- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

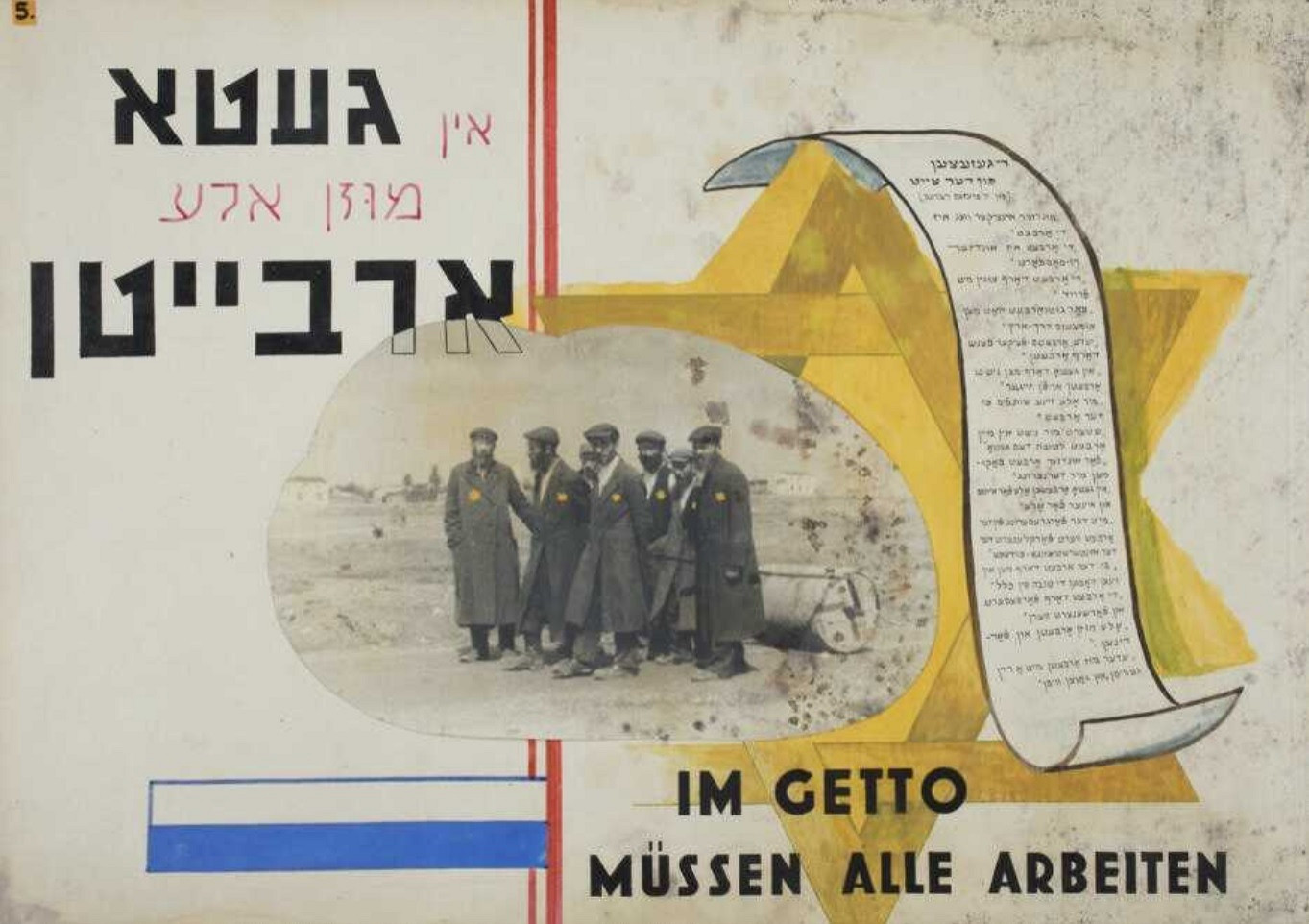

Łódź ghetto, German propaganda photo, 1941 /

Mass resettlements took place during a particularly cold winter. Initially, they were conducted according to the plan, but eventually the process turned into a chaotic escape. The Germans were organizing brutal round-ups which increased the rush among resettled people, who tried to save their belongings.

‘Chaos spread among those already living in the ghetto as well as on the streets which were not “cleansed of Jews” yet. Everyone rushed towards the ghetto in panic. This way, [Germans] achieved their goal, removing all the Jews from the streets’[1], recalled a participant of these events in an account found in the Ringelblum Archive.

Initially, Jews could still move around the city fairly at ease. Some people used this opportunity to pick up their belongings left in the abandoned flats. Soon afterwards, the ghetto area was surrounded with a wooded fence and barbed wire. The boards on the ghetto borders informed that trespassing is forbidden; the guards recruited from the German police formations and Jewish Order Service (Jewish police) were enforcing this law.

