- News

- Events

- Oneg Shabbat

- Collections

- Research

- Exhibitions

- Education

- Publishing Department

- Genealogy

- About the Institute

- Bookstore

Students in front of the building of the Institute, Tłomackie Street (now "Solidarności" Alley), 1938 / JHI Collection

How was the Institute for Judaic Studies established?

Scientific knowledge about Judaism and Jewish culture – history, literature, philosophy and philology – was developing dynamically in the 19th century. Polish and Lithuanian Jews also participated in this process, but until the beginning of the 20th century, Polish lands lacked research and didactic institutions that would serve Judaic teachings, and not only rabbinic studies. [1]

Throughout the 19th century, Jewish communities in Poland made efforts to establish a modern Jewish university, educating in the spirit of the enlightened trend of Judaism, known as the Haskalah. Orthodox Jews saw no need for such activity, and even saw it as a threat to Jewish faith and identity. One of the main tasks of the Institute of Judaic Sciences, established in 1928, was to provide comprehensive training of rabbis in the Western European style and to stop the outflow of talented youth abroad. [2] Highly qualified staff for Jewish education throughout Poland was also needed.

In 1925, on the initiative of Professor Mojżesz Schorr, the Society for the Promotion of Judaic Sciences in Poland was established. Its task was to finance the activities of the planned educational institution. Jewish Senator in Polish Sejm, Markus Braude, obtained a pledge of government subsidies, and the B'nai B'rith Association was an important founder. The facility "serving the idea of the school, based on the synthesis of Jewish national culture and Polish statehood" was opened at the beginning of the summer semester of the 1928/1929 academic year. [3]

![Braude_senat.jpg [214.14 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/2/19/ab2ec478693054701e00f42fc9092faa/jpg/jhi/preview/Braude_senat.jpg)

To enrol at the Institute, one had to be a student at the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Warsaw (although students without high school diploma willing to study could participate in the classes as free students, there was also the possibility of extramural studies). The institution had two faculties – rabbinic and socio-historic – and the studies lasted four years. In order to take the final exams, a master's degree from the University of Warsaw was required. The Institute issued diplomas in two languages – Polish and Hebrew, and also issued rabbinical authorization in Hebrew. [4]

On February 19, 1928 at noon at Rymarska 8 Street (building no longer exists, today it’s Bankowy Square), the Institute's opening ceremony was held. It was attended by representatives of the government and city authorities, the rector of the University of Warsaw, members of the Jewish community and the Great Synagogue at Tłomackie, representatives of educational organizations and social institutions, as well as the first students. In the inaugural lecture, Professor Mojżesz Schorr expressed the hope that, in addition to education, the Institute would conduct research on the history and culture of Jews, devoted to issues such as Frankism, Hasidism, Haskalah, Jewish-Arab cultural relations and New Hebrew literature. [5]

Jakie były przedmioty wykładowe w Instytucie?

The institute included the following departments:

From the 1929/1930 academic year, the following subjects were taught:

"The Institute was the first university in Europe to fully incorporate, apart from theological sciences, secular Jewish sciences," [7] writes Henryk Kroszczor.

At that time, the staff consisted of nine associate professors and one assistant. The first rector, in the years 1928-1930, was Professor Schorr, his successor was Professor Bałaban (1930-1936), from 1937 the rector was Dr. Abraham Weiss.

The number of students increased from 28 in the 1928/1929 academic year to 83 in 1930/1931, and in 1935/1936 it was 73 people. The annual fee for studying was 100 zlotys, but students could be exempted from it "if they submit tests of 10 lecture hours per week". [8] This privilege was widely used. The Institute started paying monthly scholarships, but due to the Great Depression and the reduction of subsidies and contributions from associations, it had to discontinue this initiative in the 1930/1931 academic year – during that period, the Institute was maintained only by the Polish government. [9] This meant that a large proportion of students had to attend classes both at the University of Warsaw and at the Institute, and also had to earn their living.

