- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Treblinka burning during the uprising. Photo taken by Polish railwayman Franciszek Ząbecki. Collection of the Jewish Historical Institute

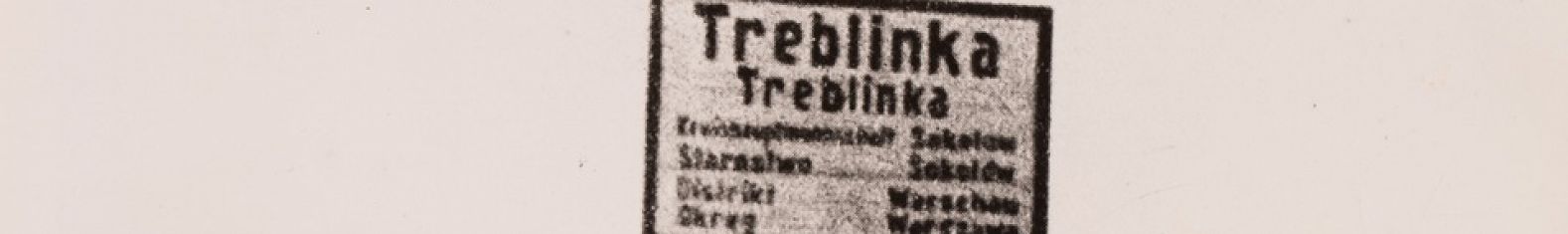

A small station called Treblinka

To the east of Warsaw, along the Bug River, there are dense pine and leafy forests. There are sad wastelands, villages are rare. Both the pedestrian and the rider avoid narrow sandy paths where the leg gets stuck, and the wheel sinks to the very axis in deep sand.

Here, by the Siedlce railway line, there is a tiny, neglected Treblinka station, located slightly more than 60 kilometers from Warsaw, near the Małkinia station, where railroads from Warsaw, Białystok, Siedlce and Łomża intersect .[1]

– this is how Vasily Grossman, a Russian writer and war correspondent, described in 1945 the place where the Treblinka extermination camp operated only a year and a half earlier – the second-largest Nazi death machine after Auschwitz.

The extermination camp, located in the middle of a forest, in a rather sparsely populated area, next to the intersection of railway lines, resembled images from Auschwitz or Dachau to a small extent. Chaos rather than the legendary German Ordnung ruled there. Most of the victims were murdered immediately after arriving with the exhaust gas from an engine removed from a Soviet tank. The crew consisted of several dozen Germans and Ukrainians from auxiliary SS formations, mostly former prisoners of war. The Germans built Treblinka in the spring of 1942 and the first transports of Jews arrived there on July 23 that year, as part of the great deportation from the Warsaw ghetto.

![treblinka_plan_ARG II 384_4.jpg [156.68 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/7/30/b9113d257c8a0374bbc8570e1c60df2f/jpg/jhi/preview/treblinka_plan_ARG%20II%20384_4.jpg)

The technique of genocide

Trains – most often made up of cattle wagons – arrived at the platform of the extermination camp which was camouflaged in such a way as to resemble an ordinary railway station. Many Jews died on the way due to lack of air. Others, transported from Germany, Austria, as well as from the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Greece, Macedonia, Bulgaria, traveled to "resettlement" by passenger trains. It was only moments before their death that they found out about their true destiny. The greatest number of Treblinka victims came from occupied Poland – apart from the ghettos from the biggest cities, Warsaw, Białystok and Radom, there were Jews from Lublin, Mazovia and Podlasie. Approximately 2,000 Roma were also murdered in the camp.

Upon arrival at the camp, the victims were forced to undress and leave all their luggage – clothes, valuables and other property were collected and sorted by the prisoners. Mountains of clothes and everyday objects, as big as houses, were dumped in the warehouses. Then the SS men drove the naked victims to the gas chambers, beating them and lashing them with whips. Women had their hair cut. A handful of people from some of the transports were selected to "work" in the prisoners' unit serving the camp – members of this unit were often murdered. After death in the gas chamber – the gassing of one group of people took about 20 minutes – the prisoners dragged the bodies of the victims outside using hooks. Under the watchful eye of the SS men, the prisoners searched for valuable objects in the body's openings, tearing out their gold teeth. The corpses were then buried in huge mass graves. [2]

After the visit of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in February 1943, the Germans began to burn the bodies of the victims. Using an excavator, they digged the bodies out of the ground and burned them on grates made of railroad rails. There was no labor camp in Treblinka II (although a labor camp for Poles, Treblinka I, operated nearby until 1944). Very few of the prisoners, those who were most persistent and whom the Germans needed most, such as Jankiel Wiernik, a carpenter from Warsaw, managed to survive for more than a few months. Each of the prisoners had to fight for survival and protect themselves from the bullets of the Germans and Ukrainians.

