- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Occupational history of the Warsaw Philharmonics found their reflection in the Warsaw Ghetto. The fates of the members of the orchestra, musicians of Jewish descent and a vast number of music lovers and Philharmonics’ fans remaining within the closed ghetto walls — it is also one of the most dramatic episodes of its history. It ought to be mentioned that in interwar Warsaw, the Jews (one third of its inhabitants) constituted a loyal clientele of the Philharmonics, what is mentioned, inter alia, by Jerzy Waldorff, who writes that during the crisis of the 1930s „we considered the room of the Philharmonics to be decently filled when one quarter of the seats were taken, half of them by faithful-to-music Jews.”

Every day, the ghetto got denser and denser as a result of its borders being narrowed and at the same time of bringing into it more people from other Polish cities, and also Jews, often Christians, from some other European countries, for example Germany, Holland, Austria and Czech-Slovakia. At the turn of 1941 and 1942, around half a million people were living in the ghetto in unimaginable conditions (350 thousand Jews were living in Warsaw when the war broke out).

Even though the people confined in the ghetto had to fight to meet the basic needs, also cultural life existed there, including musical one. It may seem strange that in an unbelievable whirl of poverty, organized forms of musical activity were formed. There were many reasons behind it. There were a lot of musicians in the ghetto, former members of orchestras: the Warsaw Opera, Operetta and above all, former members of the orchestra of the Warsaw Philharmonics, not even mentioning a vast number of popular music artists (inter alia, Artur Gold, Zygmunt Białostocki, Szymon Kataszek – all of them perished). There were also many conductors, (opera) singers, dancers, choreographers, organizers of musical life, inter alia, Henryk Markiewicz (died 1942) an impresario, former director of concerts of the Warsaw Music School, also associated with the activity of the Philharmonics, musicologists, musical writers, critics.

These people, brutally shaken out of previous life, had to face poverty and hunger. They were less resourceful and more lost than for example merchants, craftsmen, doctors, who could more easily find employment and resources. Not being able to adapt to new conditions, they made desperate attempts to earn a living working in their field by forming, as their fellow artists on the „Aryan side”, street and yard groups. They played ambitious pieces, what was mentioned by one of the ghetto inhabitants, Jan Mawult. „Singing and music everywhere, on the streets, causing traffic, in the yards, in the squares. Once again, a range of singers, magnificent opera aries and songs, wonderful voices that once reverberated in concert halls and opera buildings, Verid, Puccini, Meyerbeer, Moniuszko, Niewiadomski and — oh Jewish insolence! — Schumann, Schubert and Wagner. And Polish and Jewish songs, folk songs tugging everywhere at everyone’s heartstrings in the same way...”.

Finally, more resourceful musicians, supported by the Head of the Community, Adam Czerniaków, and his wife dr Felicja Czerniaków, and Central Commission for Entertainments operating in the ghetto, decided to found the Jewish Symphonic Orchestra (ŻOS). It also had a moral aspect: it kept appearances of „normality”, met the spiritual needs of a vast number of music lovers, gave musicians a chance not only to get minimal resources, but also to remain in good musical condition. Many historians believe that the cultural activity was one of the forms of civil resistance, an activity in the teeth of the extermination actions of the occupier. It is, however, worth mentioning that from mid 1942 the people in ghettos had no idea of the planned extermination in the death camps (apparently they were being transferred to „work camps”) and they still had faith in the intervention of the allies and quick ending of the war.

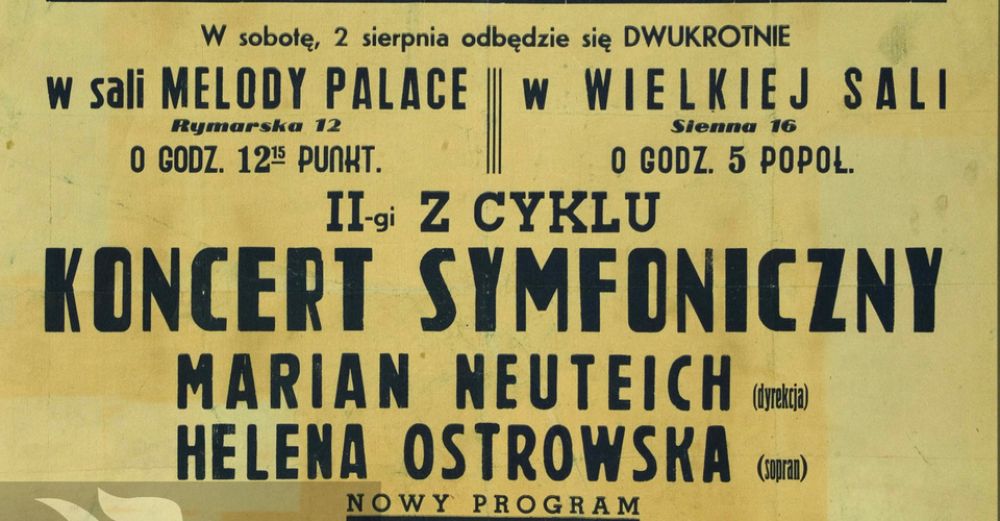

The leaders of the Jewish Symphonic Orchestra were musicians of the Warsaw Philharmonics. They included: cellists Józef Bakman and Izydor Lewak, who had been connected with the Philarmonics since the beginning, namely since 1901; violists Wacław Baruch, Czesław Bem and Kazimierz Szpilman; violinists Adam Dobrzyniec (Stanisław Dobrzyniec, also a violinists, was on the „Aryan side”), Henryk Fiszman, Artur Flatau, Jakub Szulc, Józef Waghalter and Ignacy Mitelman; trumpet player and conductor Adam Furmański; violinist and conductor Ludwik Holcman (the concertmaster in the years 1937–1939); bass player Józef Łabuszyński; cellist, chamber musician, composer and conductor Marian Neuteich; composer, pianist and conductor Bronisław Wolfstahl (all of the aforementioned musicians, maybe apart from Mitelman, died) and many others, whose names were not listed in the chronicles. In the beginning, the orchestra comprised 66 musicians, but later more than 80 people.

