- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

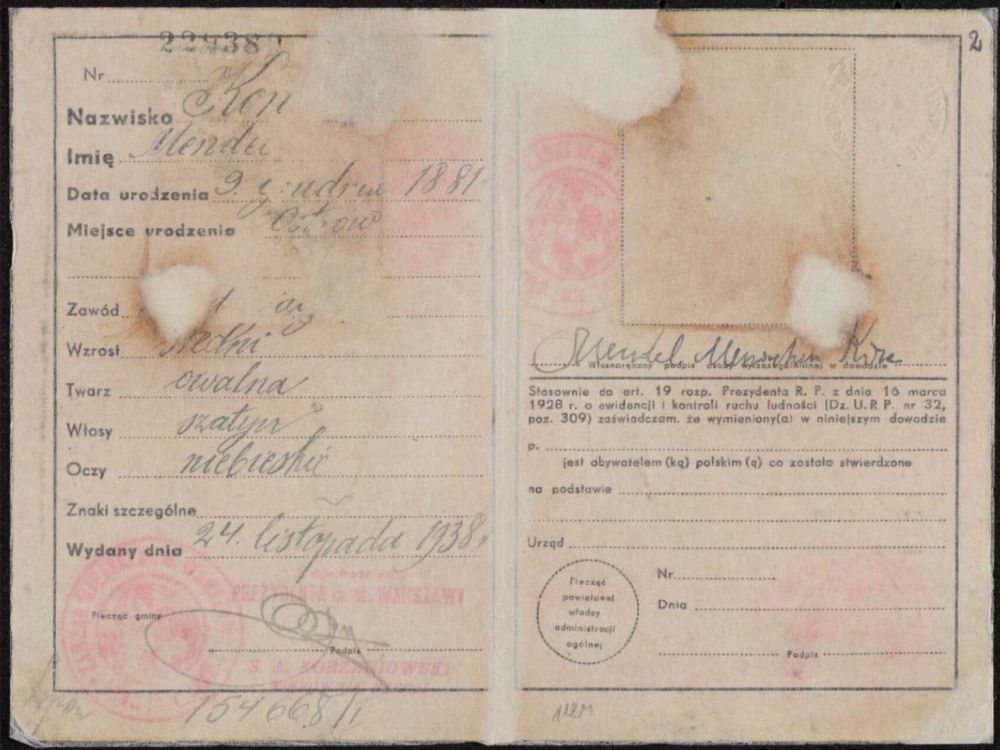

Menachem Kohn’s 1938 ID card / The Ringelblum Archive, ARG I 1420

‘Esteemed and extraordinary’

Menachem Mendel Kohn (Kon) was born in 18811 in Ostrów (probably today’s Ostrów Mazowiecka). He became a wealthy merchant and lived in Ostrołęka. When the World War II began, he came to Warsaw along with other refugees2. Kohn worked in the Jewish Social Self-Help, encouraging his co-workers to raise as much money as possibly to aid the poorest occupants of the ghetto3. There he met Emanuel Ringelblum. He participated in the founding meeting of the Oneg Shabbat group in Ringelblum’s apartment in the autumn of 1940 and became the group’s treasurer4. The accounting books he was responsible for from autumn 1940 until August 1942 remains the only one large document of this kind left of the Oneg Shabbat group – a source of information on its activity day by day, with an index of contributors5.

Kohn not only belonged to the strict leadership of Oneg Shabbat6, but also supported the Archive financially with his own money7. He was responsible for collecting funds for the group’s basic functioning, which included ‘paper and stationery, payments for writings, money to buy food and medicine for the key members of the project’8.