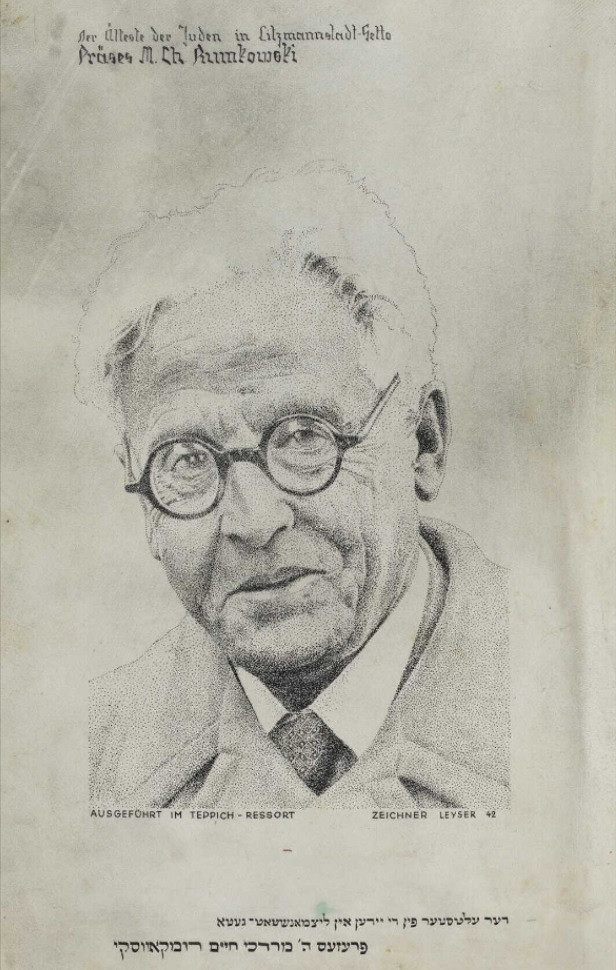

The Łódź (Litzmannstadt) Ghetto was closed on 30 April 1940. From that moment on, nobody was allowed to leave the area without a special permission. On that day, mayor Franz Schiffer sent a letter to the Head of the Jewish Council, Chaim Mordechaj Rumkowski, in which he made him responsible for enforcing the prohibition of leaving the Jewish quarter. A few days later, on 10 May 1940, Johannes Schäfer ordered to shoot the Jews who would try to leave the ghetto. Also those who would try to get into the city illegally could have been shot. Almost one year later, on 11 April 1941, the order to use guns was extended onto anyone, also non-Jewish, who would try to trespass the ghetto border.

‘On 1 May 1940, two years ago, more than 160 thousand living, breathing people were surrounded with wooden planks and barbed wire and cut off from the world’[2], wrote Józef Zelkowicz on 1 May 1942. It was true: that many people were locked on an area only slightly larger than 4 square kilometres.

Rumkowski had a large margin of freedom in organizing the ghetto’s inner life. He established an administration apparatus fairly quickly – particular departments were responsible for various areas of life in the ghetto: food, accommodation, education, healthcare and others. The Jewish administration was obliged to provide rooms for people resettled to the ghetto. Rumkowski was the only person allowed to contact the German authorities, on the basis of a permission issued by the mayor of Litzmannstadt.

On 30 April 1940, on the day of closing of the ghetto, the Head of the Jewish Council organized a meeting of his closest associates and presented a plan of organizing the ghetto:

‘From tomorrow, the ghetto will be closed. We will be locked here, without income, and without an ability to earn money. When one of the members of the authorities asked me how I imagine providing basic existence for thousands of people in the ghetto, I replied: “Our work is our currency”. We have to put [our] work skills to use in order to secure existence for as many people as we can. We should not delude ourselves or count on a quick end of this war, quite the contrary – we should do what we can to provide labor to as many Jews as possible. In order to make this plan work, we have to introduce, even in a miniature form, a number of new offices and governing bodies, like in every normal state. Don’t laugh at this name – we will begin with ministries, dealing with the most important issues: labor, health, food provision, finance and economy. As for further ones, life will show soon what sort of offices will be necessary. We have our own police, administration and postal administration, we will also have our own currency’[3].