Originally, the Institute was located in a school at 12 Leszno Street – the place was "rented unselfishly", [10] but available only in the afternoon. Already in 1928, the Institute moved to rented premises at 3 Nowolipie Street. Both spaces were too small for its needs. It was only in 1936, after the final finishing works in the building of the Main Judaic Library in Tłomackie, that the Great Synagogue Committee granted the Institute free use of the library rooms. [11] The Institute established its own reference library at the Main Judaic Library, and also used the Library’s extensive collections (about 36,600 volumes).

Many outstanding Jewish scientists and representatives of culture were among the lecturers. Apart from the main task of the Institute, which was teaching, no less emphasis was placed on scientific activity. One of its effects was the creation of the „Pismo Instytutu Nauk Judaistycznych w Warszawie” [Journal of the Institute for Judaic Studies in Warsaw]. During the 11 years of the Institute's operation, 10 volumes of the journal have been published. Unfortunately, due to the large number of works generated and low funds, not all works were published in print.

The facility was financed from several sources: the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Public Education, B'nai B'rith Humanitarian Associations, funds from the City of Warsaw and the Parisian Association "Alliance Israelite Universelle", as well as the Jewish communities of Warsaw and Lviv. The annual budget was around 30,000 zlotys, which quickly turned out to be insufficient. [12]