![kohn_ksiega_kasowa_16-75.jpg [157.09 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/fb930d5a31daaa0afafc64bbf30d6b59/jpg/jhi/preview/kohn_ksiega_kasowa_16-75.jpg)

One of cards from Oneg Shabbat accounting book run by Menachem Kohn,

showing expenses in July 1941. Bottom right top shows the surname of Ringelblum

The Ringelblum Archive, ARG II 1

Aside from accounting, Kohn was collecting and sharing financial aid among those Oneg Shabbat contributors who had found themselves in an especially difficult situation. Emanuel Ringelblum called him ‘a dedicated father and a caring guardian’ of the brotherly community which was Oneg Shabbat9. In May 1942, Hersz Wasser was worried about Kohn’s health, explaining that without him, the Archive would burst like a bubble10. The Archive contains messages from people saved by Kohn from typhus or death from famine11:

‘Our esteemed friend, an extraordinary man, who has always loved his nation and his people endlessly, dedicating his own blood and soul to them, Sir Menachem Kohn, son of Miriam, may the Omnipresent help you!’12

‘A man of great respect, outstanding among the crowds, esteemed and extraordinary, may the Eternal guarantee you health forever!’13

‘Honourable Mr Kon! May you be granted most precious blessings! May the fact that you have brought back to life 70 souls, who were already condemned to death, bring you satisfaction (…)’14.

![kohn_zaproszenie.jpg [391.94 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/1182f6c56970f786729b63037c54a845/jpg/jhi/preview/kohn_zaproszenie.jpg)

An invitation for Menachem Kohn to ‘School morning’

– a performance by children from the School Department of the Jewish Council,

in the ‘Femina’ theatre, on May 5, 1942.

At the time, Kohn lived by the now non-existent Przebieg Street, at No. 2

The Ringelblum Archive, ARG I 1421

Among the people he saved were Perec Opoczyński and Szymon Huberband. When they contracted typhus, Kohn managed to organize expensive medicine and extra food rations which helped them recover15. Huberband was Kohn’s best friend. This young rabbi and amateur historian, who lost his entire family in 1939 in a German air raid, became Oneg Shabbat’s valuable contributor. He collected information about persecutions of Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto and in towns in the Warsaw area, like Otwock or Grodzisk, about the destruction of synagogues and Jewish culture by the Germans. When Huberband was deported to Treblinka in August 1942, Kohn wrote a memorial note in which he called him ‘a person pure like a crystal’, swearing to remember him and to take revenge on his killers16.

Aside from taking care for financial matters, Kohn was also contributing to the Ringelblum Archive. It was probably him who delivered a report called My visit in the ghetto prison, dated 25 May 1942. The Jews who attempted to trespass the ghetto walls in search for food were imprisoned in the crowded cells of the Gęsiówka prison at 22 Gęsia street. Most of them were sentenced to a slow death from famine, tuberculosis and typhus.

The deportation diary

Kohn left a diary from the period of the Great Deportation in the summer of 1942, during which about 300,000 people from the ghetto had been sent to Treblinka. He described the terror and loneliness in the ghetto being systematically destroyed by the Germans. In panic, which spread among people in the closed district, he tried to hide in the workshop ran by Aleksander Landau, a member of Oneg Shabbat. His former friends, who decided to fight for their own lives, blocked his way to this seemingly safe hiding place (employees of workshops were, for a certain period of time, not in danger of deportation).

‘It is so difficult to write when one is stuck in a nightmare, chased by wild beasts, who try to break you to pieces with machine guns or suffocate you with gas’ – wrote Kohn. – ‘I will make an attempt at least, perhaps I will manage to describe at least a small part of what I saw and experienced, so that the wide world reads and knows how to take revenge on these bloodthirsty sadists for everything they did to us Jews in Poland, especially in Warsaw’17.

![Kohn_pierwsza_karta_dziennika.jpg [175.88 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2022/3/24/cac68eb2851be743aa0a84d9806a085b/jpg/jhi/preview/Kohn_pierwsza_karta_dziennika.jpg)

Menachem Kohn, fragment of the first page of the diary

kept during the Great Deportation, August 6, 1942 / The Ringelblum Archive, ARG II 249

‘We were crawling on all fours to basements, into the rubble, trying to hide from bullets. We spent the night lying down looking death in the eyes and listening to the noise of trains carrying today’s victims to Treblinka death camp. The very memory of them will disappear by tomorrow. Tomorrow, we will share the same fate. We have spent the entire night in this horror’18.