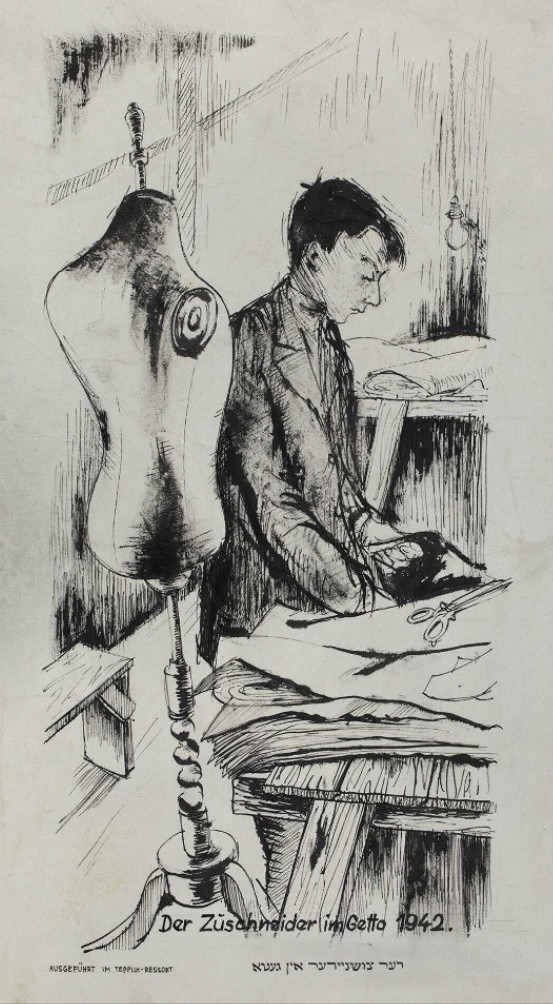

It was true that aside from the extensive administration apparatus, Rumkowski created a production machine. The Łódź Ghetto included many resorts – factories and workshops, hospitals, a post office; from a certain point, there was also a local currency, Markquittungen called ‘chaimki’ or ‘rumki’ by people. They had no value outside the ghetto. The formidable administration system was ran by the Head of the Jewish Council. Everything was organized according to his main principle – providing work for the German occupant, which was supposed to secure the existence of the ghetto.

‘Work is our only way’, Rumkowski would often repeat, believing that the Jews’ contribution to the German war effort increases their chances of survival. When the German authorities decided to deport part of the ghetto’s occupants, they chose the unemployed, the sick, children, the elderly, as well as ‘the antisocial element’ – the criminals. This way, after the most tragic deportations from autumn 1942, when over 15,000 children and elderly people were sent to the Kulmhof am Nehr (Chełmno nad Nerem) extermination camp, the ghetto was in fact turned into a labor camp. By the end of 1943, 117 factories and workshops there employed almost 74,000 people – more than 85% of the general population. The majority of production from the resorts was delivered to the Germans. More than 70% was commissioned by the state authorities, the army, the police and paramilitary formations. Private companies were commissioning goods to a smaller extent.

The Łódź Ghetto existed from 8 February 1940 to 29 August 1944. During that time, about 45,000 people died due to famine and disease. The vast majority of the inmates were murdered in Kulmhof am Nehr and Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camps. It is estimated that only between 5,000 to 7,000 people survived until the end of the war.

See the whole Album of the Carpet Factory from the Łódź Ghetto in the Central Judaic Library

![logos_TaubePhilanthropies.png [7.41 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2020/12/11/f10aa2f8473e22e198a5258cd5f57e7d/png/jhi/preview/logos_TaubePhilanthropies.png)

The project is generously supported by the Taube Philanthropies.

Sources:

Archiwum Ringelbluma. Konspiracyjne Archiwum Getta Warszawy. Losy Żydów łódzkich (1939–1942), vol. 10, edited by Monika Polit, Warsaw 2013.

Encyklopedia getta. Niedokończony projekt archiwistów z getta łódzkiego, publ. by Monika Polit, Krystyna Radziszewska, Adam Sitarek, Jacek Walicki, Ewa Wiatr, Łódź 2014.

Józef Zelkowicz. Notatki z getta łódzkiego 1941–1944, ed. M. Trębacz and others, Łódź 2016.

Andrea Löw, Getto łódzkie/Litzmannstadt Getto. Warunki życia i sposoby przetrwania, Łódź 2012.

Adam Sitarek, Otoczone drutem państwo, Łódź 2015.

Dorota Siepracka, Stosunki polsko-żydowskie w Łodzi podczas okupacji niemieckiej [in:] Polacy i Żydzi pod okupacją niemiecką 1939–1945. Studia i materiały, ed. Andrzej Żbikowski, Warsaw 2006, p. 691–762.

Przypisy:

[1] Archiwum Ringelbluma. Konspiracyjne Archiwum Getta Warszawy. Losy Żydów łódzkich (1939–1942), vol. 10, ed. Monika Polit, Warsaw 2013, p. 118.

[2] Józef Zelkowicz. Notatki z getta łódzkiego 1941–1944, ed. Michał Trębacz and others, Łódź 2016, p. 69.

[3] See: Adam Sitarek, Otoczone drutem państwo, Łódź 2015, p. 93–94. See also: Andrea Löw, Getto łódzkie/Litzmannstadt Getto. Warunki życia i sposoby przetrwania, Łódź 2012, p. 81.