- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

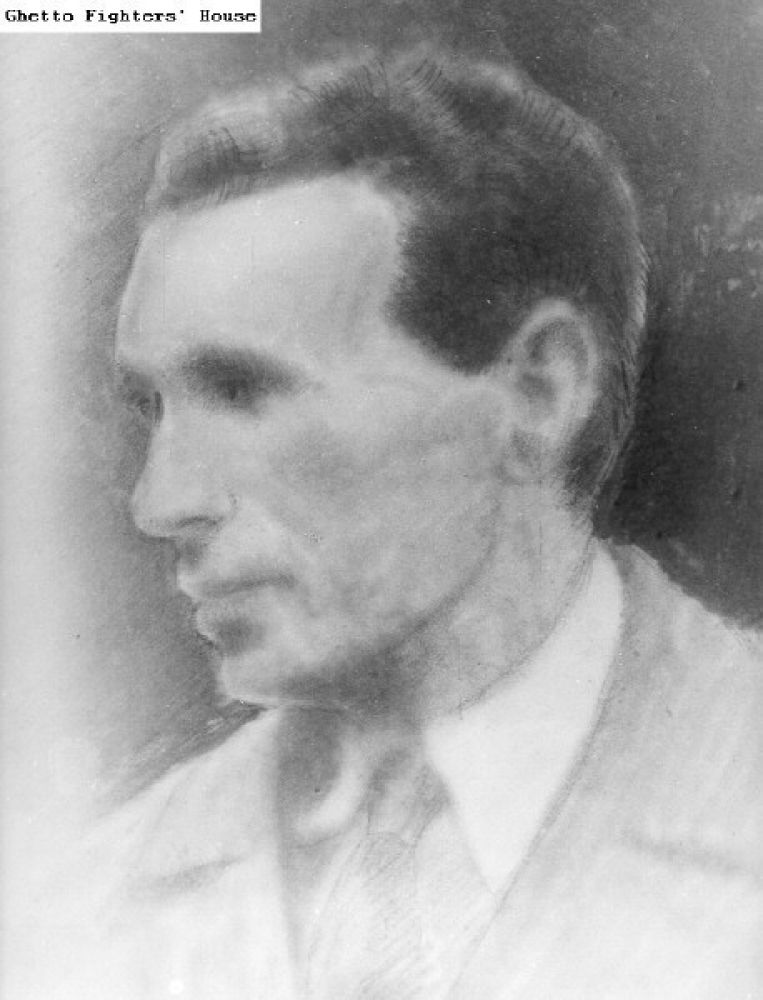

Perec Opoczyński / Ghetto Fighters House Archive

Perec Opoczyński was born on 15 October 1892 in Lutomiersk near Łódź, in a poor, religious family. Perec’s father, Simcha Eliezer, linked Hassidic piety with interest in secular literature and culture. [1] Because his mother’s wish was for him to become a rabbi, after his father’s death he enrolled in a yeshiva in Łask, and later in a progressive Talmudic school in Kossovo in Lithuania, where he learned Polish and Russian. Because of this, he became seen as an apostate in Lutomiersk. He gave up education and found a job as a shoe upper makes and shop assistant in a shop with cotton. Still, he intended to continue to learn. He moved to Frankfurt am Main, but due to lack of money, he had to return to Poland and take up a job in a textile factory in Kalisz.

At that time, he lived in a commune of Jewish youth from religious families, who decided to follow secular education and culture – not only Jewish. He got to know young Jewish writers, such as Herszele Danielewicz and Oszer Szwarcman, who inspired him to write in Yiddish (his earlier literary attempts, which he began at the age of 12, were written in Hebrew. His sister, Rina Opoczyński (Opper-Opoczyński), moved to the United States in the 1920s.

As a citizen of the Kingdom of Russia, he was drafted into the Tsarist army when World War I broke out. With an injured hand, he found himself in a POW camp in Hungary, where he spent the next four years. Together with his relative Awrom Opoczyński, he was editing and publishing the „Jidyszer Krigsgefangener” („Jewish Prisoner of War”) magazine.

