- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Relocation of the Jews to the ghetto / February — April 1940 /

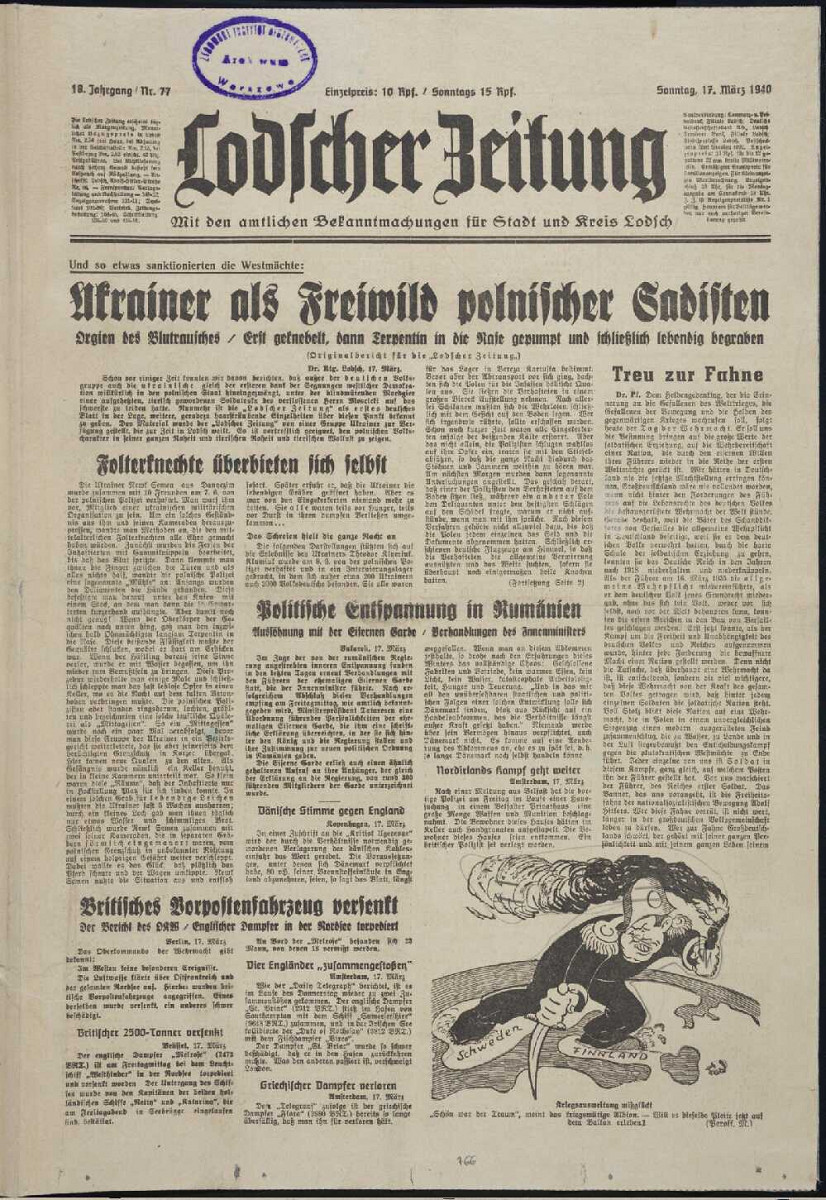

On 8 February 1940, chief of the police, SS-Brigadeführer Johannes Schäfer issued a regulation regarding the rights of stay and residency for the Jews (in German: „Polizeiverordnung über die Wohn — und Aufenthaltsrechte der Juden”). One day later, the order was published in „Lodscher Zeitung”. The German authorities announced that, according to the regulation, a „Jewish district” was established in the city. The important fact is that the word „ghetto” wasn’t mentioned in the document. The district was established in the Northern part of the city, in the Old Town and Bałuty district, a poor and densely populated area with a large Jewish community. Over 160,000 people were soon relocated to an area as small as 4,13 square kilometre, and after a small modification, the ghetto area reached further east, to the Jewish cemetery.

In the designated area, there were 2332 houses, with 28,400 rooms altogether. The majority of these buildings were old and poor, often made of wood. The density of the population was immense. In 1942, 42,587 people were living on one square kilometre, with 6–7 people per one room [1].

The information that the ghetto is being established had terrified the Jewish community; gossip about relocation to a „closed district” had already been circulating since January.

