- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

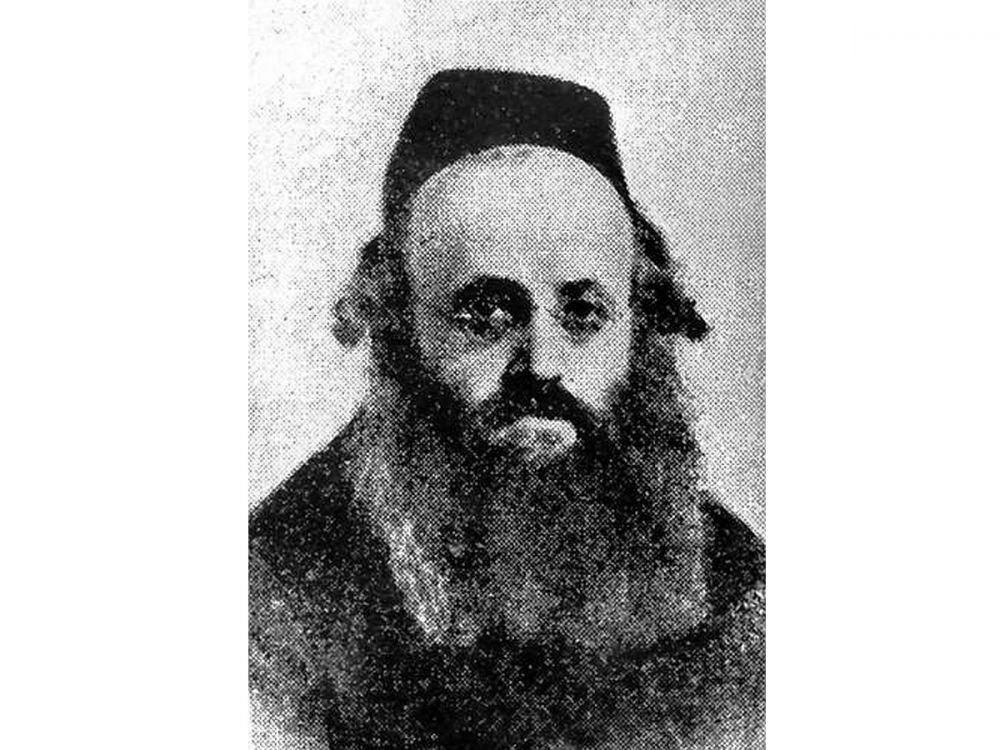

Kalonymus Kalman Shapiro

Kalonymus Shapiro was born on 20 May 1889, most likely in Grodzisk Mazowiecki. He was born into the great Hassidic families. He received his name after a great forefather, Kalonymus Kalman Ha-Lewi Epsztejn from Kraków. Kalonymus’ mother – Chana Bracha Szternfeld-Horowic – was serving the Lord with her heart and soul throughout her entire life, pushing away or even neglecting her own needs in order to raise her sons to manifold [their service]. [2]

His father, rebbe Elimelech of Grodzisk (1823–1892), was a rabbi and a spiritual leader of Grodzisk Hassidim. He dedicated a lot of attention to his son, especially when he developed scarlet fever and his life was in danger. He died when Kalonymus was three years old. I was a small boy when I became orphaned. I have hardly known my righteous father – I was never given the chance to be brought up by this saintly man of God. [3]

As Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska writes, he was studying the Torah already as a child, he had a contemplative nature, kind and sympathetic towards others. [4] He was a student of rabbi Jerachmiel Mosze Hofsztejn from Kozienice, a descendant of the Great Magid, who taught him the art of circumcision and to play violin. At the age of 15, he married Rachel Chaja Miriam Hofsztejn, the daughter of Jerachmiel Mosze, who was respected among the Hassidim, studied the Torah and Hassidic books. They had two children: son Elimelech Ben-Cijon, an expert on the Torah, and daughter Rechil Ester (Jehudis).