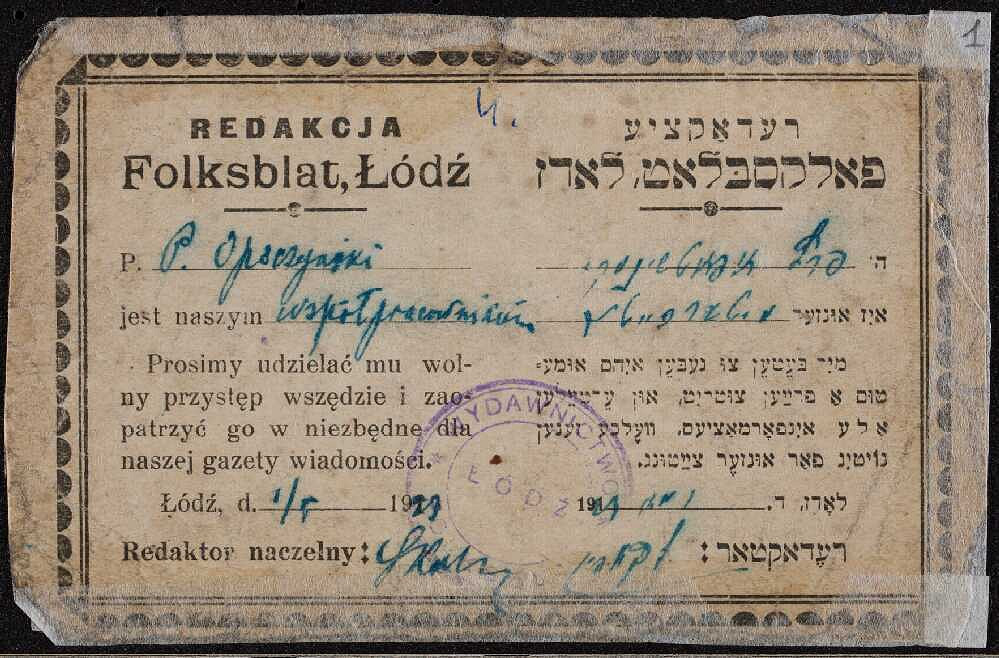

In the interwar period, he worked as a Hebrew teacher in Kłodawa, where he also met his future wife Mindla Rzeszewska. When they got married, they moved to Łódź, where Opoczyński opened a small shoemaker’s workshop. He didn’t give up his literary ambitions. In 1921, he began to contribute to the „Folksblat” Łódź daily, andfour years later, to „Lodzer Tageblat”. He also worked as an editor of the popular weekly „Ilustrirte Lodzer Wochnblat. Wochencajtung far Gezelszaftleche, Politisze un Kulturele Inionim” („Illustrated Łódź Weekly. Social, Political and Cultural Weekly”) and wrote for the „Ilustrirter Pojliszer Menczester” monthly. At that time, renowned Jewish artists were often visiting the Opoczyńskis’ apartment. In 1933, Perec’s only book was published – a volume of Hassidic-themed poetic prose, Nawenad. Despite trying, he never joined the art and literature elite.

Melech Rawicz recalled Opoczyński: He was strange. Silent (…) One time, he would look at you with great respect, while another time, with a hint of disdain. (…) Always immersed in his secrets and painful experiences (…) He entered the world of literature, attracted like a moth to light. [2] Unfortunately, the Opoczyński family was affected by a tragedy at that time. Two of their children, Biniumen and Miriaml, developed polio and died. The writer experienced a mental breakdown. In 1935, he moved to Warsaw together with his wife, and accepted an offer to work in „Dos Naje Wort”, periodical of the Poalej Syjon-Lewica organization, whose Opoczyński was a dedicated member of since 1927. In the same year, Perec and Mindla’s third son, Danczik (Daniel) was born. They were living in very miserable conditions at 21 Wołyńska street, where the poorest Jews lived.

