- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Władysław Szlengel /

Władysław Szlengel was born in Warsaw in 1912 or 1914. [1] The Szlengel family were living in Warsaw, in a tenement house at 14 Waliców street. The father, Maurycy Szlengel, was a painter and set designer (he died in 1934), and mother, Mala nee Wermus, died in 1936. We don’t have extensive information about the poet’s immediate family – we know that he had a brother (or brothers) and a wife, whose name we don’t know.

Szlengel graduated from the School of Trade ran by the Warsaw Merchant Society. During the interwar period, he was publishing in magazines such as ’Nasz Przegląd’ (where he debuted on 31 August 1930 with a poem Potassium cyanide), ’Chochoł’, ’Szpilki’, ’Robotnik’, ’Sygnały’. His works were concerned with themes such as Jewish identity, Polish-Jewish relations and current international events. His songs were recorded before the World War II at Syrena-Electro and Odeon, performed by such popular artists of the 1930s as Adam Aston, Mieczysław Fogg and Wiera Gran. He was also writing Polish versions of international hits and movie theme songs. His songs written in andrus (streetwise, urban style) style mirrored the folklore of Warsaw, popularized characters from the lower classes, the street and the world of crime (Panna Andzia ma wychodne, Jadziem, panie Zielonka, Dziewczyna z Podwala). He was writing lyrics for cabarets, such as Cyrulik Warszawski, Ali Baba and revues — Wielka Rewia, Małe Qui Pro Quo, Tip-Top.

When the World War II began, he fought in defence of Warsaw. After the September campaign, he managed to escape with his wife to Białystok, where he worked as an event host and literature director at the Polish Miniature Theatre. Later, he moved t Lviv, where he worked at the Lviv Miniature Theatre. When the Soviet-German war broke out, he returned to Warsaw, and together with his wife, he moved in again to the house at Waliców street, which was a part of the ghetto.

In the Warsaw Ghetto, he continued his work as a poet and an artist. In the Sztuka cafe at Leszno street, he organized a literature theatre, where the most popular song was Jej pierwszy bal (Her first ball), performed by Wiera Gran, with words by Władysław Szlengel, and music by Władysław Szpilman (based on the To dawny mój znajomy waltz from Ludomir Różycki’s opera Casanova). A special attraction, established in March 1942, was Żywy Dziennik (Live News), short poems, trifles, puns, parodies – an ironic chronicle of the ghetto. Szlengel was one of the founders of this regular show, which resembled a daily newspaper in its form and contents. He was writing lyrics, hosting the event, but also performing on stage as an actor.

According to Ringelblum, Szlengel’s songs and poems enjoyed popularity and moved listeners to tears, because they were up to date, they dealt with themes which were a part of the ghetto’s daily life. [2] They were recited at literary meetings, distributed in typescripts or on hectograph copies. Halina Birenbaum, a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto, recalled that Szlengel’s poems were read out loud in the evenings at home, in the factories, at workplaces, copies circulated about in written copies and in spoken word. Written in the ghetto, directly, in the hellish burning trance of these days – they were a living image of our emotions, thoughts, pain and merciless struggle for every moment of our lives. [3]

Szlengel himself wrote: My poems (…) were written in the pauses of horrible events whose echoes reached you as well, my friends. Like smiles calming down a dyring person between one strike of pain and another – these sad rhymes and rhythms were appearing” [4]. In his poems, he also documented the Holocaust of the Jews. After the Great Deportation, Szlengel’s poems became a chronicle of current moods, hopes and fears of people in the Ghetto. [5] The most famous poes include: A window to the other side, An account with God, Two deaths, Counter-attack, Passports, Things, A small station called Treblinka.

In his last poems, written between January and April 1943, Szlengel links the themes of Jewish and Polish resistance. Ruth Shenfeld points out that in Five minutes to midnight, Szlengel paraphrases Ordon’s redoubt by Adam Mickiewicz, an anthem to the November insurgents who fought to the end. [6]

Five minutes to midnight!!!

We weren’t told to go down

Under the attic, like cats,

We jumped up the ladder steps

Sweating with fear.

We wait for the night, from six in the morning,

we – those who consume the despair of the hour,

curled in our prisons, laid flat on the roof.

On the roof, with a dead and pale face,

a brother is hiding – one trembling Jew,

who wants to disappear in the chimney’s shadow... (...)