After the death of Jerachmiel Mosze in 1909, he became the Admor (a title given to tzaddiks), and in 1913, he took the position of a rabbi in Piaseczno. When the World War I began, he moved to Warsaw, remaining in position of the rabbi in Piaseczno, where he would spend every summer. His house was located at 15 Niecała street.

In 1923, together with a group of his spiritual followers, he established a yeshiva in Warsaw named Da’at Moshe (Hebr. The Faith Of Moses). It was one of the largest Jewish academies in pre-war Warsaw, with about 300 students. It was managed by rabbi Kalman Huberband, a stepbrother of Szymon Huberband, an Oneg Shabbat associate.

Under the auspices of the yeshiva, in 1932 Shapiro released a textbook The Student’s Duty (Hebr. Chovas ha-talmidim), which quickly gained respect in Poland and abroad. He promoted a method of modern teaching of the Hassidic youth, according to which the teacher was supposed to adjust his language to students’ possibilities, operate images and parables. The message should be positive, inspiring spiritual potential in the students – to wake their souls through service to God. [5] The task of the teacher is to help the student to enter the path of discovering their own greatness [6] hence he should avoid talking about punishments which await the apostates. Shapiro also wrote a guide, Followers of the good thought (Hebr. Bnei Machshava Tova), which wasn’t printed – it was available only to certain students. This work was finally published in Israel many years after the war.

Shapiro was supportive of Orthodox settlements in Palestine (his brother Yeshayahu Shapiro settled in Eretz Israel in 1920, and Kalonymus boughtland there), he also joined the Agudat Israel party. Rabbi Shapiro was also interested in biomedicine, advising medication, therapy, visiting doctors. His advice was highly respected, not only among the Jewish community. According to legends, his prescriptions in Latin were allegedly functioning in Warsaw pharmacies [7], yet the most likely veriosn is that his name cards were taken for prescriptions.

On 19 June 1937, rebbetzin Rachel Chaja, Shapiro’s wife, who he had a strong emotional bond with, died. Her death had left a strong impact on him. He wrote: She was extraordinarily righteous, her qualities were noble, and her fair, kind acts went beyond her possibilities; they were a delight for her soul. She was like a merciful mother to the embittered in general, but especially for the faithful and for the sons of the Torah. [8]

When the World War II broke out, he was in Piaseczno. Not wanting to leave his students, he returned to Warsaw. On 25 September, his son Elimelech Ben-Cijon Szapiro was injured in the bombing of Warsaw and transported to the Red Cross hospital. When rabbi and his family were reciting psalms in front of the hospital, another bomb killed several people, including Shapiro’s wife Gitl Shapiro, the daughter of rebbe from Bolechów from the Karlin dynasty, his brother’s wife, and a group of students. The rabbi survived only because he went looking for a doctor with a group of Hassidim. Elimelech died on 29 September 1939. [9] Less than a month later, on 20 October, the rabbi’s mother passed away. Deeply impacted by the war already in its first months, the rabbi didn’t give up his mission, remaining patient and humble. [10]

After 16 November 1940, the 5 Dzielna house, where the rabbi lived, had found itself within the borders of the Warsaw Ghetto. It became a place of meetings, learning and prayer. The rabbi would welcome there refugees, mainly from Piaseczno and nearby; he also organized a soup kitchen for people suffering from hunger (managed by the Joint Distribution Committee). He was also giving his weekly commentaries to the readings from the Torah.