Cooperation with Oneg Shabbat

Emanuel Ringelblum didn’t invite journalists to cooperate with him out of concern that they won’t be able to keep the work confidential and won’t live up to the standards of scientific objectivism. He wrote: We deliberately didn’t invite professional journalists, because we didn’t want our work to become schematic. We wanted the description of events in any small town, of the experiences of every Jew – and every Jewish person during that war was a separate, individual world – to be conveyed in as simple and as true way as possible. Any gratuitous word, any literary coloring of facts, any embellishment would stand out and cause disgust. The Jewish life during this war is so full of tragedies that it doesn’t need any extra words. Another issue was the question of keeping a secret, and it is commonly known that one of the journalists’ main disadvantages is that they cannot keep things confidential. [3]

Still, he made an exception for Opoczyński. According to Monika Polit, it may have been caused by the fact that Opoczyński was „a common man” and only thanks to his own effort and strength of will, he became one of the self-taught Jewish intelligentsia members, people who turned with heartfelt concern towards the world which they came from, and who Ringelblum respected so much. [4] He was also an active party member in Łódź and Warsaw.

After some time, perhaps thanks to Oneg Shabbat’s support, he found a job as a postman in the ghetto. He was responsible for the poorest streets and the refugee centres, where it wasn’t easy to find the right recipient, or – once they were found – they didn’t have money to pay for the delivery. In such situations, Opoczyński had to ask neighbours to cover the payment for the letter.

