- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

On 9th January, 1970, in London died Mieczysław Grydzewski. He was born 75 years and 13 days earlier in Warsaw. Meanwhile, in 1920, he founded, edited and published a literary magazine „Skamander”, serving as a platform for a few young poets who quickly became the most important artists of the generation: Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, Jan Lechoń, Antoni Słonimski, Julian Tuwima and Kazimierz Wierzyński. A couple of years later, Grydzewski created a weekly „Wiadomości Literackie” [Literary News], at the time one of the most influential, interwar social-cultural magazines, where the leading role was played by these same five poets, supported by another wordsmith, Boy-Żeleński.

Grydzewski was the organizer of a new age — remembered Marian Hemar — at the time, he created something which is always the hardest to create in literature, always most precious and valuable: he created a circle. He turned a group of acquaintances into friends, friends into a poetry cartel; he bonded them with a community of fame, which he assigned to everyone.

Co-workers of „Wiadomości” regarded their editor as a liberal-despot. Liberal in terms of his political views and a despot at work. He edited on his own, his flat at 8 Złota Street in Warsaw serving him as an office. He would thoroughly correct received manuscripts disregarding protests of their authors. Grydzewski, taking care of the issues concerning „Skamander”, „Wiadomości”, and also other magazines, such as „Przyjaciel psa” [A dog’s friend], being himself the most faithful friend of these animals, would work almost non-stop. Malicious rumors say that even when he went to a brothel in Paris, he would take with him a pile of texts. He was unbelievably conscientious. „Me,” he used to say, „when I am to quote ’Poland has yet not perished’, I check in advance.”

The greatness of Grydzewski was not due to his editorial skills, which sometimes were rather peculiar, for example, in some texts he would erase all commas before „że”. Grydz, as his friends used to call him, could excellently turn a text into a coherent whole. And in the case of „Wiadomości” it was especially difficult because of its eclectic nature — both in terms of the type of printed materials (on one hand poetical, but also Bruno Schulz, a prose writer, made his debut there) and aesthetic and political views of the authors. The published texts were written by both the liberal Skamandrites and, critical towards them, theoreticians of avant-garde, or Adolf Nowaczyński, supporting the National Democracy.

Grydzewski, similarly to a vast majority of his co-workers, belonged to the group of the most eminent Polish intellectuals of Jewish decent. And also as them, because of his decent, he was attacked by the National Democracy and as a result „Wiadomości”, edited by him, was considered to be of „non-Polish spirit”. The editor, on the contrary to Tuwim or Słonimski, however, did not engage himself in journalistic fights with the anti-Semites. Generally, he did not write much, claiming that he did it worse than what he demanded from the others. It seems that he also maintained bigger distance from the National Democratic witch-hunt against „Wiadomości” than others. He is famous for his humorous saying that it is not without reason that his magazine is labelled „żydokomuna” since „the editor was of Jewish descent. Communism, however, was represented by the secretary of the editorial board [Władysław] Broniewski.”

After the German invasion on Poland, Grydzewski decided to flee the country, not wrongfully suspecting that he would be one of the first people arrested by the occupier. He managed to cross the border with Romania and then got to France. When seven months later Hitler began the Battle of France, Grydzewski left for England. Still during his stay in France, the editor began publishing wartime version of „Wiadomości Literackie, „Wiadomości Polskie”, the activity which he resumed immediately after arriving to Great Britain. The editorial board had a negative attitude towards the politics of the Polish government in exile and the British government, what took severest form when the Sikorski–Mayski Agreement had been signed. As a response to the criticism of the actions of both governments towards the Soviet Russia, the British authorities cut the subvention of „Wiadomości”, which as a result had to limit its activity. Finally, the magazine closed at the beginning of 1944, shortly after the time when Grydzewski and other journalists collaborating with him took an uncompromising stand on the case regarding the question of responsibility for the Katyń massacre.

A year after the war, the indefatigable editor managed to resume publishing of the magazine, this time with a shortened title „Wiadomości”. „Wiadomości” continued expressing opinions of negative attitude towards any compromises with Russia. They also saw a gloomy picture of the post-war Polish reality and very negatively judged decisions of those intellectuals who decided to come back to Poland. For Grydzewski, especially painful was the fact that it was his two former friends, Julian Tuwim and Antoni Słonimski, who had done it. Particularly because Tuwim got deeply engaged in legitimization of the system imposed on Poland.