(translated by Olga Drenda)

He published his poems in underground poetry booklets distributed in typewritten copies: Calling in the night, A poetic denunciation, Zahlen bitte, Poems from the last days. With his future reader in mind, in January 1943 he published a volume of poems written in the ghetto – What I was reading to the dead. He added an introduction, To the Polish reader, in which he expressed hope that the book will become publicly available and maybe these pages will be read by a Polish Democrat, not oblivious to the martyrdom of a nation with whom he shared manye years, those bad and those good ones. [7]

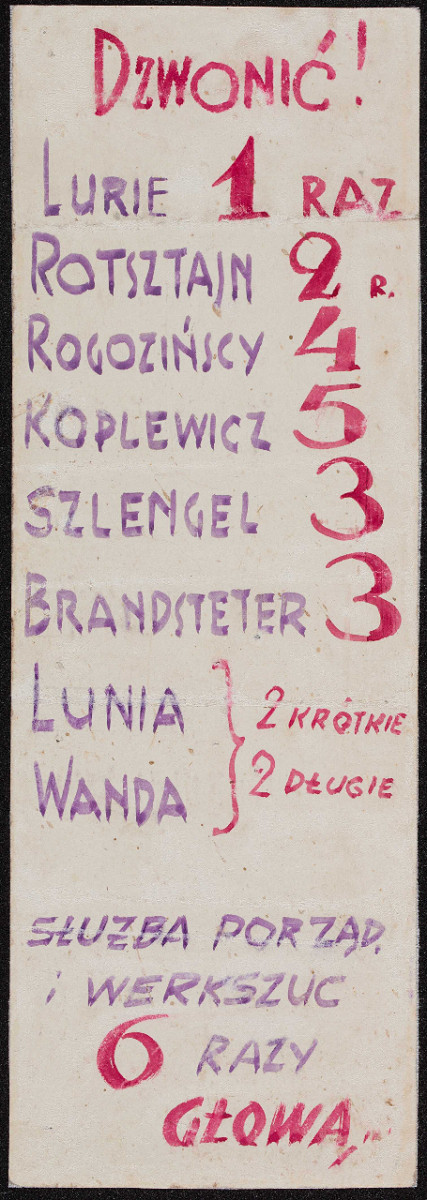

The first part of the Ringelblum Archive includes several satirical poems written by Szlengel before the Great Deportation. The second part of the Archive contains more poems, such as A small station called Treblinka, Passport, Five minutes to midnight, Telephone and Things, a poem written by Szlengel for a contest announced by the „Kultura Jutra” magazine. Kassow claims that it was unlikely that Szlengel would cooperate with Oneg Shabbat, primarily because he belonged to the Jewish police. [8] Some of Szlengel’s manuscripts were hidden in a double table top and found by accident in the 1960s. [9]

Szlengel managed to avoid deportation because he was employed at a brush factory. He lived with his wife at 34 Swiętojerska street; among his neighbours, there was Marek Edelman. He continued writing his Live News and kept announcing new episodes at literary meetings. He planned to write a novel about Polish theatre, worked on a drama A monument to Judas and on an Encyclopedia of the Warsaw Ghetto. None of these works survived.

