- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

We don’t know his date of birth. Nechemiasz Tytelman was an activist of Poale Zion-Left and one of the leaders of the „Sztern” (Star) sports club.

We know that he was a candidate to the council of the City of Warsaw from the Jewish Workers’s Election Committee – Poale-Zion. [1] Kassow writes that just before the war, Tytelman had a breakdown, but then, once he recovered, he became an active member of resistance in the ghetto. [2]

From Tytelman’s diaries we learn that in 1939, he escaped to Russia and returned to Warsaw in May 1940. In the ghetto, he lived at 31 Muranowska street. He continued his activity in the party, distributing confidential radio messages, and in 1941, together with Natan Ostrowicz, he was organizing political groups which later joined the „groups of five” in the Antifascist Bloc.

For Oneg Shabbat, Tytelman was working on reports, for example on situation in Łomazy, Biała Podlaska, Vilnius. He was receiving a small payment for this work – his name appears in the Accounting book 10 times. He was also the author of a study about the Job Office in the Warsaw Ghetto. He was signing his writings as N.R. Or N. Rocheles (Natan Rocheles – Natan son of Rachela). He was writing in Yiddish, using ink, making copies and signing his works, which makes them easier to identify.

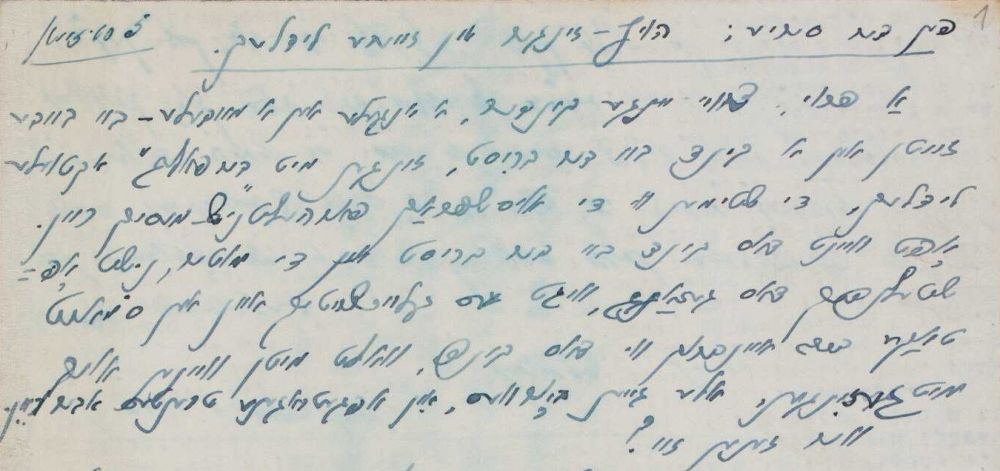

![tytelman_4_dziennik.jpg [209.44 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/23/fbd4fe46130b1bd9c6aca57d2cc5544e/jpg/jhi/preview/tytelman_4_dziennik.jpg)

Tytelman’s most important contribution in the works of Oneg Shabbat was collecting folklore of the ghetto (along with rabbi Szymon Huberband). He was roaming the streets with pen and paper [3], writing down anecdotes, riddles, jokes, sayings, lyrics of popular songs performed by street singers. A large part of this folklore collection documents the jargon and customs of smugglers. Many jokes and anecdotes referred to head of the Judenrat Adam Czerniaków and the administration of the „Community”. Tytelman often added an interesting description of the performer and his story.

Even though before the war his writing activity was limited to reports from sports events, he decided to document the folklore of the ghetto under the influence of Szmuel Lehman, one of the pioneers of Jewish folklore studies. He asked Tytelman – for the last time on his death bed – to write down everything he’s got, it may even look awkward, in all possible versions. [4]

The most popular songs by street singers were Mues (Money) and Di Bone (Food stamp). The first one was sang by actor Bolesław Norski-Nożyca in the Eldorado theatre at Dzielna street.

One of the best sources of information about street songs was Jankew Lejb Solnicki, a boy looking 13-14 years old [he was really 16], with small but nice voice, already with a hoarse voice from exploiting his throat too much. This boy, barefoot and dressed in rags, was really pretty despite this. His bright face and beautiful eyes stood out among the rags. [5] He was the son of Tytelman’s friend, Abraham Solnicki, who died due to dysentery (the boy’s mom, Chaja Landau, fell victim to famine). He was wandering through the ghetto, looking for food leftovers in bins, singing songs, and people were giving him small money. Tytelman invited him to his house which allowed him to write down the lyrics of the songs sang by the boy.

I took him home. It was raining heavily. Small, like a wet kitten, he was all shaking. (…) The boy doesn’t seem to be dulled at all. He knows what he’s saying. Seeing that I’m writing down songs, he paid attention to the fragments I’ve missed, reminded me to write the chorus etc. [6]

Money, money

You have no money, but don’t worry

take Pinkiert’s box and lay down in it

Chorus: Money, money is the best thing

The boss’s wife can afford a perm

But children go to sleep without a meal

Chorus: Money, money is the best thing (…)

Tytelman was also talking to 12-year old Mojsze, who was working to support his parents and siblings. He provided words to „The camp song”. 10-year old Szłojme Wadowski was wandering through the ghetto with his 13-year old sister Chana. He, a small creature looking like he’s only a few years old, is neatly dressed, his sister – wrapped in rags. When their parents died, they stayed with their cousin, but had to work to support themselves and their younger siblings. The boy was singing a song „Russian village”, and the girl was trying to ask for food.