Big contribution to the orchestra was made also by Szymon Pullman, eminent violinist and conductor, his relative Izrael Hamerman (both of them died in Treblinka) and Henryk Waghalter (who also died even though he was in hiding in one of the Catholic churches on the territory of Warsaw). Many, eminent soloists collaborated with the orchestra, inter alia, winners of the Chopin Competitions and the Henryk Wieniawski Competitions.

Even though it was not possible to establish names of all members of the orchestra, we have a lot of information about their activity and repertoire. Gazeta Żydowska (printed in Polish), published in the ghetto with consent, or rather on the initiative of the occupier, regularly printed reviews of concerts.

The symphonic repertoire was determined by many factors. Actually, the occupier allowed to play only „Jewish” music, for example Halevy, Bizet, Offenbach, Meyerbeer, Mendelssohn, Mahler, a rule which was anyway disobeyed, and departures from it, strangely enough, initially tolerated by the authorities.

Musicians in the ghetto did not have many musical scores, there were no scores written for voices. The orchestra also lacked members, especially in terms of brass instruments. As a result, it was necessary to make many adjustments to the works of the composers from the Classical and Romantic periods by exchanging, according to reviewer Aleksander Rozensztejn, „noble, Romantic sound of a French horn with... a bit bright and shallow sound of a saxophone. However, an intelligent but sensitive listener accepted this adjustment as a necessity of extraordinary conditions” (Gazeta Żydowska, 29.06 1941).

The first symphonic concert in the ghetto took place on 25th November, 1940 in a room of the Judaic Library at 5 Tłomackie (currently the edifice of the JHI). The program included works of Beethoven: Coriolani Piano Concert, Es-dur (soloist Ryszard Spira), overtures to Auber’s The Dumb Girl of Portici and Grieg’s Peer Gynta. It was conducted by Marian Neuteich. Beethoven belonged to one of the composers played most often. The next concerts included overtures Egmonti Leonora III, symphonies I, III, V, VIII and also, which was not written in the reviews, but is mentioned by Professor Ludwik Hirszfeld in his History of one life (p. 369), IX Symphony: „The atmosphere at the concerts was also strange. The Jews were not allowed to play other musicians than Jewish. But these spiteful Jews loved also Beethoven and Brahms and Chopin and they would rather risk being imprisoned than give up this eternal beauty. I even remember Beethoven’s IX, Ode to Joy, played by the convicts. Because it boggled those spiteful Jewish minds that it was even possible to really forbid them to enjoy the beauty which is nobody’s possession. To forbid someone to listen to Beethoven is like forbidding them to enjoy the sun...”

ŻOS’ concerts took place in various rooms: in a room of „Femina” theatre (today there is a cinema in this place bearing the same name), in a room of „Melody Place”, in a room of „Gospoda (6 Orla Street), and also in Janusz Korczak’s Orphanage. Part of the revenue was given to charity, poor music lovers were given free tickets to the concerts.

With time, the situation of ŻOB started getting worse. Since the beginning of 1942 the occupational authorities began categorically forbidding performing „non-Jewish” music. There were more arrests and transfers of musicians. Some musicians, thanks to help of their Polish friends, escaped the ghetto and were in hiding and therefore survived (inter alia Władysław Szpilman, Hanna Dicksteinówna). The Nazis requisitioned instruments and used all forms of persecution. Useless were Czerniaków’s interventions that since then only pieces of composers from the infamous lexicon Die Juden in der Musik would be performed.

On 12th April, 1942 took place the last symphonic concert which included not only pieces of Mozart, Paganini, Weber and Mendelssohn but also Karol Szymanowski’sThe Arethusa’s fountain performed by violinist Henryk Reinberg. According to the audience of the ghetto concerts, Polish music — unannounced — would normally appear during encore...

In mid 1942, the musical life of the Warsaw Ghetto died completely. Its last chord was an event on 1st July, 1942 when Head of the Community Adam Czerniaków called a meeting, which was attended by a few hundred leading representatives of the Jewish community. After a shocking speech, openly describing the situation of the Jews — also eminent scholars and artists — there was a tea break. Professor Ludwik Hirszfeld also remembers this event. „There were a few hundred people present [...] During the meeting, a Gestapo man came into the room [...] During the break, it was an unforgettable moment, piano music started playing, a mix of Chopin’s preludes and chords of „Poland has not yet perished.” The Jews were not allowed to play pieces by non-Jewish musicians. The fact of playing Chopin at an official meeting had a special meaning. But I would also like to say it to the future generations that at this last official meeting of the community they played „Poland has not yet perished”. For doing so both the artist and the chairperson as well as the majority of the people present there could have been taken to a concentration camp. But I can assure you that I did not see any hesitation in the eyes of those present, on the contrary, the song was a sign of hope and gratitude.”

On 22nd July, 1942 the Great Deportation of the Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka began. The Head of the Community, Adam Czerniaków, refused to sign an ordinance saying that everyday between 6 and 10 thousand people should be delivered to the Umschlagplatz so that they could be transferred to Treblinka; shortly after that he committed suicide. Among more than 350 thousand Jews and people of Jewish descent taken to the gas chambers in Treblinka were also musicians of the Jewish Symphonic Orchestra.