- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

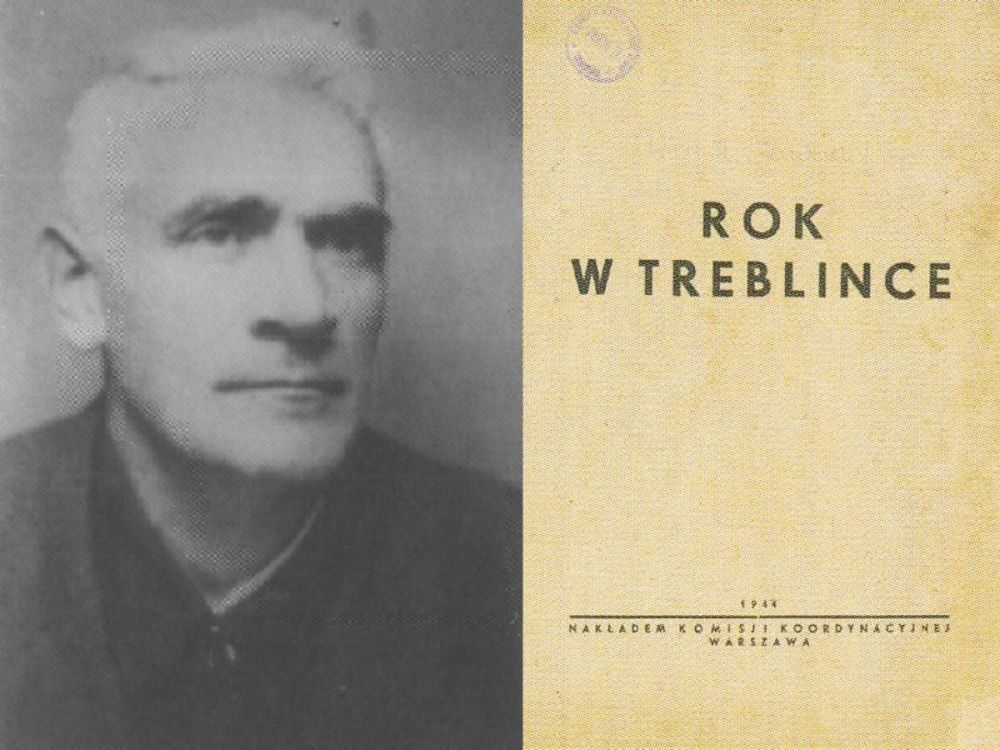

Jankiel Wiernik, ’A Year in Treblinka’ title card /

Jankiel Wiernik (also Jacob, Yankel in English sources) was born in 1889 in Biała Podlaska in eastern Poland. Before the war, he lived in Warsaw, worked as an administrator of a house belonging to the family of Stefan Krzywoszewski, who was a playwright and former director of municipal theaters in Poland’s capital. At the beginning of August 1943, Wiernik reached Krzywoszewski’s apartment at Smolna 25 street. He had a terrifying account of almost a year spent in the German Nazi extermination camp in Treblinka, where he was transported on August 23, 1942. [1]

After coming to Treblinka

‘DEAR READER!

For your sake alone I continue to hang on to my miserable life, though it has lost all attraction for me. How can I breathe freely and enjoy all that which nature has created?’ [2] – Wiernik wrote in the first words of his account. Captured by the Germans during the great deportation from the Warsaw ghetto, he went to Treblinka – like all Polish Jews sent there – in an overcrowded cattle car. Even so, some people who sent to death did not fully realize where the train was going.

‘At 4 p.m. the train got under way again and, within a few minutes, we came into the Treblinka Camp. Only on arriving there did the horrible truth dawn on us. The ukrainians[3] were standing on the roofs above the barracks with rifles and machine guns.The camp yard was littered with corpses, some still in their clothes and some naked. Their faces distorted with fright and awe’.

In the first days after his arrival, Wiernik was forced to segregate looted property and bury the murdered victims in mass graves. When the overseers found out that he was an experienced carpenter, they sent him to construction works in the camp. During these works, Wiernik watched the operation of the death machine.

