- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Szyja (Jehoszua, Szaja) Rabinowicz was born in 1888 in a renowned Hassidic family. He was the son of a rabbi from Biała and a descendant of Jakow Icchak Rabinowicz from Przysucha, known as The Holy Jew. His wife was a great-granddaughter of Menachem Mendel, a famous rabbi from Kock. Rabinowicz refused to become a Hassidic rabbi, causing outrage in his family. He joined Bund and participated in the 1905 revolution. He was arrested and freed after Hassidim from Biała bribed the Russian police. [1]

Before the war, he was an owner and manager of a roof tile factory. He donated a significant part of his income to the cause of supporting Jewish culture, such as the YIVO Institute, where he probably met Emanuel Ringelblum, founder of the Archive.

In the Warsaw Ghetto, Rabinowicz dedicated himself to social and cultural activities. He was a member of the Inter-district Commission of Home Committees and the Kuchen Labour Rationalization Committee, he also joined the Ikor organization. According to Abraham Lewin’s diary, he lived most likely at 3 Dzika street. [2]

He was one of the founders and a board member of Oneg Shabbat, as well as an informal connection between the group and Bund. Aside from Landau and Winter, he was one of the financial supporterts of the group. He participated in the „Two and a half years of war” project, but it appears that he didn’t gather the evidence. When after the war Hersz Wasser, Oneg Shabbat’s secretary, was identifying documents from the Archive, he assigned only one of them to Rabinowicz. It was dedicated to the branch in which he was working in – production of roof cover material (Production of roofing felt. The significance of Jews in production of roofing felt before the war and the shift during occupation).

In his political orientation this man, a wealthy salesman from an orthodox family, was a loyal Bund member. Honesty, moral clarity and dedication to social work were his distinct qualities which earned him respect and esteem among anyone who remained in contact with him. [3]

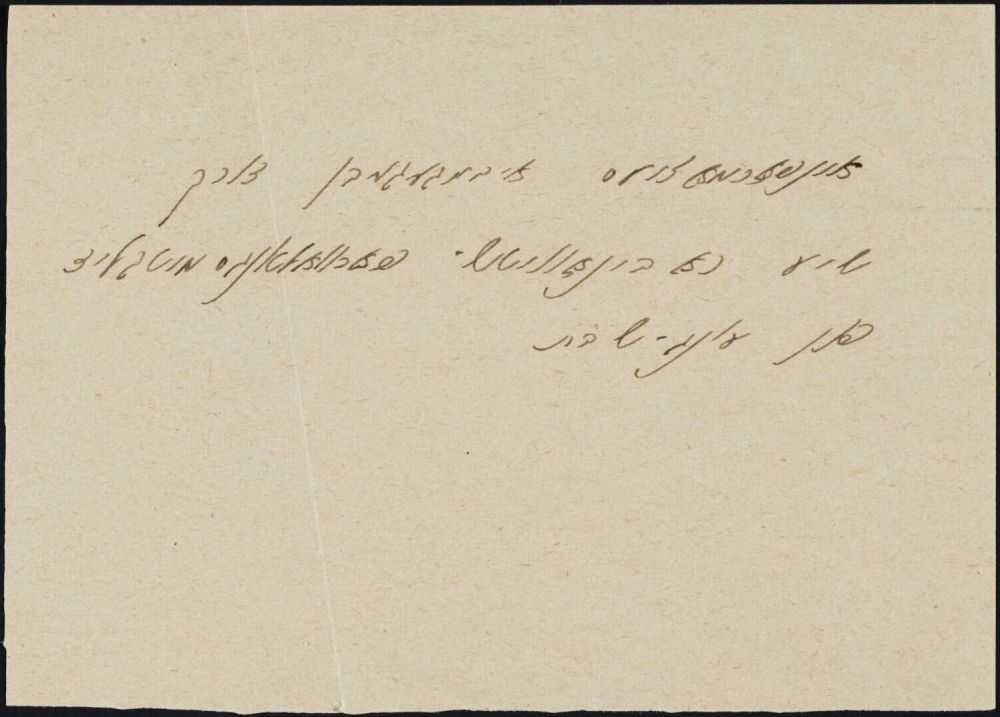

![rabinowicz_2.jpg [262.04 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/49ee079b5b1e6de6e8e67cfc52fc6302/jpg/jhi/preview/rabinowicz_2.jpg)

Szyja Rabinowicz, Production of roofing felt / The Ringelblum Archive

A post-war obituary written by Bund called Rabinowicz „the tzaddik of the Warsaw Ghetto”. According to the same source, he was „leading the archive committee” at the clandestine Bund. In January 1943, Rabinowicz and his family tried to hide on the „aryan side”. Soon, a tragedy happened – his wife and younger daughter were shot by Gestapo. Rabinowicz returned to the ghetto and tried to save himself by buying a false passport to one of the South American countries. Together with about 2,500 othe Jews, he was waiting for his departure at an internment camp in the Polski Hotel. In 1943, he was transferred from there to the Bergen Belsen transitional camp in Germany. Survivors recalled Rabinowicz giving lectures about the Yiddish-language culture and Jewish history in the camp. [4]

On 11 October 1943, the Germans deported him to Auschwitz-Birkenau – in the same transport as Jewish writer Szyja Perle and Natan Buchsbaum, leader of Poale-Zion Left. He was murdered immediately upon arrival, along with all the prisoners from the same transport.

The report Production of roofing felt. The significance of Jews in production of roofing felt before the war and the shift during occupation can be found in the 34th volume of the Ringelblum Archive.

Written by: Anna Majchrowska

Translated by: Olga Drenda

Footnotes:

[1] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017, sp 287-288.

[2] Ciężko żyć, nie ma żywności, nie ma gdzie spać. Nocuję: na Dzikiej 3 (a), u Rabinowicza na podłodze, z Recymerem [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, vol. 23, ed. Katarzyna Person, Zofia Trębacz, Michał Trębacz, University of Warsaw, Warsaw 2015, p. 136.

[3] Michał Mazor, The Vanished City [in:] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, op. cit., p. 287-288.

[4] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, op. cit., p. 287-288.

Bibliography:

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie, part II, vol. 34, ed. Tadeusz Epsztein, WUW, Warsaw 2016.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Jechiel Jeszaja Trunk, Pojln: obrazy i wspomnienia z Łodzi (Jechiel Jeszaje Trunk, Pojln, vol. 1–7, New York 1953, vol. 7, p. 201–217.