![tytelman_1_piosenki_dzieciakow_2t.jpg [134.99 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/23/1bbc4d829d9350390a248c3fb87f5080/jpg/jhi/preview/tytelman_1_piosenki_dzieciakow_2t.jpg)

Tytelman was also writing his Diary -preserved notes from 14 and 16 May 1941 convey the moods in the Warsaw Ghetto due to the war developments. The notes are built on a similar pattern – information from radio monitoring (Rudolf Hess’s escape to Great Britain, Goering’s death) make people smile, but going out onto grey, dangerous street brutally verifies the gossip and stifles enthusiasm. For most people, the immediate reality – hunger, cold and tiredness is the most important. The streets are devoid of hope.

An especially valuable collection are Current conversations (jokes and humor). Wartime jokes, Songs and Street propaganda, collected by Tytelman in June 1942 – a month before the Grear Deportation.

Jokes: Food stamps, additional cards, work card, accommodation card, card to the workshop and kennkarte… how many more cards does he [the German] need to kill me? [7]

It’s better that Hitler is in my fur than me in his skin. [8]

Unfortunately, these aren’t jokes: How were two Jews shot today at Bagno street? They had an argument, one shouted: bandit, the other called him a killer. The policeman decided it must have been about him… [9]

Song: Haman (melody: Riwkele-Rebeka – most likely, The Rebeka tango, composed by Zygmunt Białostocki in 1933) [10]

There used to be a time

when Jews lived like kings,

happily and well.

They knew no unhappiness,

didn’t think about what may happen

tomorrow or sometime in the future.

The Jews lived

in happiness and peace.

But what happened suddenly?

A real catastrophe!

The life has stopped

since Haman is in power.

![tytelman_2_Piosenki2.jpg [224.35 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/23/40b706138c8b45a2ac4cbacf4f6ce438/jpg/jhi/preview/tytelman_2_Piosenki2.jpg)

Street propaganda: After the campaign to take away furs, small posters appeared on streets of Warsaw. They showed Hitler on twisted skis, in caracul ladies’ coat with a fox collar. On his back, there was a small „gipsy stove” with smoke coming out of it. The caption in Polish said: „even this won’t help you”. [11]

After withdrawal from Moscow, walls and pavements were covered with „1812” written with paint of chalk.

Recently, captions on street lamps and posts appeared: „reserved – only for Germans”. [12]

According to several sources, Tytelman was thought to be saved from Umschlagplatz by a boxer from the Star club, Szapsa Rotholc, after the war accused of collaboration with the Germans. [13]

Nechemiasz Tytelman was killed in the ghetto in 1943. Circumstances of his death remain unknown.

Mieczysław Szymkowiak in his articles from the „For the price of life – the capital city” (1959-1960) mentions Dawid Tytelman, but according to the context, we may assume he confused the name and the excerpt refers to Nechemiasz Tytelman:

During the Ghetto Uprising, groups of sports activists were helping the insurgents, delivering arms, medication, food. In the last stage of the struggle, activists offered their colleague Dawid Tytelman, member of the Sports Clubs Workers Unions and vice-chairman of the Star sports club, escaping the ghetto through the canals. The possibilities were limited, only several people could have been rescued every day. Tytelman was postponing his escape, finding dozens of people to leave first. Strong protests from colleagues on the „aryan side”, who wanted a respected activist to join them, didn’t work. He was responding with the same line: „are the people I’m sending to you any worse than me?”, and added even more names of people to be rescued. „I will make it, but I cannot leave my people”. He didn;t make it and died like a hero, like a captain of a sinking ship. [14]

Written by: Anna Majchrowska

Translated by: Olga Drenda

Footnotes:

[1] http://kpbc.umk.pl/Content/205721/DZS_POPC003_029_10.pdf

[2] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017, p. 316.

[3] Ibidem.

[4] Introduction [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, vol. 26, ed. Agnieszka Żółkiewska, Michał Tuszewicki, JHI, Warsaw 2017, p. XXXII-XXXIII..

[5] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzieci – tajne nauczanie w getcie warszawskim, ed. Ruta Sakowska, vol. 2, JHI, Warsaw 2000, p. 152.

[6] Ibidem, p. 153.

[7] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, op. cit, p. 746.

[8] Ibidem, p.754-756.

[9] Ibidem, p. 746.

[10] Melody: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aocFiuR1_TU; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xE9KtUEGs_E)

[11] Ibidem, p. 751.

[12] Ibidem.

[13] https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/1946-polish-jews-expel-collaborator-1.5427199

[14] Mieczysław Szymkowiak, Warszawski sport w podziemiu [in:] Za cenę życia, http://pilkajestpiekna.pl/index.php?typ=pjp&id=179

Bibliography:

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Utwory literackie z getta warszawskiego, vol. 26, ed. Agnieszka Żółkiewska, Michał Tuszewicki, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Dzieci – tajne nauczanie w getcie warszawskim, ed. Ruta Sakowska, vol. 2, JHI, Warsaw 2000.