Kohn had survived the Great Deportation. Afterwards, he became the leader of a committee which funded Jewish activists’ escapes from the ghetto and helped them find accommodation on the ‘Aryan’ side19. When the Jewish Combat Organization was established, he also joined a committee collecting money for the JCO20. When Rachela Auerbach and Emanuel Ringelblum left the ghetto in February 1943, only five members of Oneg Shabbat leadership remained behind the walls – Hersz Wasser, Eliasz Gutkowski, Izrael Lichtensztejn, Szmuel Winter and Menachem Kohn. They kept gathering resources to the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto until the uprising broke out. Kohn was employed then in Brauer’s workshop at 32 Nalewki street, repairing damaged German helmets and uniforms. He died after the beginning of the uprising, in April 1943.21

Sources:

Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 7, Spuścizny, ed. Katarzyna Person, transl. Sara Arm and others, Wydawnictwo ŻIH/Wydawnictwo UW, Warsaw 2012.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 11, Ludzie i prace „Oneg Szabat”, ed. Aleksandra Bańkowska, Tadeusz Epsztein, transl. Sara Arm and others, Wydawnictwo ŻIH/Wydawnictwo UW, Warsaw 2013.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 12, Rada Żydowska w Warszawie (1939-1943), ed. Marta Janczewska, transl. Piotr Kendziorek, Sara Arm, Wydawnictwo ŻIH/Wydawnictwo UW, Warsaw 2014.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 23, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, ed. Katarzyna Person, Zofia Trębacz, Michał Trębacz, transl. Sara Arm and others, Wydawnictwo UW/Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2015.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 32, Pisma rabina Szymona Huberbanda, ed. Anna Ciałowicz, transl. Anna Ciałowicz, Magdalena Siek, Wydawnictwo ŻIH/Wydawnictwo UW, Warsaw 2017.

Samuel D. Kassow, Kto napisze naszą historię? Ukryte Archiwum Emanuela Ringelbluma [Who Will Write Our History?: Rediscovering a Hidden Archive from the Warsaw Ghetto], transl. Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2017.

Footnotes:

1 Basic information after: Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 7, Spuścizny, ed. Katarzyna Person, transl. Sara Arm and others, Wydawnictwo ŻIH/Wydawnictwo UW, Warsaw 2012, p. XVII.

2 Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 12, Rada Żydowska w Warszawie (1939-1943), ed. Marta Janczewska, transl. Piotr Kendziorek, Sara Arm, Wydawnictwo ŻIH/Wydawnictwo UW, Warsaw 2014, p. 221, footnote 510.

3 Samuel D. Kassow, Kto napisze naszą historię? Ukryte Archiwum Emanuela Ringelbluma [Who Will Write Our History?: Rediscovering a Hidden Archive from the Warsaw Ghetto], transl. Grażyna Waluga, Olga Zienkiewicz, Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2017, p. 277.

4 Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 11, Ludzie i prace „Oneg Szabat”, ed. Aleksandra Bańkowska, Tadeusz Epsztein, transl. Sara Arm and others, Wydawnictwo ŻIH/Wydawnictwo UW, Warsaw 2013, p. XXIII; p. XXIV, footnote 29.

5 Ibidem, p. XXVIII.

6 Ibidem, p. XXIV-XXV.

7 S. Kassow, op. cit., p. 276.

8 Ibidem, p. 382.

9 Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 7, Spuścizny, op.cit., p. XVII.

10 After: ibidem.

11 Ibidem, p. 350-356.

12 Ibidem, 350.

13 Ibidem, p. 351.

14 Ibidem, p. 352.

15 S. Kassow, op. cit., p. 276.

16 Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 32, Pisma rabina Szymona Huberbanda, ed. Anna Ciałowicz, transl Anna Ciałowicz, Magdalena Siek, Wydawnictwo ŻIH/Wydawnictwo UW, Warsaw 2017, p. 287-288.

17 Archiwum Ringelbluma, vol. 23, Dzienniki z getta warszawskiego, ed. Katarzyna Person, Zofia Trębacz, Michał Trębacz, transl. Sara Arm and others, Wydawnictwo UW/Wydawnictwo ŻIH, Warsaw 2015, p. 414. A note from early September 1942.

18 Ibidem, p. 415. A note from 6th September1942 r.

19 Ibidem, p. 199.

20 S. Kassow, op. cit., p. 582-583.

21 Ibidem, p. 279.