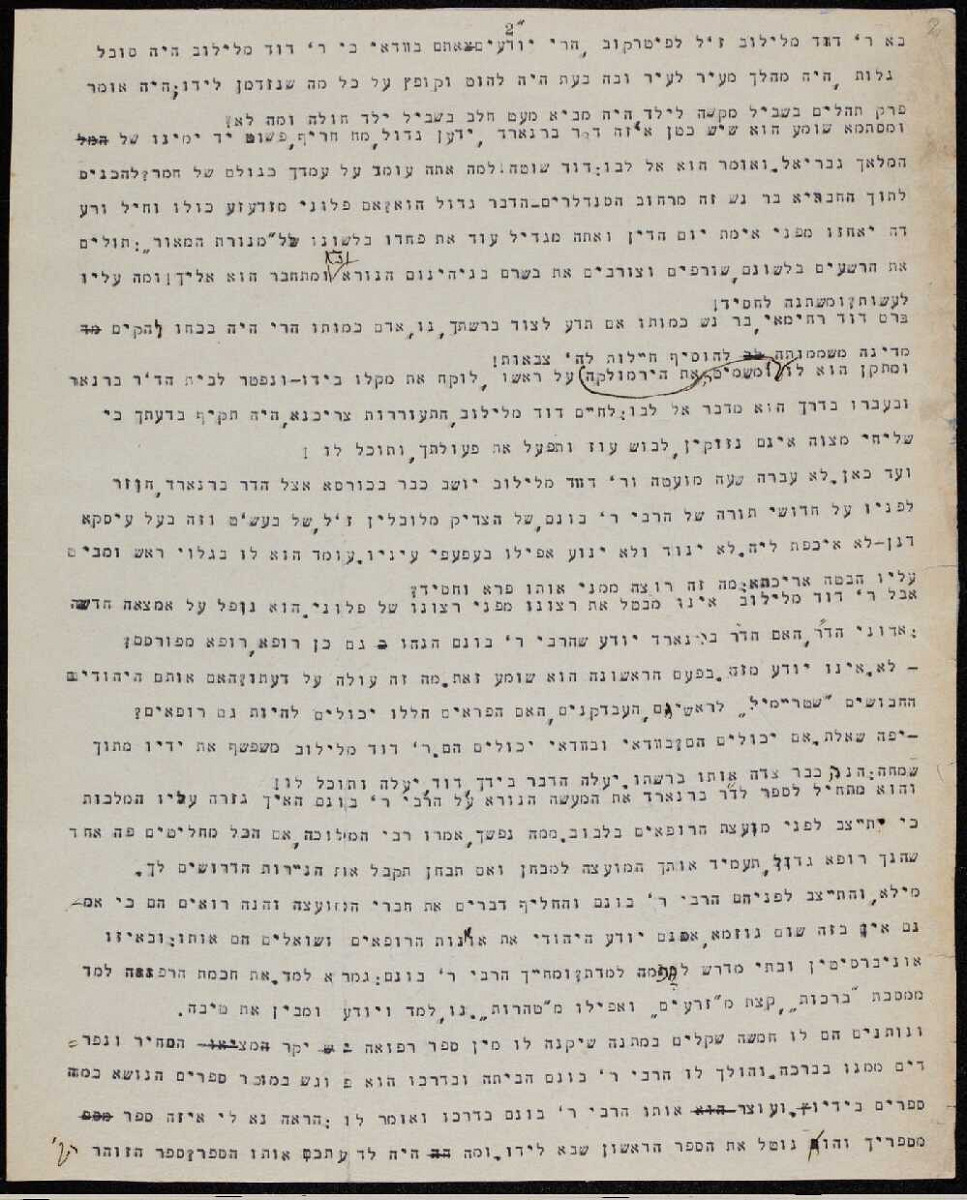

His daily wanderings through the walled district and observing the nightmare of daily existence there inspired a series of detailed reportages, for which he received a small payment. He was describing streets, yards (micro-shtetls), where the only signs of life were crying, sobbing and lament [5], the life of people from particular tenement houses, the activity of house committees, disinfection actions, so-called „steam baths” organized at the order of the German authorities in order to persecute the Jewish people, the activity of smugglers. He was covering the conditions of working in the ghetto workshops and factories, the fate of children suffering from famine, whose stories – after he lost his own children – he was especially sensitive to. His story Children on the street, written in an accusatory tone, blames the Jewish community for remaining oblivious to the horror suffered by the youngest ones.

His stories were fictionalised reportages, inspired by the style of Sholem Aleichem and I.L. Perec. Opoczyński had a great sense of observation and linguistic skill. He could remember and note down the conversations between Jewish mothers and their childrem, the slang of Jewish smugglers, the calls from young beggars on the streets, quarrels between housewives and others. [6] His stories remain a priceless linguistic source – Opoczyński used dialect, idiomatic Yiddish, smugglers’ jargon, the slang of the criminal milieu [7], thanks to which he managed to convey the behaviours and attitudes among the Jewish community.

His work as a postman gave him income, but proved to be a great challenge for someone strained by hunger and illness. He wrote about himself in a story „The Jewish postman”, for which he received an award in the Oneg Shabbat literary contest at the end of 1941. He wrote: The postman is tired. (…) The postman lives in dire poverty. He gets up on five in the morning and works until nine or ten at night. He doesn’t receive his weekly salary, but is paid per item. (…) The working conditions are so unbearable that they damage his health. But the worst things were constant resentment – because he knocks on the door too loud, because the letter was delivered too late, because the contents of the parcel were stolen, and, the most important factor, because of the fee for delivery – all of this had poisoned the postman’s life, exhausting him physically and mentally. Yet it was still nothing in comparison to the horrible images of abandonment and poverty, which the postman had to watch on his route down the valley of despair at Krochmalna, Ostrowska, Smocza, Niska. [8]

The ghetto postman’s salary didn’t allow him to support his family. His feet were swollen from hunger. Still, he manages to find resources to remain active in the party, in his house committee at 21 Wołyńska street, and to write for Oneg Shabbat. [9] Rachela Auerbach remembered him after the war as the most diligent of all.

When he caught typhus, Menachem Kon managed to find expensive medication for him and to organize extra food rations. Perec thanked him, dedicating his short story The rabbinical court to Kon.