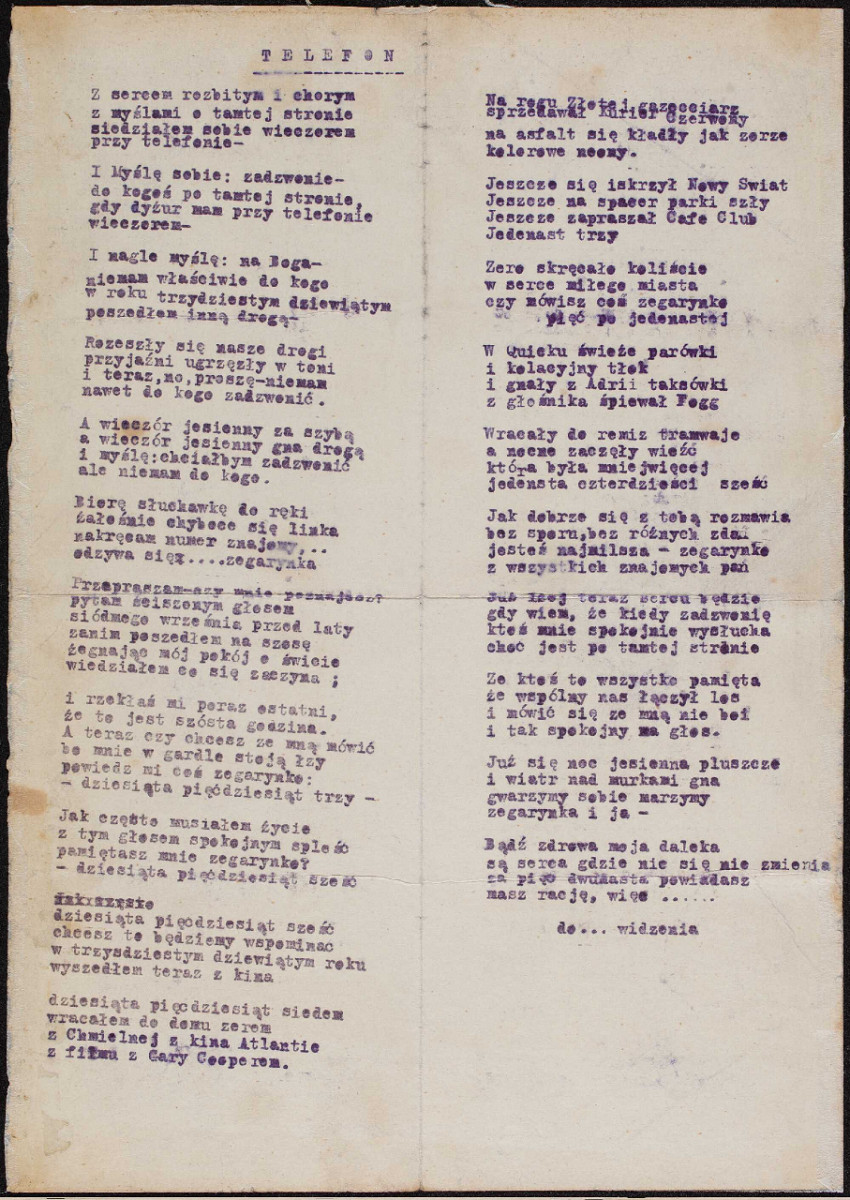

In his harrowing What I was reading to the dead, he described a selection at the brush factory, which began on 18 January 1943. After the deportations, he managed to escape the ghetto several times, posing as a factory courier. He was looking for help and support from his friends on the „aryan side”, but with no results. These experiences were mirrored painfully in his poem Telephone:

Telephone

With my broken and sick heart,

with thoughts on the other side,

I sat in the evening

By my telephone.

I thought: I will call

someone on the other side,

when there comes my turn

to sit by the telephone.

And soon I realize —

God, there’s nobody to call,

I went another way

In 1939.

Our ways have parted,

Friendships became stuck,

and suddenly, here I am,

without anybody to call. (...)

(translated by Olga Drenda)

During the Ghetto Uprising, he was hiding in Szymon Kac’s bunker at 36 Świętojerska street. When the Germans discovered the location, he was shot together with his wife on 8 May 1943.

I was supposed to read these poems to people who believed in survival, I was supposed to read this book as a memoir of a luckily survived horrible period, a diary from the bottom of hell – my companions are now gone, and within one hour, my poems became poems I was reading to the dead. [10]

----------------------------------

Szlengel’s works were published in: Archiwum Ringelbluma. Konspiracyjne Archiwum Getta Warszawy, t. 26: Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, oprac. Agnieszka Żółkiewska, Marek Tuszewicki, Warszawa 2017.

Read also: Władysław Szlengel’s unknown photograph from 1938

Sources:

https://www.jhi.pl/psj/Szlengel_Wladyslaw

http://www.jhi.pl/blog/2015–09–08-wiemy-wiecej-o-szlenglu

http://www.jhi.pl/blog/2017–05–08-wladyslaw-szlengel-zapomniana-gwiazda-warszawy

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, trans. Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Emanuel Ringelblum, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, full edition of the Ringelblum Archive, Vol. 29a, ed. Eleonora Bergman, Tadeusz Epsztein, Magdalena Siek, JHI, Warsaw 2018.

Magdalena Stańczuk, Władysław Szlengel: poeta nieznany: wybór tekstów, Bellona, Warsaw 2013.

Władysław Szlengel, Co czytałem umarłym, Text based on: Władysław Szlengel, Co czytałem umarłym, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Warsaw 1979, Published by: Fundacja Nowoczesna Polska, https://wolnelektury.pl/katalog/lektura/szlengel-co-czytalem-umarlym-tom/

Footnotes:

[1] Documents confirming his birthdate weren’t found. Most biographical notes mention 1914, but in the documents from the Propaganda and Agitation Department of the Białystok Communist Party Regional Committee (Bolsheviks) dated 1940 and including an index of writers, painters, artists and actors in the Białystok region, Władysław Mojsejewicz Szlengel is described as born in 1912 in Warsaw. The information was probably provided by the writer himself.

[2] Emanuel Ringelblum, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, full edition of the Ringelblum Archive, Vol. 29a, ed. Eleonora Bergman, Tadeusz Epsztein, Magdalena Siek, JHI, Warsaw 2018, p.208.

[3] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, op.cit., p. 520, Słowo, które nie ginie nigdy, „Nowiny Kurier”, 21 October 1983.

[4] Władysław, Szlengel, Do polskiego czytelnika [in:] Władysław Szlengel, Co czytałem umarłym, op. cit., p.10.

[5] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, op. cit., p. 526.

[6] Ibidem, p.535.

[7] Władysław, Szlengel, Do polskiego czytelnika, op. cit., p.9.

[8] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, op. cit., p. 320.

[9] Ibidem, p. 528.

[10] Władysław, Szlengel, Co czytałem umarłym, op. cit., p. 1.

The project is generously supported by the Taube Philantropies.