Kalonymus Shapiro’s legacy in the Ringelblum Archive

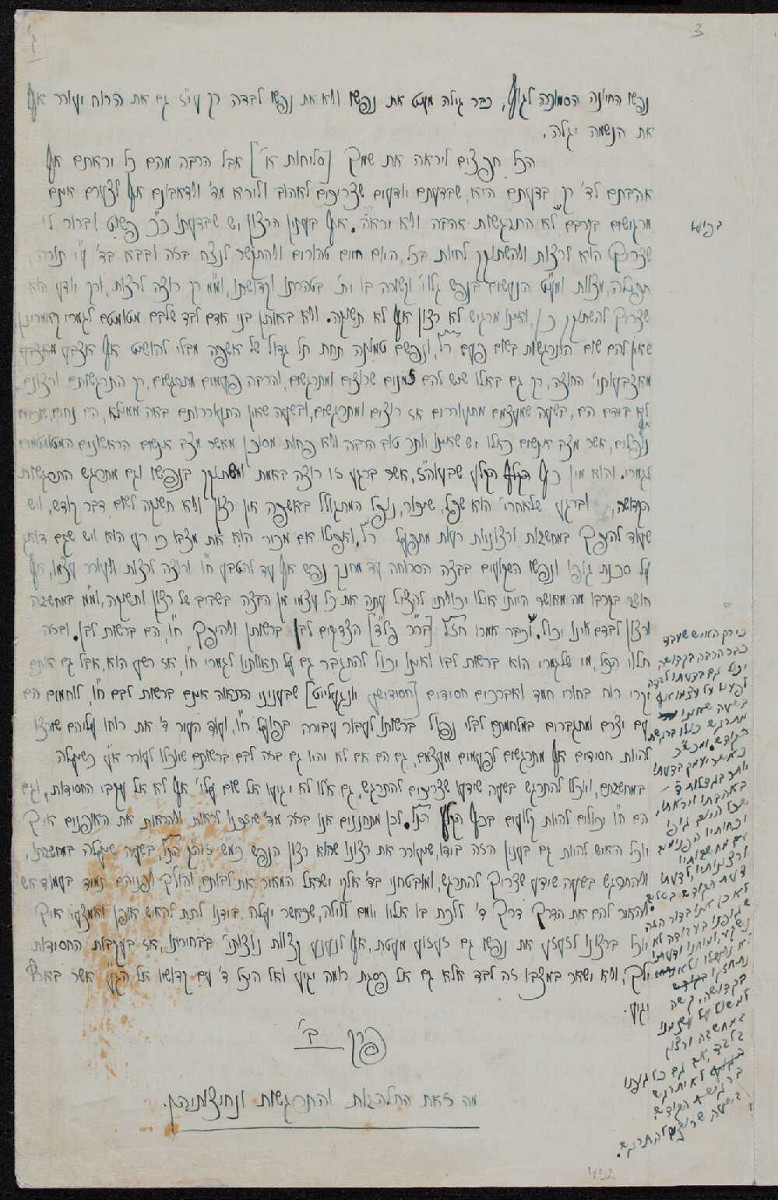

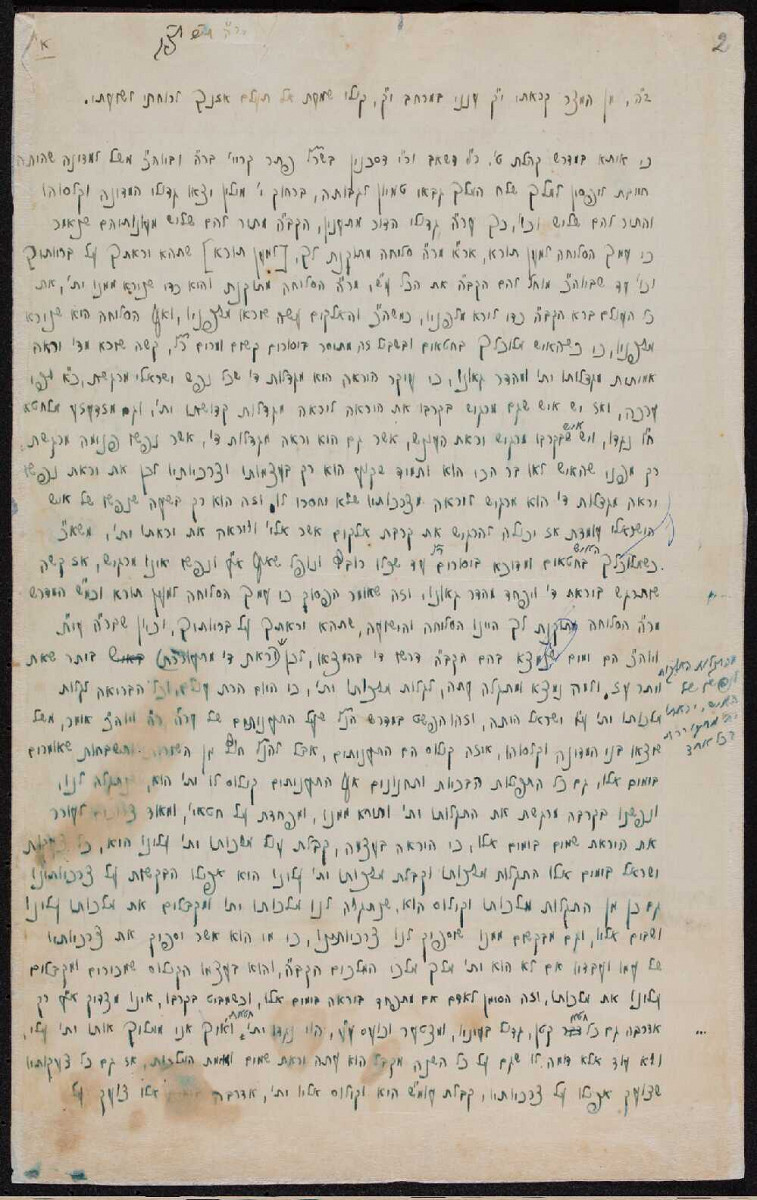

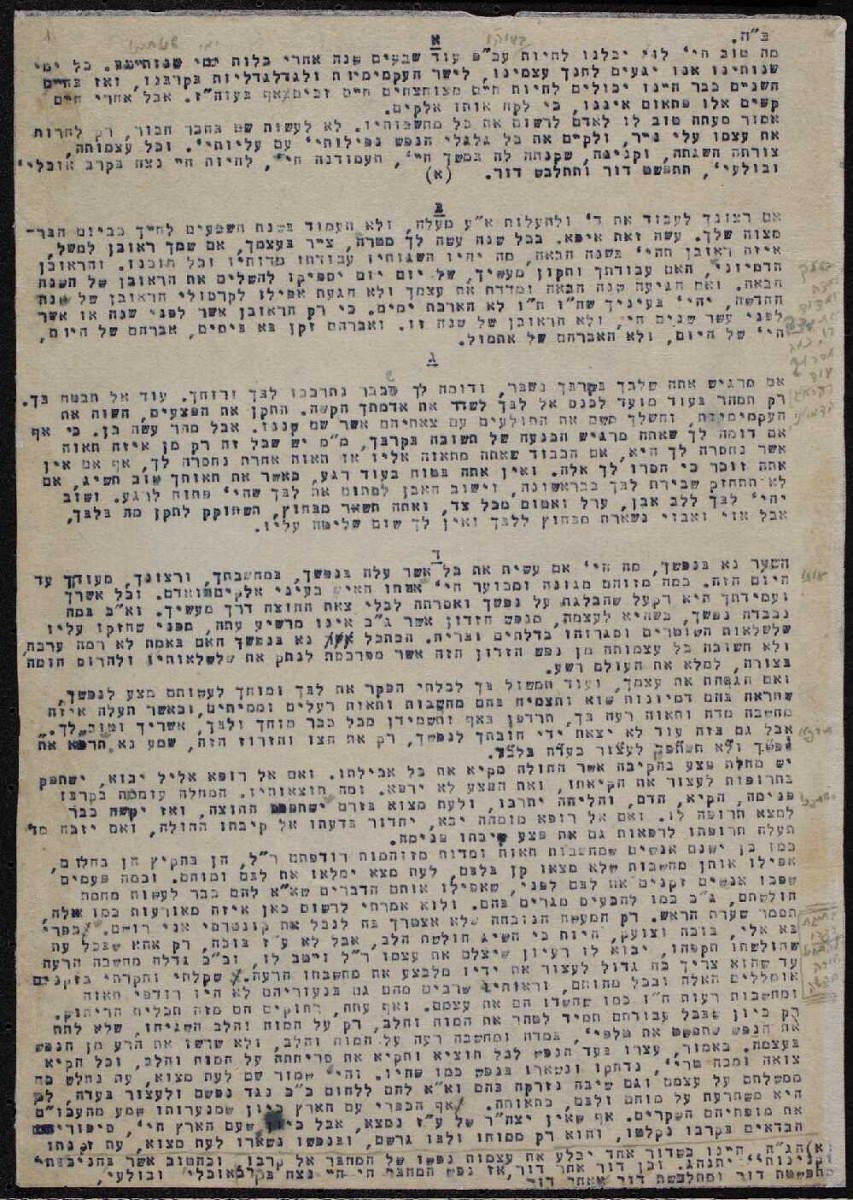

The Ringelblum Archive contains three manuscripts and one typescript by Shapiro: the manuscript of The Adept’s Manual, a continuation of the pre-war Chovas ha-talmidim, directed at older students (it was already finished before the war, only corrections were introduced during the occupation), An introduction to Hassidism (a continuation of The Adept’s Manual), as well as a manuscript of Shapiro’s sermons from September 1939 to July 1942. [11] They don’t relate directly to events in the ghetto, their role is to strengthen the faith of the listeners and the hope which allows for maintaining human dignity in the horrible ghetto conditions.

According to Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska,the value of these works is priceless – other documents collected by Oneg Shabbat give an image of reality of that period, but rabbi Shapiro’s sermons provide a testimony of spiritual life in the ghetto and changes taking place there. [12] It’s the only work completed fully after the beginning of the war; the last sermon was given on 18 July 1942, 4 days before the Great Deportation. [13]