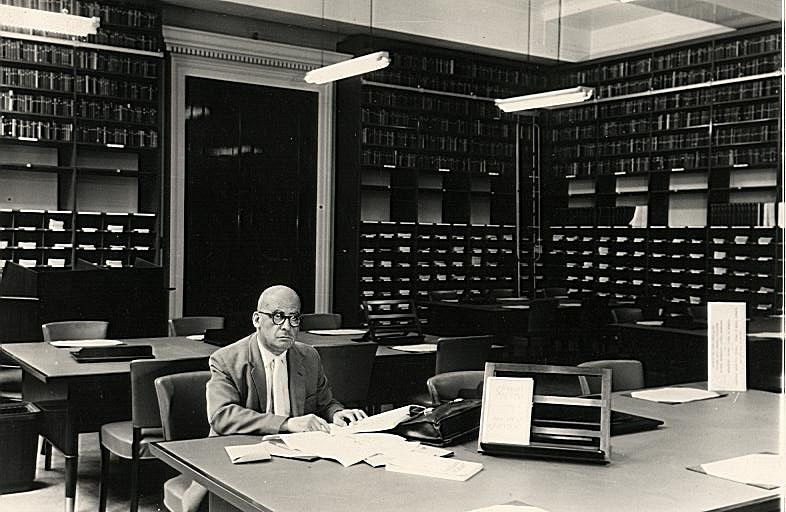

Only in London was Grydzewski able to pluck up his courage and begin writing his own texts. He ran a column titled Silva rerum [From Latin — forest of things], where he published spice concerning Polish history and literature that he found in the library of the British Museum. He did it, however, under a pseudonym, sometimes polemicizing with... editor in chief Meczysław Grydzewski. In his texts, Grydzewski would often bring up the Jewish subject matter. In the 1960s, so in times when the Judenrat appointed by the Germans in the ghettos was commonly considered to be collaborationist institution, which immensely contributed to the extermination of the Jews, Grydzewski defended Adam Czerniaków. But he also wrote on lighter subjects. In an anecdotal form, he pondered, for example, on the mood in which the author of „the Nutcracker” must have been when as a Prussian official in Warsaw he was giving surnames to the Polish Jews — sometimes they were lyrical, as those inspired by names of birds or flowers, and sometimes, when translated into Polish, malicious like those: „Rybojad” [Fisheater] or „Paniedopomóż”[Godhelpus].

In private conversations conducted in exile, Grydzewski would sometimes dismay his acquaintances claiming that in pre-war Poland there had been no anti-Semitism. It was especially bizarre as he himself had sometimes been the object of hateful attacks. This specific „memory lapse” could have been a manifestation of his strong aversion to communism, implemented in Poland by force, sometimes presented as a remedy for national antagonisms digesting Eastern Europe. And as there were no symptoms of the illness — Grydzewski seemed to claim — then not only was the remedy not needed, but it could even do more harm.

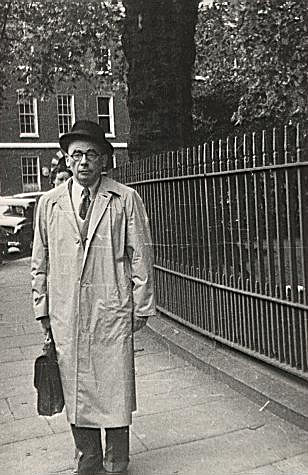

„Wiadomości” were published until 1981 and they outlived its founder by 11 years. Grydzewski had to resign from editing a few years earlier due to partial paralysis. Till his death, he had a financial support of his friends and readers from all over the world. He died in a clinic outside London. Today, even though the editor used to sit with the Skamandrites at the same table on a floor in Ziemiańska, he is seen as a less colorful character than them; actually, he is almost forgotten. Józef Wittlin, however, is right writing that Grydzewski was not a person but institution — paraphrasing a saying by Louis XIV, the legendary „Wiadomości Literackie” was him.