Chaos in the camp was an opportunity for the underground movement. Tormented prisoners, forced to serve the genocidal process every day, planned a rebellion. Obtaining weapons from a German warehouse was essential for his success. Fortunately, the Germans, not expecting any armed resistance, neglected security measures and the prisoners managed to forge the invaluable key to the arsenal.

Rebellion through the eyes of Samuel Rajzman

Samuel (Shmuel) Rajzman, translator and accountant, born in 1904 in Węgrów (town located 70 km east of Warsaw), in 1942 deported from Warsaw to Treblinka, recalled the day of the uprising in an account deposited at the Jewish Historical Institute:

Before my eyes is the vividly unforgettable day when, after long waiting, the command of our organization gave the order "To action". The mood that prevailed in the camp at that time cannot be defined in any way. The prisoners realized that the fight was hopeless for them, that no one would manage to break through the barbed wire and the thugs’ protection. Everyone realized their last day was coming, but the urge for revenge, this desire to end once and for all with this factory, which consumed some 3 million of our brothers and sisters, [3] dominated everything.

The news came to us in very scarce amounts from the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, it gave us a lot of encouragement to undertake our work. Just as the insurgents of the Warsaw ghetto undertook a hopeless fight only to retaliate, at least in a small part, for this huge harm to the martyrdom of the Jewish nation, we in Treblinka decided that Treblinka must cease to exist once and for all. (...)

![rajzman_relacja_301_7250_2.jpg [173.45 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/7/30/0441bdc91c5f3ec94049c6eccaf47966/jpg/jhi/preview/rajzman_relacja_301_7250_2.jpg)

If the insurgents of the Warsaw ghetto could count on help from outside, if they could obtain a certain number of weapons (...), we in Treblinka were left only to our own efforts. When developing an action plan, the command of the uprising was rather heading towards the complete destruction of the camp, and less consideration was given to saving a small part of the prisoners. Another argument behind this line of action was that it was much easier to obtain flammable materials such as gasoline and kerosene inside the camp than to obtain weapons.

(...)

At the forefront is our disinfector with a large spray apparatus, in which, instead of [liquid] disinfectant, 25 liters of gasoline are placed. Communication with the second camp was established through colleague Wiernik. Colleagues who are supposed to get weapons out of the arsenal are formed into a squad. The command over them is taken by Eng. Sudewicz from Częstochowa. Forged arsenal keys are prepared, carts used to carry rubble should now deliver weapons and receive additional workers, proven comrades, who are properly instructed on how to act in case one of the thugs detected a load on the cart.

Final adjustments to the team line-up, final glances towards graves, burning bodies, residential barracks and the march to work! It is strange that for the first time after a 12-month stay in Treblinka, colleagues feel not as convicts who may die at any moment, but as people who decide their own fate and walk to work, knowing that only few hours separate them from the moment of retaliation. (...) The mood in the groups is very hectic and excited, but without the slightest fear of imminent death. (...)

Due to the excited mood in the camp, our executioners apparently realized that something was not happening, and Hauptscharführer Küttner, who was most suspicious, sniffed the situation out. He would run around the camp like a mad dog to sniff out what was going on. (...) it was decided that the action, originally scheduled for 4:45 pm, must be immediate. Our liaison comes out of breath and informs us about the decision of the Command. From now on, everyone strains their ears to catch the desired signal to start the action.

From now on, the combat group is on alert, at the checkpoints, and those colleagues who have not been given weapons, with a hard hand grasp their pickaxes and crowbars as substitute weapons. Without words, as with only with expressive looks, one seems to repeat the oath to another once more. Images of miserable life in the camp run through our minds in no time, and it is clear that none of our colleagues will succumb to feat and each will carry out their task with full awareness and responsibility. Our group does not care that on all observation towers there are executioners with machine guns and that we are surrounded on all sides by ukrainians and germans. [4] Everyone's only desire is revenge, to pay for our brothers and sisters.