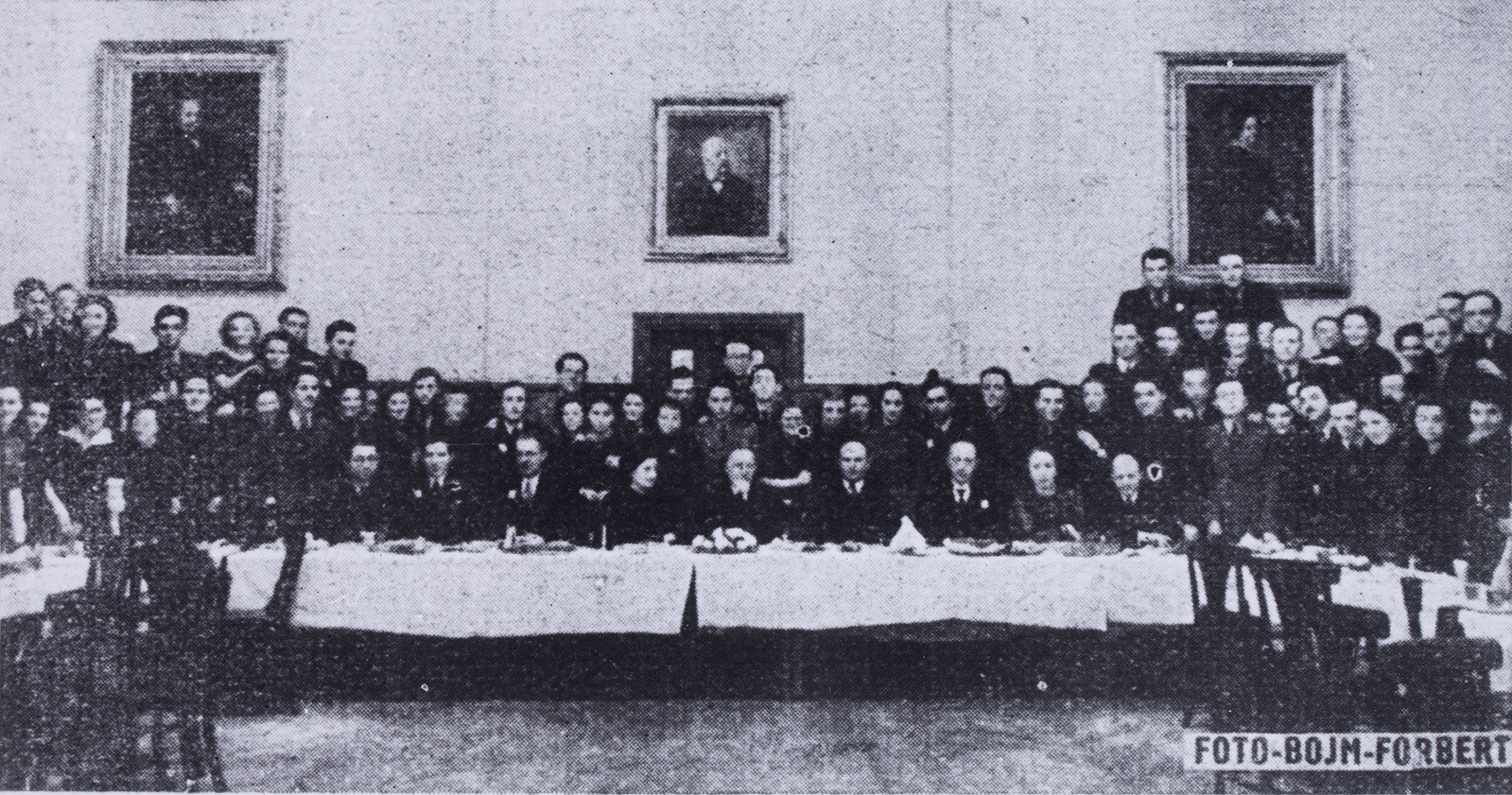

![INJ_zdj_3.jpg [290.67 KB]](https://www.jhi.pl/storage/image/core_files/2021/2/19/f319fdcab219bcbe6111d4b4db2532d7/jpg/jhi/preview/INJ_zdj_3.jpg)

"The lecturers with poor salaries, the students often hungry and in cold, linked by a common passion for Jewish science, expect to survive together and save the fragile primrose of Jewish science in Poland from destruction," wrote Izrael Ostersetzer, who conducted the Talmud exercises. He appealed to "the leaders of the Jewish society in Poland" for donations, as the Institute was supposed to "pierce from end to end the world’s largest Jewish center – the Poland Jewish community – with invigorating rays of science, national culture and self-knowledge”.[13]

Emanuel Ringelblum noted in the Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto: “It is worth recalling two facts: neither the Jewish language nor Jewish literature was taught at the institute; Bible criticism had no access to the thresholds of this reactionary establishment. Despite the religious and conservative nature of the Institute, it was the only college where young people could learn Judaic sciences”. [14] Ringelblum also criticized from the leftist standpoint historians such as Majer Bałaban, who did not include the perspective of class struggle in their works.

In 1939, with the outbreak of World War II, the Institute ceased its activity. By that time, it had educated about 100 Jewish teachers. The collections of the Main Judaic Library were stolen by the Germans. The building itself housed the Jewish Social Self-Help Center in the Warsaw Ghetto, and meetings of the underground group Oneg Szabat were also held there. In May 1943, the building was partially burnt down during the blowing up of the Great Synagogue in Tłomackie – the event considered the end of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. However, it survived the war as one of the few buildings in the ghetto area. Since 1947, the Jewish Historical Institute has been operating within its walls.

Footnotes:

[1] Henryk Kroszczor, Instytut Nauk Judaistycznych w Warszawie, „Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego” no 82, 1972, p. 27.

[2] Israel Ostersetzer, Instytut Nauk Judaistycznych w Warszawie, Warsaw 1931, p. 7.

[3] H. Kroszczor, op. cit., p. 31.

[4] Basic information about the Institute for Judaic Studies follows the article: Marian Fuks, Instytut Nauk Judaistycznych w Warszawie (1928-1939), in: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny – 50 lat działalności, Warsaw 1996, pp. 31-44. Cf: H. Kroszczor, op. cit., p. 32.

[5] Sprawozdanie Instytutu Nauk Judaistycznych w Warszawie za lata akademickie 1927/1928 – 1928/1929, Warsaw 1929, pp. XIX-XXI.

[6] Based on: I. Ostersetzer, op. cit., pp. 8-10.

[7] H. Kroszczor, op. cit., p. 31.

[8] I. Ostersetzer, op. cit., p. 11, spelling modernized.

[9] H. Kroszczor, op. cit., p. 30.

[10] Sprawozdanie…, op. cit., p. XXII.

[11] Ibid., p. 34.

[12] I. Ostersetzer, op. cit., p. 12.

[13] Ibid., s. 14.

[14] Emanuel Ringelblum, Kronika getta warszawskiego, introduction and ed. Artur Eisenbach, transl. Adam Rutkowski, Warsaw 1988, p. 557.