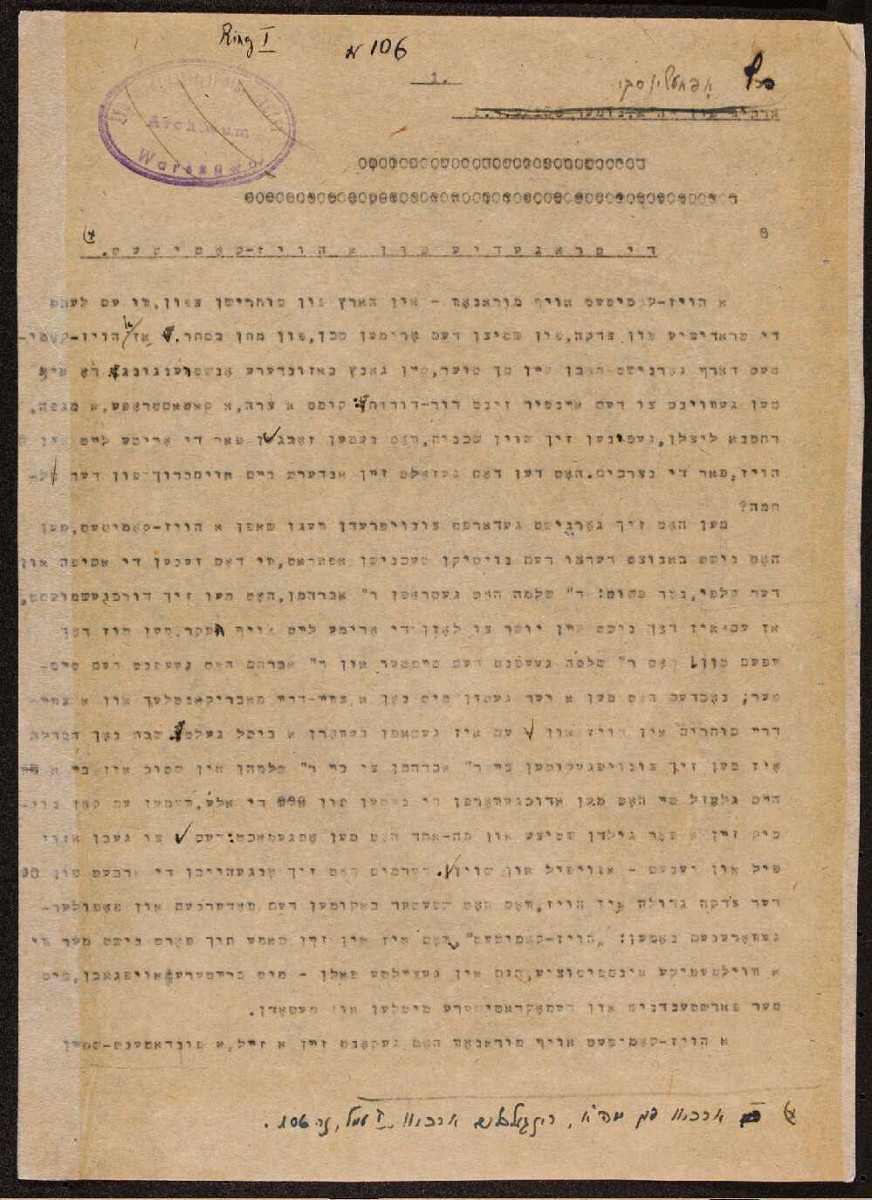

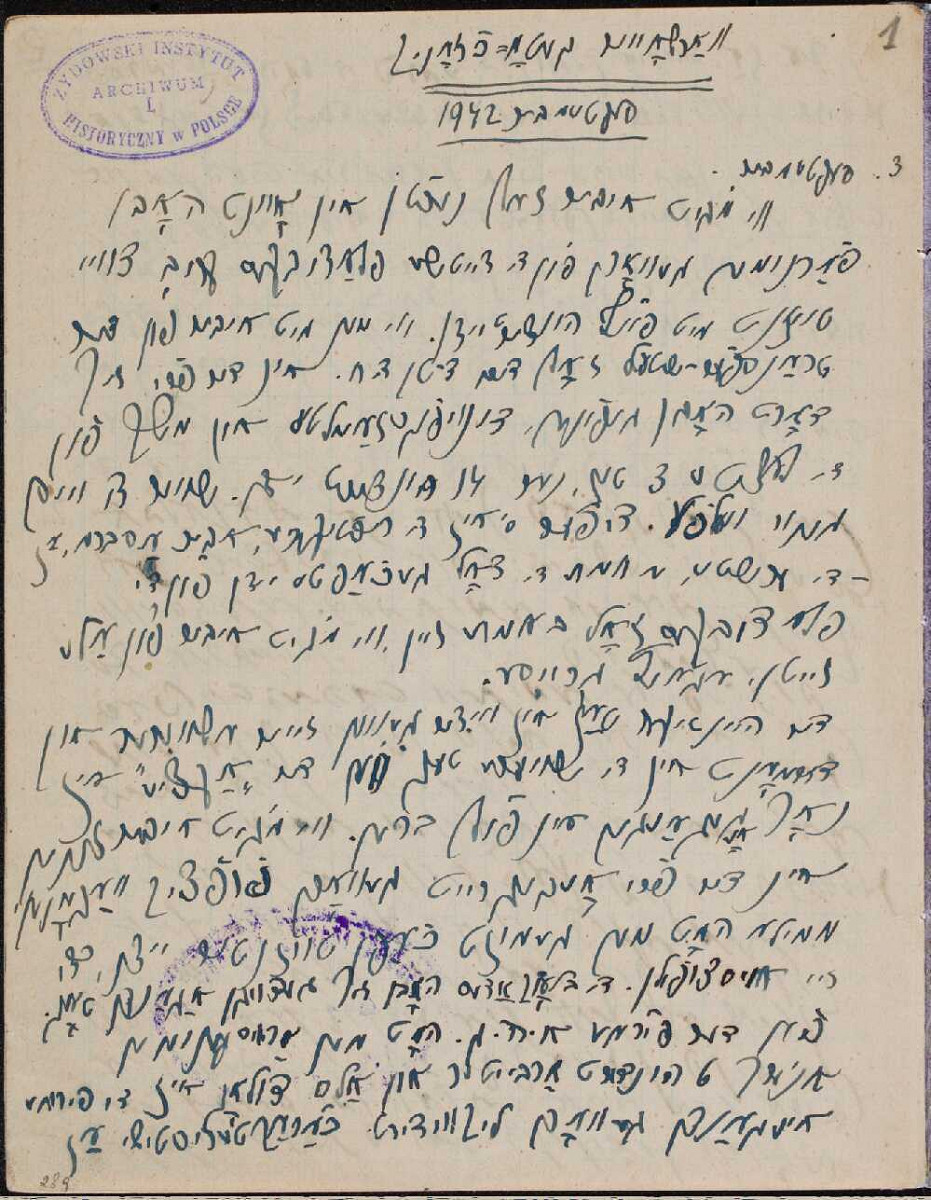

To the Archive, he contributed his short stories written before the war (based on his experiences in the POW camp in Hungary), and Hassidic stories, which Opoczyński considered to be his most important achievement (in mid-1920s, he had 270 of them ready). They are a priceless source of knowledge for a researcher of Jewish folk culture. The Archive contains also fragments of his Ghetto Chronicle (notes from may and June 1942 and September 1942-January 1943).

Opoczyński’s difficult financial condition never allowed him to fully dedicate himself to writing. I have always felt this need, but never had material possibilities to devote myself to it, he told Zalmen Rejzen. [10] Today, we know that his wartime works, which convey the cruel daily reality of the Warsaw Ghetto, became probably his most important task – in the literary and in the social sense.

Thanks to employement in the OBW workshop, he survived the Great Deportation in 1942. His last diary entry was dated 5 January 1943. He was probably killed in a manhunt in January 1943. The fate of his wife and son remain unknown.

translated by Olga Drenda

Footnotes:

[1] Monika Polit, Introduction to The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Pereca Opoczyńskiego, vol. 31, ed. Monika Polit, Wyd. ŻIH, Warsaw 2017.

[2] Ibidem, p. XX.

[3] The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, vol. 29, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, Wyd. ŻIH, Warsaw 2018, p. 500.

[4] Monika Polit, Introduction to The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Pereca Opoczyńskiego, op. cit., p. XXV.

[5] The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Pereca Opoczyńskiego, vol. 31, op. cit., p. 447.

[6] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, translated by Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, Wyd. ŻIH, Warsaw 2017, p. 330.

[7] Monika Polit, Introduction to The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Pereca Opoczyńskiego, op. cit., p. XXXIII.

[8] The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Pereca Opoczyńskiego, op. cit., p. 426.

[9] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, op. cit., p. 326.

[10] Monika Polit, Introduction to The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Pereca Opoczyńskiego, op. cit., p. XXIV.

Bibliography:

The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Pereca Opoczyńskiego, vol. 31, ed. Monika Polit, Wyd. ŻIH, Warsaw 2017.

The Ringelblum Archive, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z getta, vol. 29, ed. Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, Wyd. ŻIH, Warsaw 2018.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, translated by Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, Wyd. ŻIH, Warsaw 2017.