Men ‘had to undress in the yard, make a neat bundle of their clothing, carry the bundle to a designated spot and deposit it on the pile. They then had to go into the barrack where the women had undressed, and carry the latter’s clothes out and arrange them properly. Afterwards, they were lined up and the healthiest, strongest and best-built among them were beaten until their blood flowed freely. Next, all the men, and women, old people and children had to fall into line and proceed from Camp No. 1 to the gas chambers in Camp No. 2. Along the path leading to the chambers there stood a shack in which some official sat and ordered the people to turn in all their valuables. The unfortunate victims, in the delusion that they would remain alive, tried to hide whatever they could. But the German fiends managed to find everything, if not on the living, then later on the dead. Everyone approaching the shack had to lift his arms high and so the entire macabre procession passed in silence, with arms raised high, into the gas chambers. A Jew had been selected by the Germans to function as a supposed „bath attendant.” He stood at the entrance of the building housing the chambers and urged everyone to hurry inside before the water got cold. What irony! Amidst shouts and blows, the people were chased into the chambers. As I have already indicated, there was not much space in the gas chambers. People were smothered simply by overcrowding. The motor which generated the gas in the new chambers was defective, and so the helpless victims had to suffer for hours on end before they died. Satan himself could not have devised a more fiendish torture. When the chambers were opened again, many of the victims were only half dead and had to be finished off with rifle butts, bullets or powerful kicks. Often people were kept in the gas chambers overnight with the motor not turned on at all. Overcrowding and lack of air killed many of them in a very painful way.’

Wiernik witnessed hundreds of thousands of people being led to their deaths. He saw the opening of new gas chambers, unsuccessful attempts to burn the corpses, and above all, the unimaginable chaos of mass murder, carried out with sadism, amidst shots, screams and torture. Several times it happened that a Jew, a Jewess or the entire transport resisted the Germans or tried to escape – the guards then killed them with particular cruelty. The same fate awaited the prisoners who tried to escape and were captured.

Apart from the German crew, most of the guards were Ukrainians. ‘They were recruited mainly from among Soviet prisoners of war and underwent ideological training in the camp in Trawniki near Lublin,’ writes historian Edward Kopówka, director of the Treblinka Museum. – ‘They were officially referred to as Trawnikimänner, and the local population called them wachmen or the blacks (due to the color of their uniforms). Mostly, they were young people aged 19–30, armed with rifles and bayonets.’ [4] ‘The Ukrainians were constantly drunk,’ writes Wiernik, ‘and sold whatever they managed to steal in the camps in order to get more money for vodka. The Germans watched them and frequently took the loot away from them. When they had eaten and drunk their fill, the Ukrainians looked around for other amusements. They frequently selected the best looking Jewish girls from the transports of nude women passing their quarters, dragged them into their barracks, raped them and then delivered them to the gas chambers.’

Not only cattle cars with Jews from Warsaw, Białystok and other ghettos from Masovia and Podlasie regions of Poland came to Treblinka, but also passenger carriages with Jews from Germany and Austria, the conquered countries of Western Europe and the Balkans. These people did not expect death at all, they came with large supplies of food and valuable items. The Germans lied to the Jews from outside Poland until the end that Treblinka was only a stage in the journey to the East.[5]

‘The German fiends were particularly pleased when transports of victims from foreign countries arrived. Such deportations probably caused great indignation abroad. Lest suspicion arise about what was in store for the deportees, these victims from abroad were transported in passenger trains and permitted to take along whatever they needed. These people were well dressed and brought considerable amounts of food and wearing apparel with them. During the journey they had service and even a dining car in the trains. But on their arrival in Treblinka they were faced with stark reality. (…) The next day they had vanished from the scene’. Almost only Jews were murdered in Treblinka – a few transports with Poles and Gypsies also came to the camp.

The fate of prisoners

Contrary to the Bełżec camp, where almost all the Jews who were brought in were immediately murdered in the gas chambers, and the members of the Sonderkommando burying the bodies lived very briefly, in Treblinka a certain number of prisoners were forced to do construction work, sort looted property, clean gas chambers, collect wood for the camp. There was also an orchestra of 10 musicians. The deputy commandant, Kurt Franz, invented the camp anthem which the prisoners had to sing every day. Franz also organized cabarets, football matches, and even Jewish weddings and funerals. His ruthlessly pitted the prisoners with his dog, a giant St. Bernard named Barry, shouting ‘Mensch, faß den Hund!’ (‘Man, get the dog’).