3:45 pm – we hear the long-desired shot at the main gate of our barracks. Strong detonations of bursting grenades follow, and in the same second, the men of my group, who were in possession of weapons, immediately take their posts. The first shot is fired from the rifle of comrade Monk from Warsaw, who aims at the ukrainian Zugwachman [watchman], putting him dead on the spot. The ukrainians were surprised by the accidents, the more so as our entire group ran yelling "hurray" at the torturers. The grenades detonated at once, and the entire area of the northern camp stood immediately in one cauldron of smoke and flames. I watched closely that fires started on all sides of the camp simultaneously and a heavy curtain of smoke covered the entire camp. It was as if providence had finally stood up for us and for the millions of innocently murdered women and children.

The life and death struggle begins.

Our liaison, comrade Anigsztejn, is the first to fall, and at the last moment, standing close to me, he calls "boys, do not lose hope, we are fulfilling a sacred duty!".

At the moment, I observe from a distance that my friends, who had been isolated from us, are starting to break through from the second camp. Several ukrainians are pursuing these colleagues. Then I give an order to shoot at the ukrainians who were chasing our colleagues.

The fight is on...

Comrades are fighting fiercely with the advantage on our side. The "heroes" in the battles with naked women and children are helpless this time and completely confused in the situation.

I am trying to connect to the southern side of the camp, where our commandant Galewski and Dr. Leichert were supposed to be, but the burning buildings of the german administration and ukrainian barracks absolutely prevent the passage of Kurt Zeidlstrasse, the only way to the south. I take advantage of the confusion of the germans, and seeing that our task has been completely accomplished, I gave the order to pave the way out of the camp. We got to the barbed wire that was cut by the group that created an escape route to the nearest forest.

With our hearts overflowing with joy, we looked at the puffs of smoke rising from the burning place where our brothers, our disgraced and tormented sisters, wives and mothers suffered, and where thousands our children were innocently martyred.

Treblinka has disappeared from the face of the earth, one place of the raging bestiality and degenerate cruelty of Hitlerism has disappeared. [5]

![treblinka pierwsza komisja_DZIH F19_1.jpg [146.68 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/7/30/3ad6461f7dc85f5286d22a5a8f3ce638/jpg/jhi/preview/treblinka%20pierwsza%20komisja_DZIH%20F19_1.jpg)

A handful of survivors

About 700 of the 840 prisoners in the camp took part in the uprising – all those who were able to stay on their feet. The insurgents managed to overwhelm or kill at least a few watchmen and set the camp buildings on fire, but the Germans soon opened fire on them and took reinforcements. The fire exchange lasted about 10 minutes, the entire uprising about 20-30 minutes. A column of smoke from the burnt buildings rose above Treblinka – unfortunately, the gas chambers were not set on fire. The Germans chased the escaping prisoners.

After they controlled the situation, the Germans sent a few more transports to Treblinka. In November, the camp ended its activities – also because Operation Reinhardt itself, the plan to murder all Polish Jews, was coming to an end. In November 1943, the Germans demolished all the buildings, plowed the area and sowed lupine. About 800-900 thousand people were murdered in Treblinka. No trace was to be left after one of the greatest crimes in history.

Nearly 100 insurgents from Treblinka survived the war. Among them was Samuel Rajzman – a Polish farmer kept him in his home until the end of the war. After 1945, Rajzman went to France, then to Canada. For the second time in his life, he started a family. He testified in the trials of Treblinka commandants. He died in 1979 in Montreal. [6]. The last participant in the rebellion, Samuel Willenberg, died in 2016.

Footnotes:

[1] Ilja Erenburg, Wasilij Grossman, Czarna księga [The Black Book], transl. Małgorzata Buchalik et al., ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, introduction by Marek Radziwon, Warsaw 2020, p. 679-680.

[2] Basic information on the functioning of the camp can be found follows the website of Treblinka Museum: https://muzeumtreblinka.eu/informacje/treblinka-ii/, access 30.07.2021.

[3] Early estimates of the number of those murdered in Treblinka, e.g. in Grossman's account, amounted to 3 million victims. It is now known that this number fluctuated around 800-900,000 murdered.

[4] Original spelling, typical for reports from death camps written after the war.

[5] Samuel Rajzman, Samuel Rajzman – relacja [Samuel Rajzman – report] (Polish language only), JHI Archive, Central Jewish Library, access 30.07.2021. The spelling has been corrected and simplified in most places.

[6] A.S., Samuel Rajzman – więzień T2, Treblinka Museum, https://muzeumtreblinka.eu/informacje/rajzman-samuel/, access 30.07.2021.