

[7] Eleonora Bergman, Opublikować wszystko, do ostatniego papierka. Od odnalezienia do pełnego wydania Archiwum Ringelbluma, Midrasz. Pismo Żydowskie, styczeń/luty 2017, nr 1 (195).

Bibliography:

Aleksandra Bańkowska, Agnieszka Haska,...w podziemiach wymienionych domów zakopane są... Poszukiwania Archiwum Ringelbluma, Zagłada Żydów. Studia i materiały, nr 12/2006.

Archiwum Ringelbluma. Konspiracyjne Archiwum Getta Warszawy, t. 11: Ludzie i prace „Oneg Szabat”, oprac. A. Bańkowska, T. Epsztein, Warszawa 2013.

Eleonora Bergman, Opublikować wszystko, do ostatniego papierka. Od odnalezienia do pełnego wydania Archiwum Ringelbluma, Midrasz. Pismo Żydowskie, styczeń/luty 2017, nr 1 (195).

„Pieśń ujdzie cało…”, Antologia wierszy o Żydach pod okupacją niemiecką, opracował i szkicem wstępnym poprzedził Michał M. Borwicz, 2012 Lublin, s.42–45.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, translated by Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, Wyd. ŻIH, Warszawa 2017.