The typescript contains his personal writings and theological reflections titled The Order and the Willing Fulfillment. He believed that it’s good to write down all thoughts – not in order to gain a writer’s fame, but to record oneself on paper, to save the wanderings of one’s soul, its highs and lows. [14]

The particularly moving fragments are related to the concerns about the health and life of his son, who had been suffering from gallstones for years, and many times was close to death. In the hospital, he wrote: This entire place and my whole existence have turned into one thought and one desire. My only son, the soul of my soul, threatened, judged, struggling, standing on a cliff above the sea, hanging between the world of the living and the abyss. (…) I’m sitting at the edge of his bed, scared and shivering. My heart feels squeezed, and my throat suffocates. [15]

The last fragment was written in September 1939, soon after the death of his son and his wife. I was bereft of all personal hope, mine and of my soul, which I have placed in them now and for the future. Also my future with them, when they would grow and move closer to heaven with their body, soul and spirit, was crushed (…) The sadness is unbearable. [16]

We don’t know much about his daily life during the occupation. We know that he belonged to the group of rabbis who wrote a prayer for people deported to Treblinka. Mentions about the rabbi appear in documents made by other Oneg Shabbat members, such as rabbi Szymon Huberbandd (his stepbrother), who participated in Shapiro’s weekly sermons, Emanuel Ringelblum or Emanuel Kohn, who, with high probability, donated Shapiro’s works to the Archive. [17]

Szymon Huberband wrote: After the ceremonial meal, I went to the rebbe of Piaseczno for tish. About 150 people have gathered there. The milky meal, like the one we eat every year, was not there. The tzaddik gave a commentary full of reinforcing words. Various songs were sang. After the tish, a traditional dance in procession began; the tzaddik was crying bitter tears. [18]

The Archive contains also a recollection from Kalman Huberband, The march to the mikveh, the beginning of the year 5701 [1940], where he described a visit to the mikveh organized by Shapiro despite the threat of a death sentence. [19]

On 18 July 1942, on the Shabbat before the Great Deportation, rabbi Shapiro gave his last sermon. We know that his daughter Rechil Ester was taken away to Treblinka. He was also arrested in a round-up, but he was freed and employed at a leather warehouse belonging to Schultz shoemaking workshop at 46 Nowolipie street.