The way from the city to the ghetto is short in a geographical sense, hardly noticeable. But the way we had to go through in a mental, physical, moral sense, was very long, hard and marked with blood [2].

A few days later, on 12 February, mass resettlements of Jews began, while Poles and Germans (49,000 people) were relocated elsewhere from the assigned ghetto area.

They were moving in freezing cold, with a handful of belongings packed in a rush. Whoever could, organized a sled or a carriage. People who used to be well off, who contributed to the city’s economy, were now walking down the street pulling miserable trolleys. Some bedding and underwear, a couple of domestic goods was everything they were left with. The streets northwards were full of people. Some „aryan” passers-by were insulting the Jews and laughing at crowds on the streets [3].

The resettlement of Jews to the ghetto was taking a long time. Originally, it was organized according to a weekly schedule. The relocation was controlled by German police, who appeared in apartments and ordered immediate leave. In late February, the schedules were abandoned due to their low efficiency. It caused a further extension of the relocation time, especially that this decision led to hopes of further postponement of relocating to the ghetto. Soon, they turned out to be an illusion – the Germans organized brutal round-ups in the city center.

The police were storming into apartments in which the Jews were living, ordering them to leave and go onto the street within five minutes. In one of the houses, all men wre killed, elsewhere, they were murdering entire families. Sometimes, they would abuse the Jews, forcing them to „exercise”, later shooting them or rushing them to the ghetto [4].

An especially tragic round-up began on the evening of 6 March 1940, the day remembered later as „bloody Thursday”:

There are no words to describe the cruelty, barbarism and brutality of the Nazi beasts, who were killing innocent people with calm and proficiency of executioners. Those who remained alive were robbed from all their goods, including 10 marks – an amount which was accepted before during requisitions and evacuations. That night, several children were killed, as well. The bodies of shot people were lying in puddles of blood in rooms and courtyards [5].

The result of these dramatic events turned out to be as the German authorities planned – the Jews began to relocate to the ghetto en masse. The rush led to increasing housing problems – finding an accommodation became even more difficult than before. All the places were overpopulated; the Jews had to stay former schools or prayer houses turned into shared lodgings, where they were waiting for their assigned rooms. The round-ups had worsened the situation – in the first few days afterwards, sometimes over a dozen people would have to share one room.

Soon afterwards, between March and April 1940, the ghetto area was surrounded with a wooden fence and barbed wire. On the borders, plaques were informing that crossing was forbidden. The area was guarded by German police formations and Jewish Order Service (Jewish police). On 30 April 1940, the Łódź Ghetto, separated from the other areas of the city, was closed. From that moment on, „the Jewish tragedy, in the most precise sense of the word, began”. [6]

---

The Łódź Ghetto existed from 8 February 1940 until 29 August 1944. In that time, about 45,000 people had died due to famine and epidemics. Most prisoners were murdered in the death camps in Chełmno nad Nerem (Kulmhof am Nehr) and Auschwitz-Birkenau. It is estimated that only 5–7,000 people had survived until the end of the war.

Footnotes:

[1] J. Baranowski, Getto Litzmannstadt [in:] Żydzi berlińscy w Litzmannstadt Getto 1941–1944. Księga pamięci, oprac. I. Loose, Łódź 2009, s. 35.

[2] Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute Archive, 302/11–13, Pamiętnik Leona Hurwicza.

[3] A. Löw, Getto łódzkie/Litzmannstadt Getto. Warunki życia i sposoby przetrwania, Łódź 2012, s. 73.

[4] Ibidem, s. 74.

[5] Archiwum Ringelbluma. Konspiracyjne Archiwum Getta Warszawy. Losy Żydów łódzkich (1939–1942), t. 10, red. M. Polit, Warszawa 2013, s. 117.

[6] J. Poznański, Dziennik z łódzkiego getta, Warszawa 2002, s. 25.

Bibliography:

Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute Archive.

Archiwum Ringelbluma. Konspiracyjne Archiwum Getta Warszawy. Losy Żydów łódzkich (1939–1942), t. 10, red. Polit M., Warszawa 2013.

Löw A., Getto łódzkie/Litzmannstadt Getto. Warunki życia i sposoby przetrwania, Łódź 2012.

Poznański J., Dziennik z łódzkiego getta, Warszawa 2002.

Sitarek A., Otoczone drutem państwo, Łódź 2015.

Żydzi berlińscy w Litzmannstadt Getto 1941–1944. Księga pamięci, oprac. Loose I., Łódź 2009.