![jankiel_wiernik_main_1_fb.jpg [342.68 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/2/5/772bff8d36d37c1e2fc207c67f1db84e/jpg/jhi/preview/Kurt_Franz_Treblinka_wiki.jpg)

‘The number of transports grew daily, and there were periods when as many as 20,000 people were gassed in one day, with all 13 gas chambers in operation. All we heard was shouts, cries and moans. Those who were left alive to do the work around the camps could neither eat nor control their tears on days when these transports arrived. The less resistant among us, especially those belonging to intelligentsia, suffered nervous breakdowns and hanged themselves when they returned to the barracks at night after having handled the corpses all day, their ears still ringing with the cries and moans of the victims. Such suicides occurred at the rate of 15 to 20 a day. These people were unable to endure the abuse and tortures inflicted upon them by the overseers and the Germans.’

Members of the camp commandos were beaten every day. Wiernik managed to avoid being murdered when the officer who had tormented him was transferred. Later, Wiernik participated in the construction of new gas chambers and watchtowers. The ‘rotation’ of prisoners was high – they were often murdered after the completion of the work.[6] Preparations for the rebellion began only when the Nazis began killing members of the camp commandos less frequently.

According to Wiernik, in 1943, after the Germans discovered the mass graves of Polish officers in Katyn and suffered defeats at the Eastern Front, the SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered the burning of the bodies of the murdered in order to better cover up the traces of the crime. Previously, the corpses were simply thrown into huge mass graves dug by an excavator. Cremation specialist Herbert Floss, brought to Treblinka from Bełżec, ordered not only the bodies of the victims of the latest transports to be burned, but also to dig of decaying bodies from the ground:

‘A fire grate made of railroad tracks was placed on concrete foundations 100 to 150 meters in length. The workers piled the corpses on the grate and set them on fire. I am no longer a young man and have seen a great deal in my lifetime, but not even Lucifer could possibly have created a hell worse than this. Can you picture a grate of this length piled high with 3,000 corpses of people who had been alive only a short time before? As you look at their faces it seems as if at any moment these bodies might awaken from their deep sleep. (…) If you stood close enough, you could well imagine hearing moans from the lips of the sleeping bodies, children sitting up and crying for their mothers. (…) The gangsters are standing near the ashes, shaking with satanic laughter. Their faces radiate a truly satanic satisfaction. They toasted the scene with vodka and with the choicest liqueurs, ate, caroused and had a great time warming themselves by the fire.’

‘In one instance, when a batch of corpses was placed on the fire grate, an uplifted arm stuck out. Four fingers were clenched into a tight fist, except for the index finger, which had stiffened and pointed rigidly skyward as if calling God’s judgment down upon the hangmen. It was only coincidence, but it was enough to unnerve all those who saw it. Even our tormentors paled and could not turn their eyes from that ghastly sight. It was as if some higher power had been at work. That arm remained pointed upward for a long, long time. Long after part of the pyre had turned to ashes, the uplifted arm was still there, calling to the heavens above for retributive justice. This small incident, seemingly meaningless, spoiled the high good humor of the hangmen, at least for a while.’

‘Whenever I started on a new job, I knew that my life would be spared for a few weeks longer because as long as they needed me, they would not kill me. (…) The guard at the camp was increased and it became impossible to get from camp 1 to camp 2. Seven men joined in a plot to dig a tunnel through which to escape. Four of them were caught and were tortured for an entire day, which in itself was worse than death. In the evening, when all hands had returned from work, all the inmates were ordered to assemble and witness the hanging of the four men. One of them, Mechel, a Jew from Warsaw, shouted before the noose was tightened around his neck: „Down with Hitler! Long live the Jews!”

The uprising

‘We decided that by spring we would either make a try for freedom or perish.’ Wiernik turned out to be so necessary for the Germans that they did not kill him even when he fell ill with pneumonia. They ordered him to build more guardhouses and buildings in the camp. As one of the few prisoners, Wiernik was able to move relatively freely within the limits of the sub-camps, and even between them. He was in camp 2, where about 300 prisoners burned the bodies of gassed victims. He used the work on the construction of the camp gate to communicate with the conspirators from camp 1, where there were about 700 prisoners – in this part of the camp, Jews left the trains and gave their property.

‘In Camp No. 2 we began to organize into groups of five, each group being assigned a specific task such as wiping out the German and Ukrainian garrison, setting the buildings on fire, covering the escape of the inmates, etc. All the necessary paraphernalia was being prepared: blunt tools to kill our keepers, lumber for the construction of bridges, gasoline for setting fires, etc. The date for starting the revolt was set for June 15, but the zero hour was postponed several times and new dates were set, because the time was not yet ripe.