In Spring 1943, he was deported to the labour camp in Trawniki. Jewish organizations were making efforts to free exceptional people from the camp, including rabbi Shapiro, but he declined, not wanting to leave his companions.

Samuel D. Kassow writes that he worked in the labout camp in Budzyń near Lublin, with Eliezer Lipe Bloch. Adolf Berman was trying to free Bloch in the same way he rescued Ringelblum from the Trawniki labour camp, sending a Polish railway worker, Teodor Pajewski, and his Jewish friend Emilka Kossower to free him secretly from the camp. But Bloch and 15 other Jews, including rabbi Shapiro, made an official vow that they will remain together, regardless of circumstances. [20]

Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapiro was murdered in early November – most likely November 3 – during the 'Aktion Erntefest' ('The feast of the crops'). He was shot together with other prisoners of the Trawniki camp.

A month later (exactly on 13 December 1943 r.) Emanuel Ringelblum, who remained in hiding in the „Krysia” bunker, wrote in a confidential message to Barbara and Adolf Berman, in which he reminded them about putting rabbi Kalman Shapiro on the list of scientists, writers, social activists and artists who had died or were killed: In the letter to Mr L., a person from the Trawniki company was missing and should be mentioned next time: Kielman Szapirski (well known in Piaseczno, a great, noble kind of man). [21] (translated by Olga Drenda)

Sources:

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, vol. 25, ed. Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, vol 29a, ed. Eleonora Bergman, Tadeusz Epsztein, Magdalena Siek, JHI, Warsaw 2018.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Szymona Huberbanda, vol. 32, ed. Anna Ciałowicz, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie, part I, vol 33, ed. Tadeusz Epsztein, Katarzyna Person, WUW, Warsaw 2016.

Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017.

Footnotes:

[1] Quote in the lead: Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, Introduction [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, vol. 25, ed. Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, JHI, Warsaw 2017, p. XVIII.

[2] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, vol. 25, ed. Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, JHI, Warsaw 2017, p. 2.

[3] Ibidem, p. 304.

[4] Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, Introduction [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, op. cit., p. XVII.

[5] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, op. cit., p. 7.

[6] Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, Introduction [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, op. cit., p. XX.

[7] Ibidem, p. XVIII.

[8] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, op. cit., p. 3.

[9] Everybody, including the first wife, were buried at the Jewish cemetery. Their matzevot were preserved in a good condition.

[10] Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, Introduction [in:] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, op. cit., p. XXIII.

[11] After the war, they were published as The Holy Fire (Hebr. Esh kodesh).

[12] Marta Dudzik-Rudkowska, Introduction [in:]Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, op. cit., p. XXIX.

[13] The sermons will be published in December 2020 by the JHI (ARG, vol. 25a, ed. Daniel Reiser, translated by Regina Gromacka)

[14] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Kalonimusa Kalmana Szapiry, op. cit., p. 267.

[15] Ibidem, p. 303.

[16] Ibidem, p. 307–308.

[17] It is likely that the incorporation of Szapira’s writings into the Archives was initiated by Rabbi Szymon Huberband.

[18] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma rabina Szymona Huberbanda, vol. 32, ed. Anna Ciałowicz, JHI, Warsaw 2017, p. 56.

[19] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Getto warszawskie, part I, vol. 33, ed. Tadeusz Epsztein, Katarzyna Person, WUW, Warsaw 2016, p. 240.

[20] Samuel D. Kassow, Who will write our history?, JHI, Warsaw 2017, p. 289–290.

[21] Archiwum Ringelbluma, Pisma Emanuela Ringelbluma z bunkra, op. cit., p. 282–283.