‘For quite some time I had been working in Camp No. 1, returning every evening to Camp No. 2. This gave me a chance to make contact with the insurgents in Camp No. 1. I was watched less than the others and also treated better.

The Jewish commander of camp 1, Galewski, told Wiernik to calm down young Jews from camp 2, who were most eager to fight, and wait for the final signal. ‘I had the feeling that zero hour was approaching and that the end was really in sight. On my return home from work that evening, I called a meeting to check the state of our preparedness. Everybody was excited and we did not sleep at all that night, seeing ourselves already outside the gates of the inferno.’

On August 2, Kurt Franz was with a group of watchmen on the Bug, probably taking a bath in the river. This meant that on the day of the uprising the camp staff was weakened, but one of the cruelest executioners could not get into the hands of the insurgents.

‘Suddenly we heard the signal – a shot fired into the air.

‘We leaped to our feet. Everyone fell to his prearranged task and performed it with meticulous care. Among the most difficult tasks was to lure the Ukrainians from the watchtowers. Once they began shooting at us from above, we would have no chance of escaping alive. We knew that gold held an immense attraction for them, and they had been doing business with the Jews all the time. So, when the shot rang out, one of the Jews sneaked up to the tower and showed the Ukrainian guard a gold coin. The Ukrainian completely forgot that he was on guard duty. He dropped his machine gun and hastily clambered down to pry the piece of gold from the Jew. They grabbed him, finished him off and took his revolver. The guards in the other towers were also dispatched quickly. (…) Within a matter of minutes, fires were raging all around. We had done our duty well.’

‘From a distance of several kilometers one could see a column of black smoke above the camp,’ writes Edward Kopówka. – ‘From the commandant’s office, Stangl [Franz Stangl, the camp commander] managed to establish contact with the units stationed nearby. Units from Małkinia, Sokołów Podlaski, Kosów Lacki and Ostrów Mazowiecka rushed to help.’ [7] Over 700 of the 840 prisoners in the camp took part in the uprising — the rest were too exhausted to fight. About 200 people managed to escape outside the camp and escape the manhunt, and about 100 people lived to see the end of the war. Among them was Jankiel Wiernik, saved thanks to the jamming of the revolver of the Ukrainian who was shooting at him. He arrived in Warsaw exhausted, ‘still carrying a bloodied ax, with which he killed a guard during his escape.’[8]

First, the Krzywoszewskis took care of the Wiernik, then their neighbor, Mrs. Bukowska. He received false documents under the name of Kowalczyk. In the winter of 1944, he wrote down his memoirs from Treblinka, which were printed on the initiative of the Council to Aid Jews, the Jewish National Committee and the Bund. The brochure was distributed by the resistance movement in occupied Poland. It was also microfilmed and delivered to London.

In August 1944, Jankiel Wiernik took part in the Warsaw Uprising. After the war, he emigrated to Sweden, and then to Israel. He testified in the trials of Ludwig Fischer, the governor of the Warsaw district of the General Government from 1939 to 1945, and Adolf Eichmann, one of the main organizers of the extermination of Jews – both criminals were executed. During Eichmann’s trial, he made a model of the Treblinka camp. He died in the Ghetto Heroes Kibbutz in Israel in 1972, at the age of 83.[9]

Footnotes:

[1] Władysław Bartoszewski, Historia Jankiela Wiernika, in: Jankiel Wiernik, Rok w Treblince [A Year in Treblinka], Warsaw 2003, p. 5.

[2] Original 1944 translation of Wiernik’s text was used. See Jankiel Wiernik, op. cit., p. 43–87. Typesetting errors were corrected and some sentences and words omitted from the original or mistranslated were added or corrected.

[3] In his account, Wiernik usually writes the names of Germans and Ukrainians in lowercase. This has been preserved in this article.

[4] Edward Kopówka, Treblinka. Nigdy więcej, Muzeum Walki i Męczeństwa w Treblince, Siedlce 2002, p. 20.

[5] Ibid., p. 31.

[6] Basic information about the camp: ibid., p. 20–25.

[7] Ibid., p. 42.

[8] W. Bartoszewski, op. cit., p. 5.

[9] Ibid., p. 6–9.